|

An Essay on the Principle of Population

The book An Essay on the Principle of Population was first published anonymously in 1798,[1] but the author was soon identified as Thomas Robert Malthus. The book warned of future difficulties, on an interpretation of the population increasing in geometric progression (so as to double every 25 years)[2] while food production increased in an arithmetic progression, which would leave a difference resulting in the want of food and famine, unless birth rates decreased.[2] While it was not the first book on population, Malthus's book fuelled debate about the size of the population in Britain and contributed to the passing of the Census Act 1800. This Act enabled the holding of a national census in England, Wales and Scotland, starting in 1801 and continuing every ten years to the present. The book's 6th edition (1826) was independently cited as a key influence by both Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace in developing the theory of natural selection. A key portion of the book was dedicated to what is now known as the Malthusian Law of Population. The theory claims that growing population rates contribute to a rising supply of labour and inevitably lowers wages. In essence, Malthus feared that continued population growth lends itself to poverty. In 1803, Malthus published, under the same title, a heavily revised second edition of his work.[3] His final version, the 6th edition, was published in 1826. In 1830, 32 years after the first edition, Malthus published a condensed version entitled A Summary View on the Principle of Population, which included responses to criticisms of the larger work. OverviewBetween 1798 and 1826 Malthus published six editions of his famous treatise, updating each edition to incorporate new material, to address criticism, and to convey changes in his own perspectives on the subject. He wrote the original text in reaction to the optimism of his father and his father's associates (notably Rousseau) regarding the future improvement of society. Malthus also constructed his case as a specific response to writings of William Godwin (1756–1836) and of the Marquis de Condorcet (1743–1794).  Malthus regarded ideals of future improvement in the lot of humanity with scepticism, considering that throughout history a segment of every human population seemed relegated to poverty. He explained this phenomenon by arguing that population growth generally expanded in times and in regions of plenty until a relatively large size of population, relative to a more modest supply of primary resources, caused distress:

Malthus also saw that societies through history had experienced at one time or another epidemics, famines, or wars: events that masked the fundamental problem of populations overstretching their resource limitations:

The rapid increase in the global population of the past century exemplifies Malthus's predicted population patterns; it also appears to describe socio-demographic dynamics of complex pre-industrial societies. These findings are the basis for neo-Malthusian modern mathematical models of long-term historical dynamics.[5] Proposed solutionsMalthus argued that two types of checks hold population within resource limits: The first, or preventive check to lower birth rates and The second, or positive check to permit higher mortality rates. This second check "represses an increase which is already begun" but by being "confined chiefly, though not perhaps solely, to the lowest orders of society". The preventive checks could involve birth control, postponement of marriage, and celibacy while the positive checks could involve hunger, disease and war.[6] Malthus highlighted the difference between governmentally instituted welfare and privately supported benevolence and proposed a gradual abolition of poor laws which he thought would be accompanied by a mitigation of the circumstances within which people would need relief and by privately supported benevolence supporting those in distress.[7] He reasoned that poor relief acted against the longer-term interests of the poor by raising the price of commodities and undermining the independence and resilience of the peasant.[citation needed] In other words, the poor laws tended to "create the poor which they maintain."[8] It offended Malthus that critics claimed he lacked a caring attitude toward the situation of the poor. In the 1798 edition his concern for the poor shows in passages such as the following:

In an addition to the 1817 edition he wrote:

Some, such as William Farr[10] and Karl Marx,[11] argued that Malthus did not fully recognize the human capacity to increase food supply. On this subject, however, Malthus had written: "The main peculiarity which distinguishes man from other animals, in the means of his support, is the power which he possesses of very greatly increasing these means."[12] He also commented on the notion that Francis Galton later called eugenics:

On religionAs a Christian and a clergyman, Malthus addressed the question of how an omnipotent and caring God could permit suffering. In the First Edition of his Essay (1798) Malthus reasoned that the constant threat of poverty and starvation served to teach the virtues of hard work and virtuous behaviour.[13] "Had population and food increased in the same ratio, it is probable that man might never have emerged from the savage state,"[14] he wrote, adding further, "Evil exists in the world not to create despair, but activity."[15] Similarly, Malthus believed that "the infinite variety of nature...is admirably adapted to further the high purpose of the creation and to produce the greatest possible quantity of good."[16] Nevertheless, although the threat of poverty could be understood to be a prod to motivate human industry, it was not God's will that man should suffer. Malthus wrote that mankind itself was solely to blame for human suffering:

Theory of MindMalthus referred to the last two chapters of the Essay (1798) as his "theory of mind".[19] These chapters contain a sophisticated - and heterodox - theory of mind, in which Malthus advocated for a naturalized conception of humans and mind.[20] For Malthus mind arose out of matter and he emphasized this throughout the Essay, employing the phrases "matter into mind" and "mind out of matter" throughout.[21] Bodily sensations power the whole mental apparatus, compelling the body into action:

Malthus's theory of mind, therefore, posited that "matter is formed into mind by the impressions and stimulations of nature upon the body and the ensuing perpetual struggle to avoid pain and pleasure".[20] This naturalized conception of mind was omitted from all subsequent editions which was most likely due to the fact that Malthus's theory of mind was singled out for critique. Demographics, wages, and inflationMalthus wrote of the relationship between population, real wages, and inflation. When the population of laborers grows faster than the production of food, real wages fall because the growing population causes the cost of living (i.e., the cost of food) to go up. Difficulties of raising a family eventually reduce the rate of population growth, until the falling population again leads to higher real wages:

In later editions of his essay, Malthus clarified his view that if society relied on human misery to limit population growth, then sources of misery (e.g., hunger, disease, and war, termed by Malthus "positive checks on population") would inevitably afflict society, as would volatile economic cycles. On the other hand, "preventive checks" to population that limited birthrates, such as later marriages, could ensure a higher standard of living for all, while also increasing economic stability.[24] Editions and versions

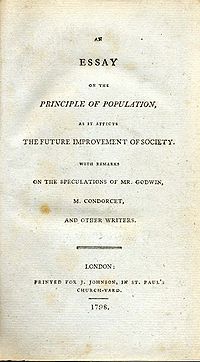

1st editionThe full title of the first edition of Malthus' essay was "An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the Future Improvement of Society with remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers." The speculations and other writers are explained below. William Godwin had published his utopian work Enquiry concerning Political Justice in 1793, with later editions in 1796 and 1798. Also, Of Avarice and Profusion (1797). Malthus' remarks on Godwin's work spans chapters 10 through 15 (inclusive) out of nineteen. Godwin responded with Of Population (1820). The Marquis de Condorcet had published his utopian vision of social progress and the perfectibility of man Esquisse d'un Tableau Historique des Progres de l'Espirit Humain (Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind) in 1794. Malthus' remarks on Condorcet's work spans chapters 8 and 9. Malthus' essay was in response to these utopian visions, as he argued:

The "other writers" included Robert Wallace, Adam Smith, Richard Price, and David Hume. Malthus himself claimed:

Chapters 1 and 2 outline Malthus' Principle of Population, and the unequal nature of food supply to population growth. The exponential nature of population growth is today known as the Malthusian growth model. This aspect of Malthus' Principle of Population, together with his assertion that food supply was subject to a linear growth model, would remain unchanged in future editions of his essay. Note that Malthus actually used the terms geometric and arithmetic, respectively. Chapter 3 examines the overrun of the Roman empire by barbarians, due to population pressure. War as a check on population is examined. Chapter 4 examines the current state of populousness of civilized nations (particularly Europe). Malthus criticises David Hume for a "probable error" in his "criteria that he proposes as assisting in an estimate of population." Chapter 5 examines The Poor Laws of Pitt the Younger. Chapter 6 examines the rapid growth of new colonies such as the former Thirteen Colonies of the United States of America. Chapter 7 examines checks on population such as pestilence and famine. Chapter 8 also examines a "probable error" by Wallace "that the difficulty arising from population is at a great distance." Chapters 16 and 17 examine the causes of the wealth of states, including criticisms of Adam Smith and Richard Price. English wealth is compared with Chinese poverty. Chapters 18 and 19 set out a theodicy to explain the problem of evil in terms of natural theology. This views the world as "a mighty process for awakening matter" in which the Supreme Being acting "according to general laws" created "wants of the body" as "necessary to create exertion" which forms "the reasoning faculty". In this way, the principle of population would "tend rather to promote, than impede the general purpose of Providence." The 1st edition influenced writers of natural theology such as William Paley and Thomas Chalmers. 2nd to 6th editionsFollowing both widespread praise and criticism of his essay, Malthus revised his arguments and recognized other influences:[citation needed]

The 2nd edition, published in 1803 (with Malthus now clearly identified as the author), was entitled "An Essay on the Principle of Population; or, a View of its Past and Present Effects on Human Happiness; with an enquiry into our Prospects respecting the Future Removal or Mitigation of the Evils which it occasions." Malthus advised that the 2nd edition "may be considered as a new work",[citation needed] and the subsequent editions were all minor revisions of the 2nd edition. These were published in 1806, 1807, 1817, and 1826. By far the biggest change was in how the 2nd to 6th editions of the essay were structured, and the most copious and detailed evidence that Malthus presented, more than any previous such book on population. Essentially, for the first time, Malthus examined his own Principle of Population on a region-by-region basis of world population. The essay was organized in four books:

Due in part to the highly influential nature of Malthus' work (see main article Thomas Malthus), this approach is regarded as pivotal in establishing the field of demography and even to him being regarded as its founding father.[26] The following controversial quote appears in the second edition:[citation needed]

Ecologist Professor Garrett Hardin claims that the preceding passage inspired hostile reactions from many critics. The offending passage of Malthus' essay appeared in the 2nd edition only, as Malthus felt obliged to remove it.[27] From the 2nd edition onwards – in Book IV – Malthus advocated moral restraint as an additional, and voluntary, check on population. This included such measures as sexual abstinence and late marriage. As noted by Professor Robert M. Young, Malthus dropped his chapters on natural theology from the 2nd edition onwards. Also, the essay became less of a personal response to Godwin and Condorcet. A Summary ViewA Summary View on the Principle of Population was published in 1830. The author was identified as Rev. T.R. Malthus, A.M., F.R.S. Malthus wrote A Summary View for those who did not have the leisure to read the full essay and, as he put it, "to correct some of the misrepresentations which have gone abroad respecting two or three of the most important points of the Essay".[28] A Summary View ends with a defense of the Principle of Population against the charge that it "impeaches the goodness of the Deity, and is inconsistent with the letter and spirit of the scriptures". Malthus died in 1834 leaving this as his final word on the Principle of Population. Other works that influenced Malthus

Reception, criticism, and legacy of EssayPersonaliaMalthus became subject to extreme personal criticism. People who knew nothing about his private life criticised him both for having no children and for having too many. In 1819, Shelley, berating Malthus as a priest, called him "a eunuch and a tyrant".[29] Marx repeated the idea, adding that Malthus had taken the vow of celibacy, and called him "superficial", "a professional plagiarist", "the agent of the landed aristocracy", "a paid advocate" and "the principal enemy of the people".[30] In the 20th century an editor of the Everyman edition of Malthus claimed that Malthus had practised population control by begetting eleven girls.[31] In fact, Malthus fathered two daughters and one son. Garrett Hardin provides an overview of such personal comments.[27] Early influenceThe position held by Malthus as professor at the Haileybury training college, to his death in 1834, gave his theories some influence over Company rule in India.[32] According to Peterson, William Pitt the Younger (in office: 1783–1801 and 1804–1806), on reading the work of Malthus, withdrew a Bill he had introduced that called for the extension of Poor Relief. Concerns about Malthus's theory helped promote the idea of a national population census in the UK. Government official John Rickman became instrumental in the carrying out of the first modern British census in 1801, under Pitt's administration. In the 1830s Malthus's writings strongly influenced Whig reforms which overturned Tory paternalism and brought in the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. Malthus convinced most economists that even while high fertility might increase the gross output, it tended to reduce output per capita. David Ricardo and Alfred Marshall admired Malthus, and so came under his influence. Early converts to his population theory included William Paley. Despite Malthus's opposition to contraception, his work exercised a strong influence on Francis Place (1771–1854), whose neo-Malthusian movement became the first to advocate contraception. Place published his Illustrations and Proofs of the Principles of Population in 1822.[33] Early responses in the Malthusian controversyIn Ireland, where (writing to Ricardo in 1817) Malthus proposed that "to give full effect to the natural resources of the country a great part of the population should be swept from the soil",[34] an early "refutation" of the Essay on Population was offered by George Ensor. In his Inquiry Concerning the Population of Nations (1818), he professed "astonishment" at Malthus's "general indemnity" of the rich and powerful:

Seizing upon Malthus's proposition that "manufacturing is at once the consequence of a better distribution of property and the cause of further improvement", Ensor was later to press the argument that poverty is sustained, not by a reckless propensity to breed, but by government's indulgence of the heedless concentration of private wealth.[36] A similar broadside was published in 1821 by Whitely Stokes.[37] His Observations on the population and resources of Ireland found fault in Malthus's calculations and juxtapositions, and insisting upon the advantages mankind derives from "improved industry, improved conveyance, improvements in morals, government and religion", argued that Ireland's difficulty lay not in her "numbers", but in her indifferent government.[38] William Godwin criticized Malthus's criticisms of his own arguments in his book Of Population (1820).[39] Other theoretical and political critiques of Malthus and Malthusian thinking emerged soon after the publication of the first Essay on Population, most notably in the work of Robert Owen, of the essayist William Hazlitt (1807)[40] and of the economist Nassau William Senior,[41] and moralist William Cobbett. True Law of Population (1845) was by politician Thomas Doubleday, an adherent of Cobbett's views. John Stuart Mill strongly defended the ideas of Malthus in his 1848 work, Principles of Political Economy (Book II, Chapters 11–13). Mill considered the criticisms of Malthus made thus far to have been superficial. The American economist Henry Charles Carey rejected Malthus's argument in his magnum opus of 1858–59, The Principles of Social Science. Carey maintained that the only situation in which the means of subsistence will determine population growth is one in which a given society is not introducing new technologies or not adopting forward-thinking governmental policy, and that population regulated itself in every well-governed society, but its pressure on subsistence characterized the lower stages of civilization. Another American, Daniel Raymond stated in his Thoughts on Political Economy (1820) "Although his theory is founded upon the principles of nature, and although it is impossible to discover any flaw in his reasoning, yet the mind instinctively revolts at the conclusions to which he conducts it, and we are disposed to reject the theory, even though we could give no good reason." This rejection of conclusions, coincides with Malthus's own observation that "America had not reached the stage where the difficulties in increasing production were great enough appreciably to check population".[42] In France, ideas concerning overpopulation had been prevalent some time before Malthus published his Essay, "Pre-Malthusian French writers had developed an unorganized set of observations more in accord with fact and probability than Malthus' well-integrated doctrine". By 1798 two broad bodies of thought had already begun to form in the country, those who like Malthus, saw a danger in overpopulation and the stressing of productive limits, and the "pro-populationists" who argued that population growth would lead to productivity growth, and thus should be encouraged.[43] Marxist oppositionAnother strand of opposition to Malthus's ideas started in the middle of the 19th century with the writings of Friedrich Engels (Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy, 1844) and Karl Marx (Capital, 1867). Engels and Marx argued that what Malthus saw as the problem of the pressure of population on the means of production actually represented the pressure of the means of production on population. They thus viewed it in terms of their concept of the reserve army of labour. In other words, the seeming excess of population that Malthus attributed to the seemingly innate disposition of the poor to reproduce beyond their means actually emerged as a product of the very dynamic of capitalist economy. Engels called Malthus's hypothesis "the crudest, most barbarous theory that ever existed, a system of despair which struck down all those beautiful phrases about love thy neighbour and world citizenship".[44] Engels also predicted[44] that science would solve the problem of an adequate food supply. In the Marxist tradition, Lenin sharply criticized Malthusian theory and its neo-Malthusian version,[45] calling it a "reactionary doctrine" and "an attempt on the part of bourgeois ideologists to exonerate capitalism and to prove the inevitability of privation and misery for the working class under any social system". In addition, many Russian philosophers could not easily apply Malthus' population theory to Russian society in the 1840s. In England, where Malthus lived, population was rapidly increasing but suitable agricultural land was limited. Russia, on the other hand, had extensive land with agricultural potential yet a relatively sparse population. It is possible that this discrepancy between Russian and English realities contributed to the rejection of Malthus' Essay on the Principle of Population by key Russian thinkers.[46] Another difference which contributed to the confusion and ultimately the rejection of Malthus's argument in Russia was its cultural basis in English capitalism.[46] This political contrast helps explain why it took Russia twenty years to publish a review of the work and fifty years to translate Malthus's Essay.[46] Later responsesIn the 20th century, those who regarded Malthus as a failed prophet of doom included an editor of Nature, John Maddox.[47] Economist Julian Lincoln Simon has criticised Malthus's conclusions.[48] He notes that despite the predictions of Malthus and of the neo-Malthusians, massive geometric population growth in the 20th century did not result in a Malthusian catastrophe. Many factors have been identified as having contributed: general improvements in farming methods (industrial agriculture), mechanization of work (tractors), the introduction of high-yield varieties of wheat and other plants (Green Revolution), the use of pesticides to control crop pests. Each played a role.[49] The enviro-sceptic Bjørn Lomborg presented data to argue the case that the environment had actually improved,[50] and that calories produced per day per capita globally went up 23% between 1960 and 2000, despite the doubling of the world population in that period.[51] From the opposite angle, Romanian American economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, a progenitor in economics and a paradigm founder of ecological economics, has argued that Malthus was too optimistic, as he failed to recognize any upper limit to the growth of population—only, the geometric increase in human numbers is occasionally slowed down (checked) by the arithmetic increase in agricultural produce, according to Malthus' simple growth model; but some upper limit to population is bound to exist, as the total amount of agricultural land—actual as well as potential—on Earth is finite, Georgescu-Roegen points out.[52]: 366–369 Georgescu-Roegen further argues that the industrialised world's increase in agricultural productivity since Malthus' day has been brought about by a mechanisation that has substituted a scarcer source of input for the more abundant input of solar radiation: Machinery, chemical fertilisers and pesticides all rely on mineral resources for their operation, rendering modern agriculture—and the industrialised food processing and distribution systems associated with it—almost as dependent on Earth's mineral stock as the industrial sector has always been. Georgescu-Roegen cautions that this situation is a major reason why the carrying capacity of Earth—that is, Earth's capacity to sustain human populations and consumption levels—is bound to decrease sometime in the future as Earth's finite stock of mineral resources is presently being extracted and put to use.[53]: 303 Political advisor Jeremy Rifkin and ecological economist Herman Daly, two students of Georgescu-Roegen, have raised similar neo-Malthusian concerns about the long run drawbacks of modern mechanised agriculture.[54]: 136–140 [55]: 10f Anthropologist Eric Ross depicts Malthus's work as a rationalization of the social inequities produced by the Industrial Revolution, anti-immigration movements, the eugenics movement[clarification needed] and the various international development movements.[56] Social theoryDespite use of the term "Malthusian catastrophe" by detractors such as economist Julian Simon (1932–1998), Malthus himself did not write that mankind faced an inevitable future catastrophe. Rather, he offered an evolutionary social theory of population dynamics as it had acted steadily throughout all previous history.[57] Eight major points regarding population dynamics appear in the 1798 Essay:[citation needed]

Malthusian social theory influenced Herbert Spencer's idea of the survival of the fittest,[58] and the modern ecological-evolutionary social theory of Gerhard Lenski and Marvin Harris.[59] Malthusian ideas have thus contributed to the canon of socioeconomic theory. The first Director-General of UNESCO, Julian Huxley, wrote of The crowded world in his Evolutionary Humanism (1964), calling for a world population policy. Huxley openly criticised communist and Roman Catholic attitudes to birth control, population control and overpopulation. BiologyCharles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace each read and acknowledged the role played by Malthus in the development of their own ideas. Darwin referred to Malthus as "that great philosopher",[60] and said of his On the Origin of Species: "This is the doctrine of Malthus, applied with manifold force to the animal and vegetable kingdoms, for in this case there can be no artificial increase of food, and no prudential restraint from marriage".[61] Darwin also wrote:

Wallace stated:

Ronald Fisher commented sceptically on Malthusianism as a basis for a theory of natural selection.[63] Fisher emphasised the role of fecundity (reproductive rate), rather than assume actual conditions would not reduce future births.[64] John Maynard Smith doubted that famine functioned as the great leveller, as portrayed by Malthus, but he also accepted the basic premises:

Later parallelsWriters who have presented ideas that have paralleled various of those of Malthus include: Paul R. Ehrlich who has written several books predicting famine as a result of population increase: The Population Bomb (1968); Population, resources, environment: issues in human ecology (1970, with Anne Ehrlich); The end of affluence (1974, with Anne Ehrlich); The population explosion (1990, with Anne Ehrlich). In the late 1960s Ehrlich predicted that hundreds of millions would die from a coming overpopulation-crisis in the 1970s. Other examples of work that has been accused of "Malthusianism" include the 1972 book The Limits to Growth (published by the Club of Rome) and the Global 2000 report to the then President of the United States Jimmy Carter. Isaac Asimov also produced many essays on topics related to overpopulation.[65] Ecological economist Herman Daly has recognized the influence of Malthus on his own work on steady-state economics.[55]: xvi Other scholars have more recently[update] linked population and economics to a third variable, political change and political violence, and to show how the variables interact. In the early 1980s, Jack Goldstone linked population variables to the English Revolution of 1640–1660[citation needed] and David Lempert devised a model of demographics, economics, and political change in the multi-ethnic country of Mauritius.[66] Goldstone has since modeled other revolutions by looking at demographics and economics[citation needed] and Lempert has explained Stalin's purges and the Russian Revolution of 1917 in terms of demographic factors that drive political economy. Ted Robert Gurr has also modeled political violence, such as in the Palestinian territories and in Rwanda/Congo (two of the world's regions of most rapidly growing population) using similar variables in several comparative cases. These approaches suggest that political ideology follows demographic forces. Physics professor, Albert Allen Bartlett, has lectured over 1,500 times on "Arithmetic, Population, and Energy", promoting sustainable living and explaining the mathematics of overpopulation. Malthus is directly referenced by science-fiction author K. Eric Drexler in Engines of Creation (1986): "In a sense, opening space will burst our limits to growth, since we know of no end to the universe. Nevertheless, Malthus was essentially right." The Malthusian growth model now bears Malthus's name. The logistic function of Pierre François Verhulst (1804–1849) results in the S-curve. Verhulst developed the logistic growth model favored by so many critics of the Malthusian growth model in 1838 only after reading Malthus's essay. See also

References

External linksWikisource has original text related to this article:

|

||||||||||||||