|

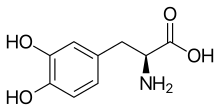

Levodopa

Levodopa, also known as L-DOPA and sold under many brand names, is a dopaminergic medication which is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and certain other conditions like dopamine-responsive dystonia and restless legs syndrome.[3] The drug is usually used and formulated in combination with a peripherally selective aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD) inhibitor like carbidopa or benserazide.[3] Levodopa is taken by mouth, by inhalation, through an intestinal tube, or by administration into fat (as foslevodopa).[3] Side effects of levodopa include nausea, the wearing-off phenomenon, dopamine dysregulation syndrome, and levodopa-induced dyskinesia, among others.[3] The drug is a centrally permeable monoamine precursor and prodrug of dopamine and hence acts as a dopamine receptor agonist.[3] Chemically, levodopa is an amino acid, a phenethylamine, and a catecholamine.[3] Levodopa was first synthesized and isolated in the early 1910s.[3] The antiparkinsonian effects of levodopa were discovered in the 1950s and 1960s.[3] Following this, it was introduced for the treatment of Parkinson's disease in 1970.[3] Medical usesLevodopa crosses the protective blood–brain barrier, whereas dopamine itself cannot.[3][4] Thus, levodopa is used to increase dopamine concentrations in the treatment of Parkinson's disease, Parkinsonism, dopamine-responsive dystonia and Parkinson-plus syndrome. The therapeutic efficacy is different for different kinds of symptoms. Bradykinesia and rigidity are the most responsive symptoms while tremors are less responsive to levodopa therapy. Speech, swallowing disorders, postural instability, and freezing gait are the least responsive symptoms.[5] Once levodopa has entered the central nervous system, it is converted into dopamine by the enzyme aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD), also known as DOPA decarboxylase (DDC). Pyridoxal phosphate (vitamin B6) is a required cofactor in this reaction, and may occasionally be administered along with levodopa, usually in the form of pyridoxine. Because levodopa bypasses the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting step in dopamine synthesis, it is much more readily converted to dopamine than tyrosine, which is normally the natural precursor for dopamine production. In humans, conversion of levodopa to dopamine does not only occur within the central nervous system. Cells in the peripheral nervous system perform the same task. Thus administering levodopa alone will lead to increased dopamine signaling in the periphery as well. Excessive peripheral dopamine signaling is undesirable as it causes many of the adverse side effects seen with sole levodopa administration. To bypass these effects, it is standard clinical practice to coadminister (with levodopa) a peripheral DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (DDCI) such as carbidopa (medicines containing carbidopa, either alone or in combination with levodopa, are branded as Lodosyn[6] (Aton Pharma)[7] Sinemet (Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited), Pharmacopa (Jazz Pharmaceuticals), Atamet (UCB), Syndopa and Stalevo (Orion Corporation) or with a benserazide (combination medicines are branded Madopar or Prolopa), to prevent the peripheral synthesis of dopamine from levodopa). However, when consumed as a botanical extract, for example from M pruriens supplements, a peripheral DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor is not present.[8] Inbrija (previously known as CVT-301) is an inhaled powder formulation of levodopa indicated for the intermittent treatment of "off episodes" in patients with Parkinson's disease currently taking carbidopa/levodopa.[9] It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration on 21 December 2018, and is marketed by Acorda Therapeutics.[10] Coadministration of pyridoxine without a DDCI accelerates the peripheral decarboxylation of levodopa to such an extent that it negates the effects of levodopa administration, a phenomenon that historically caused great confusion. In addition, levodopa, co-administered with a peripheral DDCI, is efficacious for the short-term treatment of restless leg syndrome.[11] The two types of response seen with administration of levodopa are:

Available formsLevodopa is available, alone and/or in combination with carbidopa, in the form of immediate-release oral tablets and capsules, extended-release oral tablets and capsules, orally disintegrating tablets, as a powder for inhalation, and as an enteral suspension or gel (via intestinal tube).[12][13] In terms of combination formulations, it is available with carbidopa (as levodopa/carbidopa), with benserazide (as levodopa/benserazide), and with both carbidopa and entacapone (as levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone).[12][13][14][15] In addition to levodopa itself, certain prodrugs of levodopa are available, including melevodopa (melevodopa/carbidopa) (used orally) and foslevodopa (foslevodopa/foscarbidopa) (used subcutaneously).[16][17][18] Side effectsThe side effects of levodopa may include:

Although many adverse effects are associated with levodopa, in particular psychiatric ones, it has fewer than other antiparkinsonian agents, such as anticholinergics and dopamine receptor agonists. More serious are the effects of chronic levodopa administration in the treatment of Parkinson's disease, which include:

Rapidly decreasing the dose of levodopa can result in neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Clinicians try to avoid these side effects and adverse reactions by limiting levodopa doses as much as possible until absolutely necessary. Metabolites of dopamine, such as DOPAL, are known to be dopaminergic neurotoxins. The long term use of levodopa increases oxidative stress through monoamine oxidase led enzymatic degradation of synthesized dopamine causing neuronal damage and cytotoxicity. The oxidative stress is caused by the formation of reactive oxygen species (H2O2) during the monoamine oxidase led metabolism of dopamine. It is further perpetuated by the richness of Fe2+ ions in striatum via the Fenton reaction and intracellular autooxidation. The increased oxidation can potentially cause mutations in DNA due to the formation of 8-oxoguanine, which is capable of pairing with adenosine during mitosis.[20] See also the catecholaldehyde hypothesis. PharmacologyPharmacodynamicsLevodopa is a dopamine precursor and prodrug of dopamine and hence acts as a non-selective dopamine receptor agonist, including of the D1-like receptors (D1, D5) and the D2-like receptors (D2, D3, D4).[3] PharmacokineticsThe bioavailability of levodopa is 30%.[3] It is metabolized into dopamine by aromatic-l-amino-acid decarboxylase (AAAD) in the central nervous system and periphery.[3] The elimination half-life of levodopa is 0.75 to 1.5 hours.[3] It is excreted 70 to 80% in urine. ChemistryLevodopa is an amino acid and a substituted phenethylamine and catecholamine.[3] Analogues and prodrugs of levodopa include melevodopa, etilevodopa, foslevodopa, and XP-21279. Some of these, like melevodopa and foslevodopa, are approved for the treatment of Parkinson's disease similarly to levodopa. Other analogues include methyldopa, an antihypertensive agent, and droxidopa (L-DOPS), a norepinephrine precursor and prodrug. 6-Hydroxydopa, a prodrug of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), is a potent dopaminergic neurotoxin used in scientific research. HistoryLevodopa was first synthesized in 1911 by Torquato Torquati from the Vicia faba bean.[3] It was first isolated in 1913 by Marcus Guggenheim from the V. faba bean.[3] Guggenheim tried levodopa at a dose of 2.5 mg and thought that it was inactive aside from nausea and vomiting.[3] In work that earned him a Nobel Prize in 2000, Swedish scientist Arvid Carlsson first showed in the 1950s that administering levodopa to animals with drug-induced (reserpine) Parkinsonian symptoms caused a reduction in the intensity of the animals' symptoms. In 1960 or 1961 Oleh Hornykiewicz, after discovering greatly reduced levels of dopamine in autopsied brains of patients with Parkinson's disease,[3][21] published together with the neurologist Walther Birkmayer dramatic therapeutic antiparkinson effects of intravenously administered levodopa in patients.[22] This treatment was later extended to manganese poisoning and later Parkinsonism by George Cotzias and his coworkers,[23] who used greatly increased oral doses, for which they won the 1969 Lasker Prize.[24][25] The first study reporting improvements in patients with Parkinson's disease resulting from treatment with levodopa was published in 1968.[26] Levodopa was first marketed in 1970 by Roche under the brand name Larodopa.[3] The neurologist Oliver Sacks describes this treatment in human patients with encephalitis lethargica in his 1973 book Awakenings, upon which the 1990 movie of the same name is based. Carbidopa was added to levodopa in 1974 and this improved its tolerability.[3] Society and cultureNamesLevodopa is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCF, DCIT, and JAN.[27][28][14][15] ResearchNovel formulations and prodrugsNew levodopa formulations for use by other routes of administration, such as subcutaneous administration, are being developed.[29][30] Levodopa prodrugs, with the potential for better pharmacokinetics, reduced fluctuations in levodopa levels, and reduced "on–off" phenomenon, are being researched and developed.[31][32] DepressionLevodopa has been reported to be inconsistently effective as an antidepressant in the treatment of depressive disorders.[33][34] However, it was found to enhance psychomotor activation in people with depression.[33][34] Motivational disordersLevodopa has been found to increase the willingness to exert effort for rewards in humans and hence appears to show pro-motivational effects.[35][36] Other dopaminergic agents have also shown pro-motivational effects and may be useful in the treatment of motivational disorders.[37] Age-related macular degenerationIn 2015, a retrospective analysis comparing the incidence of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) between patients taking versus not taking levodopa found that the drug delayed onset of AMD by around 8 years. The authors state that significant effects were obtained for both dry and wet AMD.[38][non-primary source needed] References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||