|

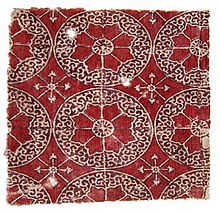

Textile arts     Textile arts are arts and crafts that use plant, animal, or synthetic fibers to construct practical or decorative objects. Textiles have been a fundamental part of human life since the beginning of civilization.[1][2] The methods and materials used to make them have expanded enormously, while the functions of textiles have remained the same, there are many functions for textiles. Whether it be clothing or something decorative for the house/shelter. The history of textile arts is also the history of international trade. Tyrian purple dye was an important trade good in the ancient Mediterranean. The Silk Road brought Chinese silk to India, Africa, and Europe, and, conversely, Sogdian silk to China. Tastes for imported luxury fabrics led to sumptuary laws during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The Industrial Revolution was shaped largely by innovation in textiles technology: the cotton gin, the spinning jenny, and the power loom mechanized production and led to the Luddite rebellion. ConceptsThe word textile is from Latin texere which means "to weave", "to braid" or "to construct".[1] The simplest textile art is felting, in which animal fibers are matted together using heat and moisture. Most textile arts begin with twisting or spinning and plying fibers to make yarn (called thread when it is very fine and rope when it is very heavy). The yarn is then knotted, looped, braided, or woven to make flexible fabric or cloth, and cloth can be used to make clothing and soft furnishings. All of these items – felt, yarn, fabric, and finished objects – are collectively referred to as textiles.[3] The textile arts also include those techniques which are used to embellish or decorate textiles – dyeing and printing to add color and pattern; embroidery and other types of needlework; tablet weaving; and lace-making. Construction methods such as sewing, knitting, crochet, and tailoring, as well as the tools employed (looms and sewing needles), techniques employed (quilting and pleating) and the objects made (carpets, kilims, hooked rugs, and coverlets) all fall under the category of textile arts. FunctionsFrom early times, textiles have been used to cover the human body and protect it from the elements; to send social cues to other people; to store, secure, and protect possessions; and to soften, insulate, and decorate living spaces and surfaces.[4] The persistence of ancient textile arts and functions, and their elaboration for decorative effect, can be seen in a Jacobean era portrait of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales by Robert Peake the Elder (above). The prince's capotain hat is made of felt using the most basic of textile techniques. His clothing is made of woven cloth, richly embroidered in silk, and his stockings are knitted. He stands on an oriental rug of wool which softens and warms the floor, and heavy curtains both decorate the room and block cold drafts from the window. Goldwork embroidery on the tablecloth and curtains proclaim the status of the home's owner, in the same way that the felted fur hat, sheer linen shirt trimmed with reticella lace, and opulent embroidery on the prince's clothes proclaim his social position.[5] Textiles as artTraditionally the term art was used to refer to any skill or mastery, a concept which altered during the Romantic period of the nineteenth century, when art came to be seen as "a special faculty of the human mind to be classified with religion and science".[6] This distinction between craft and fine art is applied to the textile arts as well, where the term fiber art or textile art is now used to describe textile-based decorative objects which are not intended for practical use.[7][8] History of plant use in textile artsNatural fibers have been an important aspect of human society since 7000 B.C.,[9] and it is suspected that they were first used in ornamental cloths since 400 B.C. in India where cotton was first grown.[10] Natural fibers have been used for the past 4000 to 5000 years to make cloth, and plant and animal fibers were the only way that clothing and fabrics could be created up until 1885 when the first synthetic fiber was made.[9] Cotton and flax are two of the most common natural fibers that are used today, but historically natural fibers were made of most parts of the plant, including bark, stem, leaf, fruit, seed hairs, and sap.[10] Flax Flax is believed to be the oldest fiber that was used to create textiles, as it was found in the tombs of mummies from as early as 6500 B.C.[10][9][11] The fibers from the flax are taken from the filaments in the stem of the plant, spun together to create long strands, and then woven into long pieces of linen that were used from anything from bandages to clothing and tapestries.[11] Each fiber's length depends on the height of the leaf that it is serving, with 10 filaments in a bundle serving each leaf on the plant. Each filament is the same thickness, giving it a consistency that is ideal for spinning yarn.[9] The yarn was best used on warping boards or warping reels to create large pieces of cloth that could be dyed and woven into different patterns to create elaborate tapestries and embroideries.[10] One example of how linen was used is in the picture of a bandage that a mummy was wrapped in, dated between 305 and 30 B.C. Some of the bandages were painted with hieroglyphs if the person being buried was of importance to the community. Cotton Cotton was first used in 5000 B.C. in India and the Middle East, and spread to Europe after they invaded India in 327 B.C. The manufacture and production of cotton spread rapidly in the 18th century, and it quickly became one of the most important textile fibers because of its comfort, durability, and absorbency.[9] Cotton fibers are seed hairs formed in a capsule that grows after the plant flowers. The fibers complete their growth cycle and burst to release about 30 seeds that each have between 200 and 7000 seed hairs that are between 22 and 50 millimeters long. About 90% of the seed hairs are cellulose, with the other 10% being wax, pectate, protein, and other minerals.[9] Once it is processed, cotton can be spun into yarn of various thicknesses to be woven or knitted into various different products such as velvet, chambray, corduroy, jersey, flannel, and velour that can be used in clothing tapestries, rugs, and drapes, as shown in the image of the cotton tapestry that was woven in India.[10] Plant fiber identification in ancient textilesLight microscopy, normal transmission electron microscopy, and most recently scanning electron microscopy (SEM) are used to study ancient textile remains to determine what natural fibers were used to create them.[12] Once textiles are found, the fibers are teased out using a light microscope and an SEM is used to look for characteristics in the textile that show what plant it is made of.[12] In flax, for example, scientists look for longitudinal striations that show the cells of the plant stem and cross striations and nodes that are specific to flax fibers. Cotton is identified by the twist that occurs in the seed hairs when the fibers are dried to be woven.[12] This knowledge helps us to learn where and when the cultivation of plants that are used in textiles first occurred, confirming the previous knowledge that was gained from studying the era in which different textile arts aligned with from a perspective of design.[10][12] Future of plants in textile artWhile plant use in textile art is still common today, there are new innovations being developed, such as Suzanne Lee's art installation "BioCouture". Lee uses fermentation to create a plant-based paper sheet that can be cut and sewn just like cloth- ranging in thickness from thin plastic-like materials up to thick leather-like sheets.[13] The garments are "disposable" because they are made entirely of plant based products and are completely biodegradable. Within her project, Lee places a large emphasis on making the clothing look fashionable by using avant-garde style and natural dyes made from fruits because compostable clothing is not appealing to most shoppers.[13] In addition, there is a possibility to create designs with the plants by tearing or cutting the growing sheet and allowing it to heal to create a pattern made of scars on the textile.[13] The possibilities to use this textile in art installations is incredible because artists would have the ability to create a living art piece, such as Lee does with her clothing. Textile arts by region

List of contemporary textile artists

Gallery

See alsoNotes

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Textile arts. Wikiquote has quotations related to Textile arts.

|