|

Switched reluctance motor

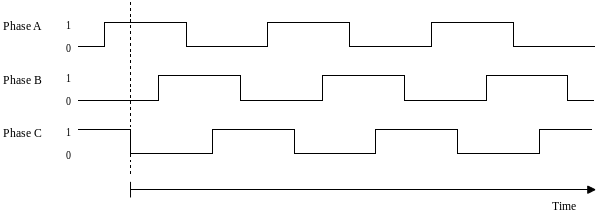

The switched reluctance motor (SRM) is a type of reluctance motor. Unlike brushed DC motors, power is delivered to windings in the stator (case) rather than the rotor. This simplifies mechanical design because power does not have to be delivered to the moving rotor, which eliminates the need for a commutator. However it complicates the electrical design, because a switching system must deliver power to the different windings and limit torque ripple.[1][2] Sources disagree on whether it is a type of stepper motor.[3] The simplest SRM has the lowest construction cost of any electric motor. Industrial motors may have some cost reduction due to the lack of rotor windings or permanent magnets. Common uses include applications where the rotor must remain stationary for long periods, and in potentially explosive environments such as mining, because no commutation is involved. The windings in an SRM are electrically isolated from each other, producing higher fault tolerance than induction motors. The optimal drive waveform is not a pure sinusoid, due to the non-linear torque relative to rotor displacement, and the windings' highly position-dependent inductance. HistoryThe first patent was by W. H. Taylor in 1838 in the United States.[4] The principles for SR drives were described around 1970,[5] and enhanced by Peter Lawrenson and others from 1980 onwards.[6] At the time, some experts viewed the technology as unfeasible,[7] and practical application has been limited, partly because of control issues and unsuitable applications, and because low production numbers result in higher cost.[8][1][9] Operating principleThe SRM has wound field coils as in a DC motor for the stator windings. The rotor however has no magnets or coils attached. It is a solid salient-pole rotor (having projecting magnetic poles) made of soft magnetic material, typically laminated steel. When power is applied to a stator winding, the rotor's magnetic reluctance creates a force that attempts to align a rotor pole with the nearest stator pole. In order to maintain rotation, an electronic control system switches on the windings of successive stator poles in sequence so that the magnetic field of the stator "leads" the rotor pole, pulling it forward. Rather than using a mechanical commutator to switch the winding current as in traditional motors, the switched-reluctance motor uses an electronic position sensor to determine the angle of the rotor shaft and solid state electronics to switch the stator windings, which enables dynamic control of pulse timing and shaping. This differs from the apparently similar induction motor which also energizes windings in a rotating phased sequence. In an SRM the rotor magnetization is fixed, meaning the salient 'North' poles remains so as the motor rotates. In contrast, an induction motor has slip, meaning it rotates at slower than the magnetic field in the stator. SRM's absence of slip makes it possible to know the rotor position exactly, allowing the motor to be stepped slowly, even to the point of being stopped completely. Simple switchingIf the poles A0 and A1 are energised then the rotor will align itself with these poles. Once this has occurred it is possible for the stator poles to be de-energised before the stator poles of B0 and B1 are energized. The rotor is now positioned at the stator poles b. This sequence continues through c before arriving back at the start. This sequence can also be reversed to achieve motion in the opposite direction. High loads and/or high de/acceleration can destabilize this sequence, causing a step to be missed, such that the rotor jumps to wrong angle, perhaps going back one step instead of forward three. QuadratureA much more stable system can be found by using a "quadrature" sequence in which up to two coils are energised at any time. First, stator poles A0 and A1 are energized. Then stator poles B0 and B1 are energized which, pulls the rotor so that it is aligned in between A and B. Following this A's stator poles are de-energized and the rotor continues on to be aligned with B. The sequence continues through BC, C and CA to complete a full rotation. This sequence can be reversed to achieve motion in the opposite direction. More steps between positions with identical magnetisation, so the onset of missed steps occurs at higher speeds or loads. In addition to more stable operation, this approach leads to a duty cycle of each phase of 1/2, rather than 1/3 as in the simpler sequence. ControlThe control system is responsible for giving the required sequential pulses to the power circuitry. It is possible to do this using electro-mechanical means such as commutators or analog or digital timing circuits. Many controllers incorporate programmable logic controllers (PLCs) rather than electromechanical components. A microcontroller can enable precise phase activation timing. It also enables a soft start function in software form, in order to reduce the amount of required hardware. A feedback loop enhances the control system.[1] Power circuitry The most common approach to powering an SRM is to use an asymmetric bridge converter. The switching frequency can be 10 times lower than for AC motors.[3] The phases in an asymmetric bridge converter correspond to the motor phases. If both of the power switches on either side of the phase are turned on, then that corresponding phase is actuated. Once the current has risen above the set value, the switch turns off. The energy now stored within the winding maintains the current in the same direction, the so-called back EMF (BEMF). This BEMF is fed back through the diodes to the capacitor for re-use, thus improving efficiency.[10]  This basic circuitry may be altered so that fewer components are required although the circuit performs the same action. This efficient circuit is known as the (n+1) switch and diode configuration. A capacitor, in either configuration, is used for storing BEMF for re-use and to suppress electrical and acoustic noise by limiting fluctuations in the supply voltage. If a phase is disconnected, an SR motor may continue to operate at lower torque, unlike an AC induction motor which turns off.[5][11] ApplicationsSRMs are used in some appliances,[12] in linear form for wave energy conversion,[13] magnetic levitation trains,[14] or industrial sewing machines.[15] The same electromechanical design can be used in a generator. The load is switched to the coils in sequence to synchronize the current flow with the rotation. Such generators can be run at much higher speeds than conventional types as the armature can be made as one piece of magnetisable material, as a slotted cylinder.[16] In this case the abbreviation SRM is extended to mean Switched Reluctance Machine, (along with SRG, Switched Reluctance Generator). A topology that is both motor and generator is useful for starting the prime mover, as it saves a dedicated starter motor. References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Switched reluctance machines.

|