|

Religion and drugs

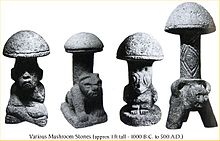

Many religions have expressed positions on what is acceptable to consume as a means of intoxication for spiritual, pleasure, or medicinal purposes. Psychoactive substances may also play a significant part in the development of religion and religious views as well as in rituals.[1][2][3][4][5] The most common drugs in the historical religions are cannabis and alcohol.[6][7] NeolithicIn the book Inside the Neolithic Mind, the authors, archaeologists David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce argue that hallucinogenic drugs formed the basis of neolithic religion and rock art. Ancient GreeceSome scholars have suggested that Ancient Greek mystery religions employed entheogens, such as the ergot-spiked Kykeon central to the Eleusinian Mysteries, which contained LSD-like compounds to induce a trance or dream state.[8] Research conducted by John R. Hale, Jelle Zeilinga de Boer, Jeffrey P. Chanton and Henry A. Spiller suggests that the prophecies of the Delphic Oracle were uttered by Priestesses under the influence of ethylene gas exuded from the ground.[9][10] Ancient Mesoamerica Archaeological, ethnohistorical, and ethnographic data show that Mesoamerican cultures used psychedelic substances in therapeutic and religious rituals.[11] The ancient Aztecs used a variety of entheogenic plants and animals within their society, including ololiuqui (Rivea corymbosa), teonanácatl (Psilocybe spp.), and peyotl (Lophophora williamsii).[12] Goals for the usage of entheogenics by the Maya were spiritual healing, wisdom gain, and religious ceremonies. The effects of psychedelic plants during religious rituals is believed to have had an impact on the development and creation of statues, and sacred images.[13] HinduismSomaHinduism has a history of psychedelic usage going back to the Vedic period. The oldest scriptures of Hinduism Rigveda (1500 BCE), mentions ritualistic consumption of a divine psychedelic known as soma. There are many theories about the recipe of Soma. Non-Indian researchers have proposed candidates including Amanita muscaria, Psilocybe cubensis, Peganum harmala and Ephedra sinica. According to recent philological and archaeological studies, and in addition, direct preparation instructions confirm in the Rig Vedic Hymns (Vedic period) Ancient Soma most likely consisted of poppy, Phaedra/Ephedra and Cannabis.[14][better source needed] In the Vedas, the same word soma is used for the drink, the plant, and its deity. Drinking soma produces immortality (Amrita, Rigveda 8.48.3). Indra and Agni are portrayed as consuming soma in copious quantities. In the vedic mythology, Indra drank large amounts of soma while fighting the serpent demon Vritra. The consumption of soma by human beings is well attested in Vedic ritual. The Rigveda (8.48.3) says:

Ralph T.H. Griffith translates this as:

CannabisThe plant Cannabis is also mentioned in the Atharvaveda-Samhita (1200 BCE) and Puranas (c. 200 BCE) as one of the ive of the holy plants. The Atharvaveda 11.6.15:

'भङ्ग' (bhang) refers to the cannabis plant. DaturaThe hallucinogenic Datura plant has also been used in Ayurvedic contexts and are often used to adorn the Lingam in many Shiva temples and festivals like Navarathri. The plant goes through a detoxification process to remove the psychoactive elements when utilized in standard Ayurveda practice. In the Vamana Purana, it is mentioned that the Datura flower appeared from the chest of Shiva and offering it the will remove evil, suffering and wrongdoings. There are also Sadhus who are worshipers of Shiva and sometimes smoke the leaves and seeds of Datura plant, though is done with caution because it can be poisonous and cause very vivid hallucinations (delirium). BuddhismIn Buddhism the Right View (samyag-dṛṣṭi / sammā-diṭṭhi) can also be translated as "right perspective", "right outlook" or "right understanding", is the right way of looking at life, nature, and the world as they really are for us. It is to understand how our reality works. It acts as the reasoning with which someone starts practicing the path. It explains the reasons for our human existence, suffering, sickness, aging, death, the existence of greed, hatred, and delusion. Right view gives direction and efficacy to the other seven path factors. It begins with concepts and propositional knowledge, but through the practice of right concentration, it gradually becomes transmuted into wisdom, which can eradicate the fetters of the mind. An understanding of right view will inspire the person to lead a virtuous life in line with right view. In the Pāli and Chinese canons, it is explained thus:[16][17][18][19][20] Right livelihoodRight livelihood (samyag-ājīva / sammā-ājīva). This means that practitioners ought not to engage in trades or occupations which, either directly or indirectly, result in harm for other living beings. In the Chinese and Pali Canon, it is explained thus:[16][18]

More concretely today interpretations include "work and career need to be integrated into life as a Buddhist,"[21] it is also an ethical livelihood, "wealth obtained through rightful means" (Bhikku Basnagoda Rahula) – that means being honest and ethical in business dealings, not to cheat, lie or steal.[22] As people are spending most of their time at work, it's important to assess how our work affects our mind and heart. So important questions include "How can work become meaningful? How can it be a support, not a hindrance, to spiritual practice a place to deepen our awareness and kindness?"[21] The five types of businesses that should not be undertaken:[23][24][25]

The fifth preceptAccording to the fifth precept of the Pancasila, Buddhists are meant to refrain from any quantity of "fermented or distilled beverages" which would prevent mindfulness or cause heedlessness.[26] In the Pali Tipitaka the precept is explicitly concerned with alcoholic beverages:

However, caffeine and tea are permitted, even encouraged for monks of most traditions, as it is believed to promote wakefulness. Generally speaking, the vast majority of Buddhists and Buddhist sects denounce and have historically frowned upon the use of any intoxicants by an individual who has taken the five precepts. Most Buddhists view the use and abuse of intoxicants to be a hindrance in the development of an enlightened mind. However, there are a few historical and doctrinal exceptions. VajrayanaMany modern Buddhist schools have strongly discouraged the use of psychoactive drugs of any kind; however, they may not be prohibited in all circumstances in all traditions. Some denominations of tantric or esoteric Buddhism especially exemplify the latter, often with the principle skillful means: AlcoholFor example, as part of the ganachakra tsok ritual (as well as Homa, abhisheka and sometimes drubchen) some Tibetan Buddhists and Bönpos have been known to ingest small amounts of grain alcohol (called amrit or amrita) as an offering. If a member is an alcoholic, or for some other reason does not wish to partake in the drinking of the alcoholic offering, then he or she may dip a finger in the alcohol and then flick it three times as part of the ceremony. Amrita is also possibly the same as, or at least in some sense a conceptual derivative of the ancient Hindu soma (the latter historians often equate with Amanita muscaria or other Amanita psychoactive fungi). Crowley (1996) states:

Conversely, in Tibetan and Sherpa lore there is a story about a monk who came across a woman who told him that he must either:

The monk thought to himself, "well, surely if I kill the goat then I will be causing great suffering since a living being will die. If I sleep with the woman then I will have broken another great vow of a monk and will surely be lost to the ways of the world. Lastly, if I drink the beer then perhaps no great harm will come and I will only be intoxicated for a while, and most importantly I will only be hurting myself." (In the context of the story this instance is of particular importance to him because monks in the Mahayana and Vajrayana try to bring all sentient beings to enlightenment as part of their goal.) So the monk drank the mug of beer and then he became very drunk. In his drunkenness he proceeded to kill the goat and sleep with the woman, breaking all three vows and, at least in his eyes, doing much harm in the world. The lesson of this story is meant to be that, at least according to the cultures from which it delineates, alcohol causes one to break all of one's vows, in a sense that one could say it is the cause of all other harmful deeds.[27] The Vajrayana teacher Drupon Thinley Ningpo Rinpoche has said that as part of the five precepts which a layperson takes upon taking refuge, that although they must refrain from taking intoxicants, they may drink enough so as they do not become drunk. Bhikkus and Bhikkunis (monks and nuns, respectively), on the other hand, who have taken the ten vows as part of taking refuge and becoming ordained, cannot imbibe any amount of alcohol or other drugs, other than pharmaceuticals taken as medicine. Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, is known as teetotaler and non-smoker. HallucinogensThere is some evidence regarding the use of deliriant Datura seeds (known as candabija) in Dharmic rituals associated with many tantras – namely the Vajramahabhairava, Samputa, Mahakala, Guhyasamaja, Tara and Krsnayamari tantras – as well as cannabis and other entheogens in minority Vajrayana sanghas.[28] Ronald M Davidson says that in Indian Vajrayana, Datura was:

In the Profound Summarizing Notes on the Path Presented as the Three Continua, a Sakya Lamdre text, by Jamyang Khyentse Wangchuk (1524–1568), the use of Datura in combination with other substances, is prescribed as part of a meditation practice meant to establish that "All the phenomena included in apparent existence, samsara and nirvana, are not established outside of one's mind."[30] Ian Baker writes that Tibetan terma literature such as the Vima Nyingtik describes "various concoctions of mind altering substances, including datura and oleander, which can be formed into pills or placed directly in the eyes to induce visions and illuminate hidden contents of the psyche."[31] A book titled Zig Zag Zen: Buddhism and Psychedelics (2002), details the history of Buddhism and the use of psychedelic drugs, and includes essays by modern Buddhist teachers on the topic. ZenZen Buddhism is known for stressing the precepts. In Japan, however, where Zen flourished historically, there are a number of examples of misconduct on the part of monks and laypeople alike. This often involved the use of alcohol, as sake drinking has and continues to be a well known aspect of Japanese culture. The Japanese Zen monk and abbot, shakuhachi player and poet Ikkyu was known for his unconventional take on Zen Buddhism: His style of expressing dharma is sometimes deemed "Red Thread Zen" or "Crazy Cloud Zen" for its unorthodox characteristics. Ikkyu is considered both a heretic and saint in the Rinzai Zen tradition, and was known for his derogatory poetry, open alcoholism and for frequenting the services of prostitutes in brothels. He personally found no conflict between his lifestyle and Buddhism. There are several koans (Zen riddles) referencing the drinking of sake (rice wine); for instance Mumonkan's tenth koan titled Seizei Is Utterly Destitute:

Another monk, Gudo, is mentioned in a koan called Finding a Diamond on a Muddy Road buying a gallon of sake. JudaismJudaism maintains that people do not own their bodies – they belong to God.[32] As a result, Jews are not permitted to harm, mutilate, destroy or take risks with their bodies, life or health with activities such as taking life-threatening drugs.[33] For these reasons, rabbis generally prohibit the use of drugs except in controlled medical situations.[34][35] Even without a risk to life or health, addictive drugs are discouraged due to their negative social effects.[36] When issues of physical, mental, and social harm are not present, it is debated whether drugs can have any positive spiritual value. According to Rabbi Walter Wurzburger, "Proximity to God cannot be reached by putting oneself into a trance either through physical or chemical means".[33] Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan suggested that some medieval kabbalists may have used some psychedelic drugs.[37] Indeed, one can find in Kabbalistic medical manuals cryptic references to the hidden powers of mandrake, harmal and other psychoactive plants, though the exact usage of these powers is hard to decipher. Some kabbalists, including Isaac of Acco and Abraham Abulafia, mention a method of "philosophical meditation", which involves drinking a cup of "strong wine of Avicenna", which would induce a trance and would help the adept to ponder over difficult philosophical questions.[38] The exact recipe of this wine remains unknown; Avicenna refers in his works to the effects of opium and datura extracts. According to Aryeh Kaplan, some have translated kaneh-bosem (קְנֵה-בֹשֶׂם), an ingredient in the holy anointing oil (Exodus 30:23), as cannabis.[39] However, the term kaneh-bosem literally translates to "sweet cane" (an association that is difficult to make with cannabis), and most lexicographers, botanists, and biblical commentators translate it as "calamus" (Acorus calamus),[40][41] a species known throughout the Middle East for its fragrance since the mid-2nd millennium BCE. Use of alcohol in moderation is an accepted part of Judaism. The Hebrew Bible states that "wine gladdens man's heart" (Psalms 104:15), and a single cup of wine is drunk for common rituals such as kiddush (though grape juice may be used instead).[34] Nevertheless, excessive use of alcohol is condemned. Prayer and priestly service are forbidden while intoxicated,[42] and numerous Biblical figures met their downfall through drunkenness.[43] The Talmud states that wine received its Hebrew name (whose sound somewhat resembles a howl) because it "brings lament to the world".[44] The holiday of Purim is exceptional in that on this date drunkenness is encouraged in some communities, in commemoration of the drunkenness which plays a significant role in the Book of Esther. In Hasidic Judaism alcohol consumption is more common, especially at communal religious events like the farbrengen or tisch, where alcohol often accompanies singing and Torah study. If the drinking is moderate, for the purpose of Divine service, and done together with other chassidim, it is considered useful for expanding the mind and providing enthusiasm in the service of God.[45] Nevertheless, excessive consumption is still discouraged; for example, the Lubavitcher Rebbe forbade his Chassidim under the age of 40 to consume more than 4 small shots of hard liqueurs.[33] The use of nicotine is well known in Hasidic communities. Stories are told about miracles and spiritual journeys performed by the Baal Shem Tov and other Tzaddikim with the help of their smoking pipe.[46] Hasidim valued smoking both as part of their general goal to raise the spiritual "sparks" that are allegedly present in base physical phenomena, and for the practical goal of experiencing better concentration while under its influence.[46] Nevertheless, since the health impacts of smoking have become understood by modern medicine, there has been a strong movement to discourage and prohibit smoking.[47] Caffeine use is accepted in Judaism, and played a significant role in the spread of nighttime rituals such as Tikkun Chatzot. Nevertheless, there was initially some opposition from rabbis who were concerned that nighttime gatherings or the coffeehouse atmosphere could lead to illicit behavior.[48] ChristianityMany Christian denominations disapprove of the use of most illicit drugs.[49] Many denominations permit the moderate use of socially and legally acceptable drugs like alcohol, caffeine and tobacco. Some Christian denominations permit smoking tobacco, while others disapprove of it. Many orthodox or protestant denominations do not have any official stance on drug use, while other Christian denominations (e.g. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Jehovah's Witnesses) discourage or prohibit the use of any of these substances. In the Eucharist, wine represents (or among Christians who believe in some form of Real Presence, like the Catholic, Lutheran and Orthodox churches, actually is) the blood of Christ. Lutherans believe in the real presence of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist,[50][51] that the body and blood of Christ are "truly and substantially present in, with and under the forms."[52][53] of the consecrated bread and wine (the elements), so that communicants orally eat and drink the holy body and blood of Christ Himself as well as the bread and wine (cf. Augsburg Confession, Article 10) in this Sacrament.[54][55] The Lutheran doctrine of the Real Presence is more accurately and formally known as "the Sacramental Union".[56] It has been inaccurately called "consubstantiation", a term which is specifically rejected by most Lutheran churches and theologians.[57] On the other hand, some Protestant Christian denominations, such as Baptists and Methodists associated with the temperance movement, encourage or require teetotalism, as well as abstinence from cultivating and using tobacco.[58] In some Protestant denominations, grape juice or non-alcoholic wine is used in place of wine in the administration of Holy Communion. Conservative Anabaptist denominations, such as the Dunkard Brethren Church, teach:[59]

The best-known Western prohibition against alcohol happened in the United States in the 1920s, where concerned prohibitionists were worried about its dangerous side effects. However, the demand for alcohol remained and criminals stepped in and created the supply. The consequences of organized crime and the popular demand for alcohol led to alcohol being legalized again. The Seventh-day Adventist Church is supportive of scientific medicine.[60] It promotes eradication of illicit drug use and promotes abstinence against tobacco and alcohol.,[61] and promotes a measured and balanced approach to use of both medicinal drugs as well as natural remedies (which it neither discourages or prohibits),[62] promotes the control of medicines that may be abused,[63] and promotes vaccination and immunization.[64] IslamAlcohol, or just wine (in the views of some), are considered haram but Nabith a drink that can ferment is halal if drank before it becomes fermented (permissable) The Muslim-majority nations of Turkey and Egypt were instrumental in banning opium, cocaine, and cannabis when the League of Nations committed to the 1925 International Convention relating to opium and other drugs (later the 1934 Dangerous Drugs Act). The primary goal was to ban opium and cocaine, but cannabis was added to the list, and it remained there largely unnoticed due to the much more heated debate over opium and cocaine. The 1925 Act has been the foundation upon which every subsequent policy in the United Nations has been founded. There are no prohibitions in Islam on alcohol for scientific, industrial or automotive use and cannabis is generally permitted for medicinal purposes.[65] In spite of these restrictions on substance use, the recreational use of cannabis still occurs widely throughout many Muslim nations. Baháʼí FaithFollowers of the Baháʼí Faith are forbidden to drink alcohol or to take drugs, unless prescribed by doctors. Accordingly, the sale and trafficking of such substances is also forbidden. Smoking is discouraged but not prohibited. Rastafari movementMany Rastafari believe cannabis, which they call "ganja", "the herb", or "Kaya", is a sacred gift of Jah. It may be used for spiritual purposes to commune with God, but should not be used profanely. The use of other drugs, however, including alcohol, is frowned upon. Many believe that the wine Jesus/Iyesus drank was not an alcoholic beverage, but simply the juice of grapes or other fruits. While some Rastafari suggest that the Hebrew Bible may refer to marijuana, it is generally held by academics specializing in the lexicography of the text that cannabis is not documented or mentioned. Some popular writers have argued that there is evidence for religious use of cannabis in the Hebrew Bible,[66] although this hypothesis and some of the specific case studies (e.g., John Allegro in relation to Qumran, 1970) have been "widely dismissed as erroneous" (Merlin, 2003).[67] The primary advocate of a religious use of cannabis plant in early Judaism was Sula Benet (1967), who claimed that the plant kaneh bosm קְנֵה-בֹשֶׂם mentioned five times in the Hebrew Bible, and used in the holy anointing oil of the Book of Exodus, was in fact cannabis,[68] although lexicons of Hebrew and dictionaries of plants of the Bible such as by Michael Zohary (1985), Hans Arne Jensen (2004) and James A. Duke (2010) and others identify the plant in question as either Acorus calamus or Cymbopogon citratus.[69] GroundationA "groundation" (also spelled "grounation") or "binghi" is a holy day; the name "binghi" is derived from "Nyabinghi" (literally "Nya" meaning "black" and "Binghi" meaning "victory"). Binghis are marked by much dancing, singing, feasting, and the smoking of "ganja", and can last for several days. Bible verses which Rastas believe justify cannabis use...thou shalt eat the herb of the field. Genesis 3.18 ...eat every herb of the land. Exodus 10:12 Better is a dinner of herb where love is, than a stalled ox and hatred therewith. Proverbs 15:17 Beliefs about other drugsAccording to many Rastas, the illegality of cannabis in many nations is evidence of persecution of Rastafari. They are not surprised that it is illegal, viewing Cannabis as a powerful substance that opens people's minds to the truth – something the Babylon system, they reason, clearly does not want. Cannabis use is contrasted with the use of alcohol and other drugs, which they feel destroy the mind. Native American religionThe Native American Church (NAC) is a syncretic Native American religion that teaches a combination of traditional Native American beliefs and elements of Christianity, with sacramental use of the entheogen peyote. It is the most widespread indigenous religion among Native Americans in the United States (except Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians), Canada (specifically First Nations people in Saskatchewan and Alberta), and Mexico, with an estimated 250,000 adherents as of the late twentieth century.[70] ThelemaAleister Crowley wrote The Gnostic Mass in 1913 while travelling in Moscow, Russia. The structure is similar to the Mass of the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church, communicating the principles of Crowley's Thelema. It is the central rite of Ordo Templi Orientis and its ecclesiastical arm, Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica.[71] The ceremony calls for five officers: a Priest, a Priestess, a Deacon, and two adult acolytes, called "the Children". The end of the ritual culminates in the consummation of the eucharist, consisting of a goblet of wine and a Cake of Light, after which the congregant proclaims "There is no part of me that is not of the gods!"[72] See also

References

Further reading

External links

|