|

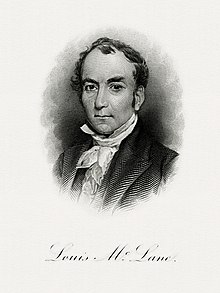

Louis McLane

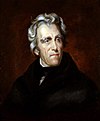

Louis McLane (May 28, 1786 – October 7, 1857) was an American lawyer and politician from Wilmington, in New Castle County, Delaware, and Baltimore, Maryland. He was a veteran of the War of 1812, a member of the Federalist Party and later the Democratic Party. He served as the U.S. representative from Delaware, U.S. senator from Delaware, the tenth U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, the twelfth U.S. Secretary of State, ambassador (Minister Plenipotentiary) to Great Britain, and president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. As a member of President Andrew Jackson's Cabinet, McLane was a prominent figure during the Bank War. McLane pursued a more moderate approach towards the Second Bank of the United States than the President, but agreed with Jackson's decision in 1832 to veto a Congressional bill renewing the Bank's charter. He also helped draft the Force Bill in 1833. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1831.[1] Early life and familyLouis McLane was born in Smyrna, Delaware, on May 28, 1786, to Allan McLane and Rebecca Wells McLane. McLane's father, was a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, appointed by George Washington in 1797 to the lucrative federal position of Customs collector for the Port of Wilmington. As a well-known and fervently loyal Federalist, he received the strong backing of James A. Bayard, enabling him to keep his appointment despite the election of a political opponent, Thomas Jefferson. Allan McLane retained the position for over 30 years, under presidents of both parties, until his death during the administration of Andrew Jackson. Much of his income came from the seizure of contraband. Louis McLane inherited much of this wealth, along with legal issues that lasted well beyond the death of his father. Louis married Catherine Mary (Kitty) Milligan in 1812. Their 13 children included Robert Milligan McLane (1815–1898), a governor of Maryland and U.S. ambassador; Louis McLane (1819–1905), who became a president of Wells Fargo & Co.; and Lydia Milligan Sims McLane (1822–1887), wife of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston.[2] Education and early careerLouis McLane attended private schools and served as a midshipman on the USS Philadelphia for one year before he turned 18. He then attended Newark College, later the University of Delaware. He studied law under James A. Bayard, and was admitted to the bar in 1807. He began a practice in Wilmington, Delaware. During the War of 1812, McLane joined the Wilmington Artillery Company, formed for the purpose of defending Wilmington. When Baltimore was threatened, they marched to its defense, but were sent back due to lack of provisions for them in Baltimore. Ultimately, they saw no action, and McLane left the unit with the rank of first lieutenant. Congressional serviceFollowing the War of 1812, Delaware was unique in continuing to have a viable Federalist Party. Never tainted by the secessionist activities of the New England Federalists and adaptive enough to institute modern electioneering practices, they held the loyalty of the majority Anglican/Methodist downstate population against the seemingly more radical Presbyterians and Irish immigrants in New Castle County. They remained the dominant political force in the state well into the 1820s, when the party finally disappeared, split between an allegiances to Andrew Jackson or to John Quincy Adams and the "American system" of Henry Clay and the Whigs. New Castle County manufacturers joined most of the old Federalist Party leadership in making the Whigs the new majority in the state. This included McLane's mentor, James A. Bayard and various members of the Clayton family, especially Thomas Clayton and his cousin, John M. Clayton. McLane was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives by defeating Thomas Clayton for the Federalist nomination, as Clayton was politically damaged by having voted for a Congressional pay raise in the previous session. From then on the Clayton cousins became McLane's principal political opponents in Delaware. Nevertheless, McLane was elected six times as a Federalist to the U.S. House of Representatives, from 1816 through 1826. He had a most distinguished career in the U.S. House, serving five full terms from March 4, 1817, to March 3, 1827. In spite being a Federalist, he was Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee and it was only his Federalist affiliation that prevented him from being elected Speaker. During these sessions the Federalist Party was so small and weak that partisan divisions mattered much less than the personal relationships that developed among the members. McLane quickly became a friend and admirer of William H. Crawford and Martin Van Buren, and at the same time became an opponent of Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams. These friendships were based more on personality than policy agreement, and were so important that McLane was one of Crawford's strongest proponents in the presidential election of 1824. Once Crawford returned to Georgia, McLane, Van Buren, and the other Crawford supporters fell into the party of Andrew Jackson. This was all the easier for him given his existing friendship with Martin Van Buren, who became his mentor and advocate. McLane moved to the U.S. Senate and served there from March 4, 1827, until his resignation in 1829, in expectation that President Jackson would appoint him to a federal office. During the period leading up to Andrew Jackson's victory in the presidential election of 1828, Senator McLane had worked very hard in an unsuccessful effort to win Delaware's electoral votes for Jackson. Service in the Jackson administrationHaving failed to win an appointment to Jackson's initial cabinet, as he had hoped, McLane nevertheless resigned from the Senate on April 29, 1829. In doing so, he completely cut his ties to the Claytons and the dominant political faction in the state. With little hope of reelection to the U.S. Senate or any future in Delaware politics, McLane counted on the new president to reward all of his considerable hopes with a prestigious position. However, a former Federalist from an inconsequential opposition state would have to wait until Jackson met other obligations. In October 1829, McLane reluctantly accepted an appointment as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the United Kingdom, which had been arranged by his friend Martin Van Buren, now U.S. Secretary of State. McLane was instructed to inform the English that his appointment signaled a break from the John Quincy Adams administration, and that issues of dispute under the Adams Administration would no longer be issues in a Jackson administration. His main assignment was to open up trade between the United States and the British West Indies. In this effort he was well received by Lord Aberdeen, the Foreign Secretary, and successfully accomplished his mission. During his tenure, his personal secretary was Washington Irving, who was thereafter a close and loyal family friend.[3]  Two years later, McLane finally received the cabinet appointment he had so longed for. When Jackson decided he needed to purge his cabinet of supporters of U.S. Senator John C. Calhoun, Van Buren was able to convince the president to appoint McLane to be the Secretary of the Treasury. McLane returned from England and served as Treasury Secretary from August 8, 1831, to May 28, 1833. The major issues confronting McLane in this new role were the tariff rates and the status of the Second Bank of the United States. When McLane entered Jackson's cabinet, he immediately assumed a position of leadership. Articulate, persuasive and energetic, he had mastered the issues under debate and was confident he could lead the others in the administration, including the President. Recognizing there was a difference of opinion with Jackson over the Bank, he sought to work out a plan with the bank president, Nicholas Biddle, to provide for the upcoming renewal of the bank's charter in return for the accomplishment of a key objective of the President, the retirement of the national debt. On December 7, 1831, he proposed a sweeping plan to accomplish that and more. Acclaimed for its Hamiltonian creativity, McLane had taken the initiative on the administration's agenda, and was acting very much in the role of a Prime Minister. With enough time he was certain Jackson would soften his position and consent to the approach. Events conspired to frustrate the plan, however. First of all, Attorney General Roger B. Taney sought to convince Jackson that McLane's plan was really a new packaging of the old Federalist program and in contradiction with Jackson's own past positions. At the time Jackson was somewhat flexible on the issue, and McLane wanted to postpone the decision until after the presidential election of 1832. But Henry Clay decided that renewal of the bank charter was an issue he could use to defeat Jackson and convinced bank president Biddle to press for an immediate re-charter. By itself, this crystallized Jackson's opposition to re-chartering, which he vetoed when passed by the Congress. This caused him to view his eventual victory in the presidential election as a popular endorsement of his bank policy. Liking McLane personally and unwilling to make more controversial Cabinet changes so quickly, Jackson removed the bank issue from McLane's purview. However, when McLane refused to remove the governments deposits from the Second Bank of the United States, Jackson had to replace him with someone that would, and offered McLane the prestigious U. S. Secretary of State instead. As his replacement, Jackson settled on William J. Duane, a man as unwilling as McLane to withdraw the deposits. The appointment was a great embarrassment to Jackson, and many blamed McLane for urging it. While all this was going on, McLane negotiated what seemed to be a satisfactory tariff bill, but when South Carolina continued to object and triggered the Nullification Crisis, McLane prepared the important Force Bill of 1833 to provide for the tariff's enforcement. By shuffling his cabinet, Jackson hoped to keep the talented McLane in his service by removing from him the obligation to implement his planned permanent destruction of the Second Bank of the United States. Appointed U.S. Secretary of State in a recess appointment, McLane served from May 29, 1833, until June 30, 1834. He quickly managed the first major reorganization of the department, by establishing seven new bureaus. He also managed a dispute with France, over what were known as the "Spoliation Claims". In 1832 France had agreed to reimburse the United States for certain shipping losses incurred during the Napoleonic Wars. However, successive French governments had failed to appropriate the funds required, all the while maintaining their desire to do so. Jackson was impatient to resolve the issue and worked with McLane to develop a hard line policy, confronting the French. Martin Van Buren was now Vice President and felt otherwise. Without consulting McLane, he intervened directly and convinced Jackson to give the French more time. McLane was furious with his old mentor for this intervention, and resigned his position, recognizing his apparent lack of authority in a direct area of responsibility. The incident also ended his friendship with Van Buren, and they never spoke again. Canal and railroad businessesAlthough he had some inherited wealth from his father, with 13 children McLane always needed to provide additional earned income in his own right. With his managerial talents, resume and connections, he was quickly sought out. The first to find him was the Morris Canal and Banking Company. A New Jersey corporation, largely based in New York City, it operated a canal from Phillipsburg to Newark, New Jersey, primarily to carry coal from Pennsylvania to New York City. It was also a bank and had a charter that provided banking opportunities. McLane was president for one year, implemented many improvements, and produced one of the few profitable years the company had. But his beloved family was in Wilmington and at their second home, "Bohemia," was in Cecil County, Maryland. New York City was too far away. Therefore, when an offer to assume the Presidency of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was made, it was quickly accepted. This company operated a railroad between Baltimore and Washington, but its ambition was built a route to the Ohio River, and move commerce from the west through the City of Baltimore. In 1837 the western tracks went only as far as Harpers Ferry, Virginia and McLane's great accomplishment was seeing to the extension of the "main line" as far as Cumberland, Maryland. This brought the route into proximity with enough coalfields to provide a regular profit. The profits were not substantial, however, and McLane was consumed with financing rearrangements and negotiations with Pennsylvania and Virginia over possible routes west. Ultimately Wheeling and an all Virginia route was decided upon, but it was left to McLane's immediate successor to see the goal realized. McLane never seemed to appreciate the value of this work and ultimately retired on September 13, 1848.[4] Further diplomatic service and the Oregon cessionIn spite of his political setbacks McLane never lost his ambition for high political office. One of his last remaining political friends from the congressional days was James K. Polk, who was now President of the United States. While he dreamed of something much greater, McLane took a leave of absence from the railroad in 1845 and 1846 to return to England as Minister Plenipotentiary, primarily for the purpose of coordinating negotiations over the Oregon boundary. McLane was remembered fondly from his previous service, and renewed his old friendships. The basis of the settlement was easily established, but the hard line public position of Polk was shaken only by outbreak of the Mexican–American War. McLane succeeded in keeping the British agreeable to the eventual settlement until the administration came to the same conclusion, even if he risked suggesting the president was posturing when he insisted on "54-40 or Fight." McLane never received the higher appointment desired and reluctantly returned to the railroad. Death and legacy The son of a Scots-Irish adventurer and politician from Delaware, McLane had married into the Eastern shore gentry of Maryland and ever longed for the idyllic plantation life seemingly promised. Acquiring Milligan Hall from his wife's family gave him a beautiful seat on the Bohemia River that became his favorite home. Called Bohemia, by the McLane family, it was always their gathering place and favorite retreat. Further, with his adherence to the party of Andrew Jackson and resignation from the United States Senate in 1829, McLane effectively admitted his political career in Delaware was over. So it was only natural for McLane to move his primary residence to Baltimore when he joined the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. He remained there after his retirement and entered the political life of his new home. Most notably he was an active participant in the Maryland constitutional convention of 1850. McLane died in Baltimore, Maryland and is buried in Green Mount Cemetery. McLane's biographer, Professor John A. Munroe, described him as follows:

He owned the Zachariah Ferris House, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.[6][7] His own house, the Louis McLane House, was listed in 1973.[7] Federal servicePublic offices

Congressional service and election returns

References

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||