|

Engraving

Engraving is the practice of incising a design on a hard, usually flat surface by cutting grooves into it with a burin. The result may be a decorated object in itself, as when silver, gold, steel, or glass are engraved, or may provide an intaglio printing plate, of copper or another metal,[1] for printing images on paper as prints or illustrations; these images are also called "engravings". Engraving is one of the oldest and most important techniques in printmaking. Wood engravings, a form of relief printing and stone engravings, such as petroglyphs, are not covered in this article.

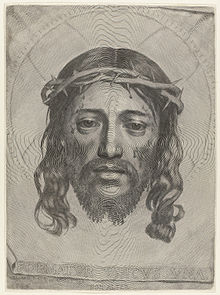

"Engraving" is loosely but incorrectly used for any old black and white print; it requires a degree of expertise to distinguish engravings from prints using other techniques such as etching in particular, but also mezzotint and other techniques. Many old master prints also combine techniques on the same plate, further confusing matters. Line engraving and steel engraving cover use for reproductive prints, illustrations in books and magazines, and similar uses, mostly in the 19th century, and often not actually using engraving. Traditional engraving, by burin or with the use of machines, continues to be practised by goldsmiths, glass engravers, gunsmiths and others, while modern industrial techniques such as photoengraving and laser engraving have many important applications. Engraved gems were an important art in the ancient world, revived at the Renaissance, although the term traditionally covers relief as well as intaglio carvings, and is essentially a branch of sculpture rather than engraving, as drills were the usual tools. TermsEcce Homo by Jan Norblin, original print (left) and copper plate (right) with composition reversed (National Museum in Warsaw) Other terms often used for printed engravings are copper engraving, copper-plate engraving or line engraving. Steel engraving is the same technique, on steel or steel-faced plates, and was mostly used for banknotes, illustrations for books, magazines and reproductive prints, letterheads and similar uses from about 1790 to the early 20th century, when the technique became less popular, except for banknotes and other forms of security printing. Especially in the past, "engraving" was often used very loosely to cover several printmaking techniques, so that many so-called engravings were in fact produced by totally different techniques, such as etching or mezzotint. "Hand engraving[2]" is a term sometimes used for engraving objects other than printing plates, to inscribe or decorate jewellery, firearms, trophies, knives and other fine metal goods. Traditional engravings in printmaking are also "hand engraved", using just the same techniques to make the lines in the plate. Process Engravers use a hardened steel tool called a burin, or graver, to cut the design into the surface, most traditionally a copper plate.[3] However, modern hand engraving artists use burins or gravers to cut a variety of metals such as silver, nickel, steel, brass, gold, and titanium, in applications ranging from weaponry to jewellery to motorcycles to found objects. Modern professional engravers can engrave with a resolution of up to 40 lines per mm in high grade work creating game scenes and scrollwork. Dies used in mass production of molded parts are sometimes hand engraved to add special touches or certain information such as part numbers. In addition to hand engraving, there are engraving machines that require less human finesse and are not directly controlled by hand. They are usually used for lettering, using a pantographic system. There are versions for the insides of rings and also the outsides of larger pieces. Such machines are commonly used for inscriptions on rings, lockets and presentation pieces. Tools and gravers or burins Gravers come in a variety of shapes and sizes that yield different line types. The burin produces a unique and recognizable quality of line that is characterized by its steady, deliberate appearance and clean edges. The angle tint tool has a slightly curved tip that is commonly used in printmaking. Florentine liners are flat-bottomed tools with multiple lines incised into them, used to do fill work on larger areas or to create uniform shade lines that are fast to execute. Ring gravers are made with particular shapes that are used by jewelry engravers in order to cut inscriptions inside rings. Flat gravers are used for fill work on letters, as well as "wriggle" cuts on most musical instrument engraving work, remove background, or create bright cuts. Knife gravers are for line engraving and very deep cuts. Round gravers, and flat gravers with a radius, are commonly used on silver to create bright cuts (also called bright-cut engraving), as well as other hard-to-cut metals such as nickel and steel. Square or V-point gravers are typically square or elongated diamond-shaped and used for cutting straight lines. V-point can be anywhere from 60 to 130 degrees, depending on purpose and effect. These gravers have very small cutting points. Other tools such as mezzotint rockers, roulets and burnishers are used for texturing effects. Burnishing tools can also be used for certain stone setting techniques.  Musical instrument engraving on American-made brass instruments flourished in the 1920s and utilizes a specialized engraving technique where a flat graver is "walked" across the surface of the instrument to make zig-zag lines and patterns. The method for "walking" the graver may also be referred to as "wriggle" or "wiggle" cuts. This technique is necessary due to the thinness of metal used to make musical instruments versus firearms or jewelry. Wriggle cuts are commonly found on silver Western jewelry and other Western metal work. Tool geometryTool geometry is extremely important for accuracy in hand engraving. When sharpened for most applications, a graver has a "face", which is the top of the graver, and a "heel", which is the bottom of the graver; not all tools or application require a heel. These two surfaces meet to form a point that cuts the metal. The geometry and length of the heel helps to guide the graver smoothly as it cuts the surface of the metal. When the tool's point breaks or chips, even on a microscopic level, the graver can become hard to control and produces unexpected results. Modern innovations have brought about new types of carbide that resist chipping and breakage, which hold a very sharp point longer between resharpening than traditional metal tools. Tool sharpeningPreparatory drawing by Hans von Aachen for a portrait print of Emperor Rudolph II, National Library of Poland and Aegidius Sadeler's print from 1603, Metropolitan Museum of Art Sharpening a graver or burin requires either a sharpening stone or wheel. Harder carbide and steel gravers require diamond-grade sharpening wheels; these gravers can be polished to a mirror finish using a ceramic or cast iron lap, which is essential in creating bright cuts. Several low-speed, reversible sharpening systems made specifically for hand engravers are available that reduce sharpening time. Fixtures that secure the tool in place at certain angles and geometries are also available to take the guesswork from sharpening to produce accurate points. Very few master engravers exist today who rely solely on "feel" and muscle memory to sharpen tools. These master engravers typically worked for many years as an apprentice, most often learning techniques decades before modern machinery was available for hand engravers. These engravers typically trained in such countries as Italy and Belgium, where hand engraving has a rich and long heritage of masters. Artwork designDesign or artwork is generally prepared in advance, although some professional and highly experienced hand engravers are able to draw out minimal outlines either on paper or directly on the metal surface just prior to engraving. The work to be engraved may be lightly scribed on the surface with a sharp point, laser marked, drawn with a fine permanent marker (removable with acetone) or pencil, transferred using various chemicals in conjunction with inkjet or laser printouts, or stippled. Engraving artists may rely on hand drawing skills, copyright-free designs and images, computer-generated artwork, or common design elements when creating artwork. Handpieces Originally, handpieces varied little in design as the common use was to push with the handle placed firmly in the center of the palm. With modern pneumatic engraving systems, handpieces are designed and created in a variety of shapes and power ranges. Handpieces are made using various methods and materials. Knobs may be handmade from wood, molded and engineered from plastic, or machine-made from brass, steel, or other metals. Cutting the surface The actual engraving is traditionally done by a combination of pressure and manipulating the work-piece. The traditional "hand push" process is still practiced today, but modern technology has brought various mechanically assisted engraving systems. Most pneumatic engraving systems require an air source that drives air through a hose into a handpiece, which resembles a traditional engraving handle in many cases, that powers a mechanism (usually a piston). The air is actuated by either a foot control (like a gas pedal or sewing machine) or newer palm / hand control. This mechanism replaces either the "hand push" effort or the effects of a hammer. The internal mechanisms move at speeds up to 15,000 strokes per minute, thereby greatly reducing the effort needed in traditional hand engraving. These types of pneumatic systems are used for power assistance only and do not guide or control the engraving artist. One of the major benefits of using a pneumatic system for hand engraving is the reduction of fatigue and decrease in time spent working. Hand engraving artists today employ a combination of hand push, pneumatic, rotary, or hammer and chisel methods. Hand push is still commonly used by modern hand engraving artists who create "bulino" style work, which is highly detailed and delicate, fine work; a great majority, if not all, traditional printmakers today rely solely upon hand push methods. Pneumatic systems greatly reduce the effort required for removing large amounts of metal, such as in deep relief engraving or Western bright cut techniques. FinishingFinishing the work is often necessary when working in metal that may rust or where a colored finish is desirable, such as a firearm. A variety of spray lacquers and finishing techniques exist to seal and protect the work from exposure to the elements and time. Finishing also may include lightly sanding the surface to remove small chips of metal called "burrs" that are very sharp and unsightly. Some engravers prefer high contrast to the work or design, using black paints or inks to darken removed (and lower) areas of exposed metal. The excess paint or ink is wiped away and allowed to dry before lacquering or sealing, which may or may not be desired by the artist. Modern hand engraving Because of the high level of microscopic detail that can be achieved by a master engraver, counterfeiting of engraved designs is almost impossible, and modern banknotes are almost always engraved, as are plates for printing money, checks, bonds and other security-sensitive papers. The engraving is so fine that a normal printer cannot recreate the detail of hand-engraved images, nor can it be scanned. At the United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing, more than one hand engraver will work on the same plate, making it nearly impossible for one person to duplicate all the engraving on a particular banknote or document. The modern discipline of hand engraving, as it is called in a metalworking context, survives largely in a few specialized fields. The highest levels of the art are found on firearms and other metal weaponry, jewellery, silverware and musical instruments. In most commercial markets today, hand engraving has been replaced with milling using CNC engraving or milling machines. Still, there are certain applications where use of hand engraving tools cannot be replaced. Machine engravingIn some instances, images or designs can be transferred to metal surfaces via mechanical process. One such process is roll stamping or roller-die engraving. In this process, a hardened image die is pressed against the destination surface using extreme pressure to impart the image. In the 1800s pistol cylinders were often decorated via this process to impart a continuous scene around the surface. Computer-aided machine engraving Engraving machines such as the K500 (packaging) or K6 (publication) by Hell Gravure Systems use a diamond stylus to cut cells. Each cell creates one printing dot later in the process. A K6 can have up to 18 engraving heads each cutting 8.000 cells per second to an accuracy of .1 μm and below. They are fully computer-controlled and the whole process of cylinder-making is fully automated. It is now common place for retail stores (mostly jewellery, silverware or award stores) to have a small computer controlled engrave on site. This enables them to personalise the products they sell. Retail engraving machines tend to be focused around ease of use for the operator and the ability to do a wide variety of items including flat metal plates, jewelry of different shapes and sizes, as well as cylindrical items such as mugs and tankards. They will typically be equipped with a computer dedicated to graphic design that will enable the operator to easily design a text or picture graphic which the software will translate into digital signals telling the engraver machine what to do. Unlike industrial engravers, retail machines are smaller and only use one diamond head. This is interchangeable so the operator can use differently shaped diamonds for different finishing effects. They will typically be able to do a variety of metals and plastics. Glass and crystal engraving is possible, but the brittle nature of the material makes the process more time-consuming. Retail engravers mainly use two different processes. The first and most common 'Diamond Drag' pushes the diamond cutter through the surface of the material and then pulls to create scratches. These direction and depth are controlled by the computer input. The second is 'Spindle Cutter'. This is similar to Diamond Drag, but the engraving head is shaped in a flat V shape, with a small diamond and the base. The machine uses an electronic spindle to quickly rotate the head as it pushes it into the material, then pulls it along whilst it continues to spin. This creates a much bolder impression than diamond drag. It is used mainly for brass plaques and pet tags. With state-of-the-art machinery it is easy to have a simple, single item complete in under ten minutes. The engraving process with diamonds is state-of-the-art since the 1960s. Today laser engraving machines are in development but still mechanical cutting has proven its strength in economical terms and quality. More than 4,000 engravers make approx. 8 Mio printing cylinders worldwide per year. HistoryFor the printing process, see intaglio (printmaking). See also Steel engraving and line engraving  The first evidence for hominids engraving patterns is a chiselled shell, dating back between 540,000 and 430,000 years, from Trinil, in Java, Indonesia, where the first Homo erectus was discovered.[4] Hatched banding upon ostrich eggshells used as water containers found in South Africa in the Diepkloof Rock Shelter and dated to the Middle Stone Age around 60,000 BC are the next documented case of human engraving.[5] Engraving on bone and ivory is an important technique for the Art of the Upper Paleolithic, and larger engraved petroglyphs on rocks are found from many prehistoric periods and cultures around the world. In antiquity, the only engraving on metal that could be carried out is the shallow grooves found in some jewellery after the beginning of the 1st Millennium B.C. The majority of so-called engraved designs on ancient gold rings or other items were produced by chasing or sometimes a combination of lost-wax casting and chasing. Engraved gem is a term for any carved or engraved semi-precious stone; this was an important small-scale art form in the ancient world, and remained popular until the 19th century. However the use of glass engraving, usually using a wheel, to cut decorative scenes or figures into glass vessels, in imitation of hardstone carvings, appears as early as the first century AD,[6] continuing into the fourth century CE at urban centers such as Cologne and Rome,[7] and appears to have ceased sometime in the fifth century. Decoration was first based on Greek mythology, before hunting and circus scenes became popular, as well as imagery drawn from the Old and New Testament.[7] It appears to have been used to mimic the appearance of precious metal wares during the same period, including the application of gold leaf, and could be cut free-hand or with lathes. As many as twenty separate stylistic workshops have been identified, and it seems likely that the engraver and vessel producer were separate craftsmen.[6]  In the European Middle Ages goldsmiths used engraving to decorate and inscribe metalwork. It is thought that they began to print impressions of their designs to record them. From this grew the engraving of copper printing plates to produce artistic images on paper, known as old master prints, first in Germany in the 1430s.[citation needed] Italy soon followed. Many early engravers came from a goldsmithing background. The first and greatest period of the engraving was from about 1470 to 1530, with such masters as Martin Schongauer, Albrecht Dürer, and Lucas van Leiden.  Thereafter engraving tended to lose ground to etching, which was a much easier technique for the artist to learn. But many prints combined the two techniques: although Rembrandt's prints are generally all called etchings for convenience, many of them have some burin or drypoint work, and some have nothing else. By the nineteenth century, most engraving was for commercial illustration. Before the advent of photography, engraving was used to reproduce other forms of art, for example paintings. Engravings continued to be common in newspapers and many books into the early 20th century, as they were cheaper to use in printing than photographic images. Many classic postage stamps were engraved, although the practice is now mostly confined to particular countries, or used when a more "elegant" design is desired and a limited color range is acceptable.  Modifying the relief designs on coins is a craft dating back to the 18th century and today modified coins are known colloquially as hobo nickels. In the United States, especially during the Great Depression, coin engraving on the large-faced Indian Head nickel became a way to help make ends meet. The craft continues today, and with modern equipment often produces stunning miniature sculptural artworks and floral scrollwork.[8] During the mid-20th century, a renaissance in hand-engraving began to take place. With the inventions of pneumatic hand-engraving systems that aided hand-engravers, the art and techniques of hand-engraving became more accessible. Music engravingThe first music printed from engraved plates dates from 1446 and most printed music was produced through engraving from roughly 1700–1860. From 1860 to 1990 most printed music was produced through a combination of engraved master plates reproduced through offset lithography. The first comprehensive account is given by Mme Delusse in her article "Gravure en lettres, en géographie et en musique" in Diderot's Encyclopedia. The technique involved a five-pointed raster to score staff lines, various punches in the shapes of notes and standard musical symbols, and various burins and scorers for lines and slurs. For correction, the plate was held on a bench by callipers, hit with a dot punch on the opposite side, and burnished to remove any signs of the defective work. The process involved intensive pre-planning of the layout, and many manuscript scores with engraver's planning marks survive from the 18th and 19th centuries.[9]  By 1837 pewter had replaced copper as a medium, and Berthiaud gives an account with an entire chapter devoted to music (Novel manuel complet de l'imprimeur en taille douce, 1837). Printing from such plates required a separate inking to be carried out cold, and the printing press used less pressure. Generally, four pages of music were engraved on a single plate. Because music engraving houses trained engravers through years of apprenticeship, very little is known about the practice. Fewer than one dozen sets of tools survive in libraries and museums.[10] By 1900 music engravers were established in several hundred cities in the world, but the art of storing plates was usually concentrated with publishers. Extensive bombing of Leipzig in 1944, the home of most German engraving and printing firms, destroyed roughly half the world's engraved music plates. Applications todayExamples of contemporary uses for engraving include creating text on jewellery, such as pendants or on the inside of engagement- and wedding rings to include text such as the name of the partner, or adding a winner's name to a sports trophy. Another application of modern engraving is found in the printing industry. There, every day thousands of pages are mechanically engraved onto rotogravure cylinders, typically a steel base with a copper layer of about 0.1 mm in which the image is transferred. After engraving the image is protected with an approximately 6 μm chrome layer. Using this process the image will survive for over a million copies in high speed printing presses. Engraving machines such as GUN BOW (one of the leading engraving brands) are the best examples of hand engraving tools, although this type of machine is typically not used for fine hand engraving. Some schools throughout the world are renowned for their teaching of engraving, like the École Estienne in Paris. Creating tone In traditional engraving, which is a purely linear medium, the impression of half-tones was created by making many very thin parallel lines, a technique called hatching. When two sets of parallel-line hatchings intersected each other for higher density, the resulting pattern was known as cross-hatching. Patterns of dots were also used in a technique called stippling, first used around 1505 by Giulio Campagnola. Claude Mellan was one of many 17th-century engravers with a very well-developed technique of using parallel lines of varying thickness (known as the "swelling line") to give subtle effects of tone (as was Goltzius) – see picture below. One famous example is his Sudarium of Saint Veronica (1649), an engraving of the face of Jesus made from a single spiraling line that starts at the tip of Jesus's nose. Surface tone is achieved during the printing process, by selectively leaving a thin layer of ink on parts of the printing plate. Biblical referencesThe earliest allusion to engraving in the Bible may be the reference to Judah's seal ring (Ge 38:18), followed by (Ex 39.30). Engraving was commonly done with pointed tools of iron or even with diamond points. (Jer 17:1). Each of the two onyx stones on the shoulder-pieces of the high priest's ephod was engraved with the names of six different tribes of Israel, and each of the 12 precious stones that adorned his breastpiece was engraved with the name of one of the tribes. The holy sign of dedication, the shining gold plate on the high priest's turban, was engraved with the words: "Holiness belongs to Adonai." Bezalel, along with Oholiab, was qualified to do this specialized engraving work as well as to train others.—Ex 35:30–35; 28:9–12; 39:6–14, 30. Noted engravers Prints:

Of gems:

Of guns: Of coins: Of postage stamps: Of pins:

See also

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Engraving. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Engraved illustrations.

|