|

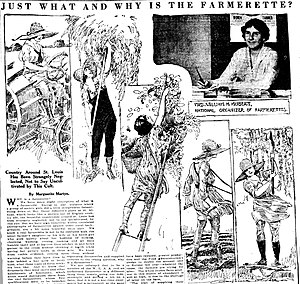

Woman's Land Army of America The Woman's Land Army of America (WLAA), later the Woman's Land Army (WLA), was a civilian organization created during the First and Second World Wars to work in agriculture replacing men called up to the military. Women who worked for the WLAA were sometimes known as farmerettes.[1] The WLAA was modeled on the British Women's Land Army.[2] World War I The Woman's Land Army of America (WLAA) operated from 1917 to 1919, organized in 42 states, and employing more than 20,000 women.[3][4] It was inspired by the women of Great Britain who had organized as the Women's Land Army, also known as the Land Girls or Land Lassies.[5] The women of the WLAA were known as 'farmerettes', a term derived from suffragettes and originally used pejoratively, but ultimately becoming positively associated with patriotism and women's war efforts. Many of the women of the WLAA were college educated, and units were associated with colleges.[6][7] Most of them had never worked on farms before.[4] The WLAA primarily consisted of college students, teachers, secretaries, and those with seasonal jobs or occupations which allowed summer vacation. They were paid equally with male farm laborers and had an eight-hour workday.[4] The WLAA workers eventually became wartime icons, much as Rosie the Riveter would in World War Two.[4]  In 1917, Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, became the director of the WLAA.[8] White, middle-upper class married women held administrative positions within the WLAA.[8] Fourteen women served as the WLAA's board of directors.[8] The president of the board of directors was Mrs. William H. Schofield.[8] The board of directors of the WLAA sought to establish labor and living standards for WLAA workers through a unit system consisting of Community Units, Single Farm Units, and Individual Units.[8] The number of women per Community Unit varied anywhere from 4 to 70 workers, who lived in a communal camp but were employed on different surrounding farms. Single Farm Units composed of women workers all employed on the same local farm. Both Community and Single Farm Units had their own captain to oversee daily productivity and management. Individual Units were less common, and they consisted of a single women worker employed on a local farm. The WLAA operated on regional and state-levels. WLAA land units were more prevalent on the West and East Coasts than in the Mid-West or Southern regions. Due to prejudice and sexism against women in agricultural work, many Mid-Western and Southern farmers and communities rejected help from the WLAA. However, by 1918, 15,000 women across twenty states had participated in agricultural training and education programs.[8] California, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Maryland, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Virginia[8] offered training for agricultural work. In Bedford, New York, Mrs. Charles W. Short Jr. established the Women's Agricultural Camp to offer farm training and employment beginning on June 4, 1918.[9] The Camp provided female farm labor to not only farmers, but to estates, home, and public gardens.[9] A uniform of brimmed hats, gloves, men's overalls, and a blue work shirt was provided and required.[9] Bedford's Women's Agricultural Camp is credited with proving the efficiency of the unit system. The WLAA did not receive government funding or assistance. Instead, the WLAA functioned with the help of non-profit organization, universities, colleges.[8] Often, universities and colleges initiated, led, and promoted their own WLAA land unit. Professor Ida H. Ogilvie and Professor Delia W. Marble of Barnard College established and ran an agricultural training program on their 680-acre farmland.[8] Vassar College's 740-acre farm provided land for students to cultivate and to train on. Vassar student farm workers earned 17 and a half cents an hour and worked an eight-hour day.[9] Additionally, Wellesley College, Blackburn College, Massachusetts Agricultural College, Pennsylvania State College, and the University of Virginia offered agricultural training and educational courses.[8] In February 1918, The Woman's Land Army of America published a second edition of Help for the Farmer. The pamphlet aimed to answer common questions farmers had about employing women farm laborers. In addition, Help for the Farmer offered a list of the agricultural skills women could do: "Ploughing…Cultivating, Thinning, Weeding, Hoeing, Potato planting, Fruit picking, assorting, and packing for market, Mowing, both with scythe and mowing machine, [and] Hay raking and pitching".[10] While employed on farms, women also completed dairy work. The WLAA was supported by progressives like Theodore Roosevelt, and was strongest in the West and Northeast, where it was associated with the suffrage movement. Other groups helping to organize the WLAA included the Woman's National Farm and Garden Association (WNFGA), the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women, the State Council of Defense of some states, the Garden Club of America, and the YMCA. In addition to the WLAA, the U.S. government sponsored the U.S. School Garden Army and the National War Garden Commission. Opposition came from Nativists, opponents of President Woodrow Wilson, and those who questioned the women's strength and the effect on their health.[7] Due to lack of government funding and support post-World War I, the WLA dissolved in 1920.[8] World War IIThe Women's Land Army (WLA) was formed as part of the United States Crop Corps, alongside the Victory Farm Volunteers (for teenage boys and girls), and lasted from 1943 to 1947.[11][12][13] In the five years the WLA operated, the program employed nearly 3.5 million workers, which included both farm laborers[14] and non-laborers. Before the Women's Land Army (WLA) founding in 1943, states such as Connecticut, Vermont, California, and New York had already employed women's farm labor in 1941 and 1942 out of immediate necessity.[14] Such local initiatives provided successful examples and motivation for the United States government to establish federal labor programs, like the WLA.[14] Beginning in 1940, the United States faced a severe shortage of agricultural labor. By the end of 1942, an estimated two million male workers had left the farms.[14][15] In total, by 1945, six million farm workers had left the farms to enlist and join the war effort.[14] Though the United States Department of Agriculture and the Women's Bureau proposed the Women's Land Army in 1941, Congress did not formally approve the WLA until 1943.[14] The Women's Bureau advocated for female farm employment, a wage of thirty cents per hour, physical ability requirement, and standard housing conditions.[14] The Women's Bureau treated urban women workers as a last resort and preferred local and rural women workers, who could immediately help their local farms. Women who were hired from the WLA did not work much in the fields but assisted the wives of farmers in their daily chores.[16] Town women that helped on farms were seen as too green and generally not wanted for agricultural labor.[16] In 1942, The United States Department of Agriculture further considered farm labor programs which included both woman and urban labor. The Department of Agriculture officially proposed in 1943 a national agricultural labor program, which included provisions for establishment of the Women's Land Army.[14] The WLA was allotted $150,000 for its first year of operation. Florence Hall was appointed as the head of the Women's Land Army.[14] Though federally funded, the WLA operated on state and local levels, rather than through the national organization. State and local WLA organizations recruited and placed women on farms, while the national WLA organization produced promotions, conferences, and propaganda encouraging women to become farmerettes. In 1943, the WLA gained 600,000 women workers, 250,000 of whom who had relied on local WLA units and administration for employment.[14] The goal was to recruit as many women and girls as possible. In 1943, Florence Hall had secured WLA agents in 43 of the 50 states.[15] California employed nearly 28,000; New York employed 6,000; Mississippi employed 43,000; Oregon employed more than 15,00, and Texas employed 75,000.[14] States such as Iowa and Minnesota remained hostile to women working on farms.[14] Similar to the training women received during the Woman's Land Army of America, women of the Woman's Land Army gained skills through agricultural college or farm-led programs. Nine of the 43 states offered special programs. Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science offered a 25-day intensive course on milking, egg grading, food packing, maintaining horses, and operating machinery.[15] The majority of WLA workers were seasonal labor consisting of White urban students, soldier's spouses, clerks, teachers, secretaries and other office workers. A uniform of denim overalls, a blue shirt, blue jacket, and a cap was encouraged, but not required.[14] Women could purchase the uniform or wear their own work clothing, thus uniforms varied from state to state. Women were paid an unskilled worker's wage, ranging from 25 to 50 cents per hour.[15] To save on costs, which included paying for their own meals,[17] many lived at home and commuted to their farm jobs.[15] However, women from distant urban areas lived in communal camps or buildings near their farm. Working in shifts allowed women to maintain their primary occupations. Other emergency farm worker programs in the U.S. included the Bracero Program (1942–1947), an agreement with Mexico. See also

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Woman's Land Army of America. |