|

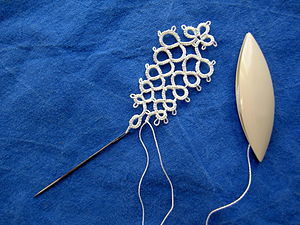

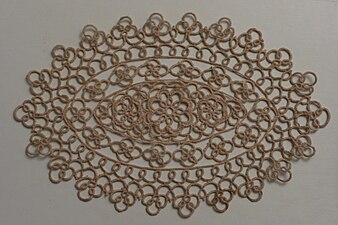

Tatting Tatting is a technique for handcrafting a particularly durable lace from a series of knots and loops.[1] Tatting can be used to make lace edging as well as doilies, collars, accessories such as earrings, necklaces, waist beads, and other decorative pieces. The lace is formed by a pattern of rings and chains formed from a series of cow hitch or half-hitch knots, called double stitches, over a core thread. Gaps can be left between the stitches to form picots, which are used for practical construction as well as decorative effect. In German, tatting is usually known by the Italian-derived word Occhi or as Schiffchenarbeit, which means "work of the little boat", referring to the boat-shaped shuttle; in Italian, tatting is called chiacchierino, which means "chatty".[2] Technique and materialsShuttle tatting  Tatting with a shuttle is the earliest method of creating tatted lace. A tatting shuttle facilitates tatting by holding a length of wound thread and guiding it through loops to make the requisite knots. Historically, it was a metal or ivory pointed-oval shape less than 3 inches (76 mm) long, but shuttles come in a variety of shapes and materials. Shuttles often have a point or hook on one end to aid in the construction of the lace. Antique shuttles and unique shuttles have become sought after by collectors — even those who do not tat. To make the lace, the tatter wraps the thread around one hand and manipulates the shuttle with the other hand. No tools other than the thread, the hands and the shuttle are used, though a crochet hook may be necessary if the shuttle does not have a point or hook. Needle tatting  Traditional shuttle tatting may be simulated using a tatting needle or doll needle instead of a shuttle. There are two basic techniques for needle tatting. With the more widely disseminated technique, a double thread passes through the stitches.[citation needed] The result is similar to shuttle tatting but is slightly thicker and looser.[citation needed] The second technique more closely approximates shuttle tatting because a single thread passes through the stitches. The earliest evidence for needle tatting dates from April 1917, in an article by M.E. Rozella, published in The Modern Priscilla.[3] A tatting needle is a long, blunt needle that does not change thickness at the eye of the needle. The needle used must match the thickness of the thread chosen for the project. Rather than winding the shuttle, the needle is threaded with a length of thread. To work with a second color, a second needle is used. Although needle tatting looks similar to shuttle tatting, it differs in structure and is slightly thicker and looser because both the needle and the thread must pass through the stitches. However, it may be seen that the Victorian tatting pin would function as a tatting needle. As well, Florence Hartley refers in The Ladies' Hand Book of Fancy and Ornamental Work (1859) to the use of the tatting needle, so it must have originated prior to the mid-1800s. In the late 20th century, tatting needles became commercially available in a variety of sizes, from fingering yarn down to size 80 tatting thread. Few patterns are written specifically for needle tatting; some shuttle tatting patterns may be used without modification. Cro-tattingCro-tatting combines needle tatting with crochet. The cro-tatting tool is a tatting needle with a crochet hook at the end. One can also cro-tat with a bullion crochet hook or a very straight crochet hook. In the 19th century, "crochet tatting" patterns were published which simply called for a crochet hook. One of the earliest patterns is for a crocheted afghan with tatted rings forming a raised design.[4] Patterns are available in English and are equally divided between yarn and thread. In its most basic form, the rings are tatted with a length of plain thread between them, as in single-shuttle tatting. In modern patterns, beginning in the early 20th century, the rings are tatted and the arches or chains are crocheted. Many people consider cro-tatting more difficult than crochet or needle tatting. Some tatting instructors recommend using a tatting needle and a crochet hook to work cro-tatting patterns. Stitches of cro-tatting (and needle tatting before a ring is closed) unravel easily, unlike tatting made with a shuttle. A form of tatting called Takashima Tatting, invented by Toshiko Takashima, exists in Japan. Takashima Tatting uses a custom needle with a hook on one end.[5] It is not that widespread however (in Japan the primary form of tatting is shuttle tatting, and needle tatting is virtually unknown.). MaterialsOlder designs, especially through the early 1900s, tend to use fine white or ivory thread (50 to 100 widths to the inch) and intricate designs. Often they were constructed of small pieces 10 cm or less in diameter, which were then tied to each other to form a larger piece — a shawl, veil or umbrella, for example. This thread was either made of silk or a silk blend, to allow for improper stitches to be easily removed.[citation needed] The mercerization process strengthened cotton threads and spread their use in tatting. Newer designs from the 1920s and onward often use thicker thread in one or more colors, as well as newer joining methods, to reduce the number of thread ends to be hidden. The best thread for tatting is a "hard" thread that does not untwist readily. Cordonnet thread is a common tatting thread; Perl cotton is an example of a beautiful cord that is nonetheless a bit loose for tatting purposes. Some tatting designs incorporate ribbons and beads. Patterns Older patterns use a longhand notation to describe the stitches needed, while newer patterns tend to make extensive use of abbreviations such as "ds" to mean "double stitch," and an almost mathematical-looking notation. The following examples describe the same small piece of tatting (the first ring in the Hen and Chicks pattern)

Some tatters prefer a visual pattern where the design is drawn schematically with annotations indicating the number of double stitches and order of construction. This can either be used on its own or alongside a written pattern. Books with tatting patterns are widely available. Anne Orr, a notable needlework editor, quilt designer, and textile artist,[6] was recognized for the quality of her work and her work has been reprinted for contemporary tatters.[7] Modern tatting pattern books sometimes include jewelry items that can be adorned with beads.[8][9] History Old catalog of samples on command. Top left sample is tatted lace. Tatting may have developed from netting and decorative ropework as sailors and fishermen would put together motifs for girlfriends and wives at home. Decorative ropework employed on ships includes techniques (esp. coxcombing) that show striking similarity with tatting. A good description of this can be found in Knots, Splices and Fancywork.[10] Some believe tatting originated over 200 years ago, often citing shuttles seen in 18th-century paintings of women such as Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Princess Marie Adélaïde of France, and Anne, Countess of Albemarle. A close inspection of those paintings, however, shows that the shuttles in question are too large to be tatting shuttles, and that they are actually knotting shuttles. There is no documentation of or examples of tatted lace that dates prior to 1800. All available evidence shows that tatting originated in the early 19th century.[11] However, recent research by Cary Karp demonstrates some potential connections between the two fiber arts. According to Karp, "Knotting and tatting did appear sequentially in the historical record and can reasonably be regarded separately...the demarcation between the structures that characterise knotting, and the central elements of tatting, was not as clear cut as is often maintained."[12] As most fashion magazines and home economics magazines from the first half of the 20th century attest, tatting had a substantial following. When fashion included feminine touches such as lace collars and cuffs, and inexpensive yet nice baby shower gifts were needed, this creative art flourished. As the fashion moved to a more modern look and technology made lace an easy and inexpensive commodity to purchase, hand-made lace began to decline.[citation needed] Tatting has been used in occupational therapy to keep convalescent patients' hands and minds active during recovery, as documented, for example, in Betty MacDonald's The Plague & I.[citation needed] Workshops and competitions in tatting continue to be available from lace guilds and organizations.[13] Gallery

Notes

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Tatting.

|