|

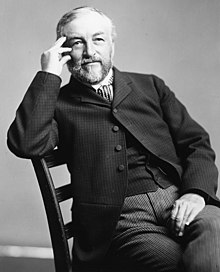

Samuel Langley

Samuel Pierpont Langley (August 22, 1834 – February 27, 1906) was an American aviation pioneer, astronomer and physicist who invented the bolometer. He was the third secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and a professor of astronomy at the University of Pittsburgh, where he was the director of the Allegheny Observatory. LifeLangley was born in Roxbury, Boston, on August 23, 1834.[3] Langley attended Boston Latin School and graduated from English High School of Boston, after which he became an assistant in the Harvard College Observatory. He then moved to a job at the United States Naval Academy, ostensibly as a professor of mathematics. However, he was actually sent there to restore the Academy's small observatory. In 1867, he became the director of the Allegheny Observatory and a professor of astronomy at the University of Pittsburgh (then known as the Western University of Pennsylvania), a post he kept until 1891 even while he became the third Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in 1887. Langley was the founder of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. In 1875, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[4] In 1888 Langley was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society.[5] In 1898, he received the Prix Jules Janssen, the highest award of the Société astronomique de France, the French astronomical society. Allegheny ObservatoryLangley arrived in Pittsburgh in 1867 to become the first director of the Allegheny Observatory, after the institution had fallen into hard times and been given to the Western University of Pennsylvania. By then, the department was in disarray – equipment was broken, there was no library and the building needed repairs. Through the friendship and aid of William Thaw Sr., a Pittsburgh industrial leader, Langley was able to improve the observatory equipment and build additional apparatuses. One of the new instruments was a small transit telescope used to observe the position of the stars as they cross the celestial meridian.[6] He raised money for the department in large part by distributing standard time to cities and railroads. Up until then, correct time had only occasionally been sent from American observatories for public use. Clocks were manually wound in those days and time tended to be imprecise. Exact time had not been especially necessary. It was enough to know that at noon the sun was at its highest elevation for the day. That changed with the arrival of railroads, which made the lack of standard time dangerous. Trains ran by a published schedule, but scheduling was chaotic. If the timepieces of an engineer and a switch operator differed by even a minute or two, trains could be on the same track at the same time and collide. Using astronomical observations obtained from the new telescope, Langley devised a precise time standard, including time zones, that became known as the Allegheny Time System. Initially he distributed time signals to Allegheny city businesses and the Pennsylvania Railroad. Eventually, twice a day, the Allegheny time signals gave the correct time via 4,713 miles of telegraph lines to all railroads in the US and Canada. Langley used the money from the railroads to finance the observatory. From about 1868 revenues from Allegheny Time continued to fund the observatory, until the US Naval Observatory provided the signals via taxpayer funding in 1883. Once funding was secure, Langley devoted his time at the Observatory initially in researching the sun. He used his draftsman skills—from his first job out of high school—to produce hundreds of drawings of solar phenomena, many of which were the first the world had seen. His remarkably detailed 1873 illustration of a sun spot, observed while using the observatory's 13-inch Fitz-Clark refractor became a classic. It is featured on page 21 of his book, The New Astronomy, and was also widely reprinted in the Americas and Europe. In 1886, Langley received the inaugural Henry Draper Medal from the National Academy of Sciences for his contributions to solar physics.[7] His publication in 1890 of infrared observations at the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh together with Frank Washington Very along with the data he collected from his invention, the bolometer, was used by Svante Arrhenius to make the first calculations on the greenhouse effect. In 1898, Langley received the Prix Jules Janssen, the highest award of the Société astronomique de France (the French astronomical society). Aviation work Langley attempted to make a working piloted heavier-than-air aircraft. His models flew, but his two attempts at piloted flight were not successful. Langley began experimenting with rubber-band powered models and gliders in 1887. (According to one book, he was not able to reproduce Alphonse Pénaud's time aloft with rubber power but persisted anyway.) He built a rotating arm that functioned like a wind tunnel, and made larger flying models powered by miniature steam engines. Langley realised that sustained powered flight was possible when he found that a 1 lb. brass plate suspended from the rotating arm by a spring, could be kept aloft by a spring tension of less than 1 oz. Langley understood that aircraft need thrust to overcome drag from forward speed, observed higher aspect ratio flat plates had higher lift and lower drag, and stated in 1902 "A plane of fixed size and weight would need less propulsive power the faster it flew", the counter-intuitive effect of induced drag.[8] He met the writer Rudyard Kipling around this time, who described one of Langley's experiments in his autobiography:

His first success came on May 6, 1896, when his Number 5 unpiloted model weighing 25 pounds (11 kg) made two flights – 2,300 ft (700 m) and 3,300 ft (1,000 m) – after a catapult launch from a boat on the Potomac River.[10][11] The distance was ten times longer than any previous experiment with a heavier-than-air flying machine,[12] demonstrating that stability and sufficient lift could be achieved in such craft.  On November 11 that year his Number 6 model flew more than 5,000 feet (1,500 m). In 1898, based on the success of his models, Langley received a War Department grant of $50,000 and $20,000 from the Smithsonian to develop a piloted airplane, which he called an "Aerodrome" (coined from Greek words roughly translated as "air runner"). Langley hired Charles M. Manly (1876–1927) as engineer and test pilot. When Langley received word from his friend Octave Chanute of the Wright brothers' success with their 1902 glider, he attempted to meet the Wrights, but they politely evaded his request.  While the full-scale Aerodrome was being designed and built, the internal combustion engine was contracted out to manufacturer Stephen M. Balzer (1864–1940). When he failed to produce an engine of the specified power and weight, Manly finished the design. This engine had far more power than did the engine for the Wright brothers' first airplane—50 hp compared to 12 hp. The engine, mostly the technical work of men other than Langley, was probably the project's main contribution to aviation.[13] The piloted machine had wire-braced tandem wings (one behind the other). It had a Pénaud tail for pitch and yaw control but no roll control, depending instead on the dihedral angle of the wings, as did the models, for maintaining roughly level flight.  In contrast to the Wright brothers' design of a controllable airplane that could fly with assistance from a strong headwind and land on solid ground, Langley sought safety by practicing in calm air over the Potomac River. This required a catapult for launching. The craft had no landing gear, the plan being to descend into the water after demonstrating flight which if successful would entail a partial, if not total, rebuilding of the machine.[14] Langley gave up the project after two crashes on take-off on October 7 and December 8, 1903. In the first attempt, Langley said the wing clipped part of the catapult, leading to a plunge into the river "like a handful of mortar," according to one reporter. On the second attempt the craft broke up as it left the catapult (Hallion, 2003; Nalty, 2003).[15] Manly was recovered unhurt from the river both times. Newspapers made great sport of the failures, and some members of Congress strongly criticized the project.  On 28 May 1914, the Aerodrome was modified and flown a few hundred feet by Glenn Curtiss, as part of his attempt to fight the Wright brothers' patent, and as an effort by the Smithsonian to rescue Langley's aeronautical reputation.[16] Nevertheless, courts upheld the patent. However, the Curtiss flights emboldened the Smithsonian to display the Aerodrome in its museum as "the first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight". Fred Howard, extensively documenting the controversy, wrote: "It was a lie pure and simple, but it bore the imprimatur of the venerable Smithsonian and over the years would find its way into magazines, history books, and encyclopedias, much to the annoyance of those familiar with the facts." (Howard, 1987). The Smithsonian's action triggered a decades-long feud with the surviving Wright brother, Orville, who objected to the Institution's claim of primacy for the Aerodrome. Unlike the Wright brothers with their invention of three-axis control, Langley had no effective way of controlling an airplane too big to be maneuvered by the weight of the pilot's body. So if the Aerodrome had flown stably, as the models did, Manly would have been in considerable danger when the machine descended, uncontrolled, for a landing—especially if it had wandered away from the river and over solid ground. BolometerIn 1880 Langley invented the bolometer, an instrument initially used for measuring far infrared radiation.[17] The bolometer has enabled scientists to detect a change of temperature of less than 1/100,000 of a degree Celsius.[18] It laid the foundation for the measurements of the amount of solar energy on the Earth. He published an 1881 paper on it, "The Bolometer and Radiant Energy".[19] He made one of the first attempts to measure the surface temperature of the Moon, and his measurement of interference of the infrared radiation by carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere was used by Svante Arrhenius in 1896 to make the first calculation of how climate would change from a future doubling of carbon dioxide levels.[20] Commercial time serviceStarting with his tenure at Allegheny Observatory in the Pittsburgh area in the late 1860s, Langley was a major player in the development of astronomically derived and regulated time distribution services in America through the later half of the 19th century. His work with the railroads in this area is often cited as central to the establishment of the Standard Time Zones system. His very successful and profitable time sales to the Pennsylvania Railroad stood out among the many non-government-based observatories of the day who were largely subsidizing their research by time-service sales to regional railroads and the cities they served. The United States Naval Observatory's increasing dominance in this field threatened these regional observatories' livelihoods and Langley became a leader in efforts to preserve the viability of their commercial programs. DeathLangley held himself responsible for the loss of funds after the June 1905 discovery that Smithsonian accountant William Karr was embezzling from the Institution. Langley refused his salary in the aftermath. In November he suffered a stroke. In February 1906 he moved to Aiken, South Carolina to recuperate, but had another stroke and died on February 27. He was buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston.[21] Legacy Air and sea craft, facilities, a unit of solar radiation, and an award have been named in Langley's honor, including:

In 1963, Langley was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in Dayton, Ohio.[24] MediaIn the 1978 film The Winds of Kitty Hawk, he was portrayed by actor John Hoyt. See alsoReferencesNotes

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Samuel Pierpont Langley.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||