|

Pre-Islamic Arabia

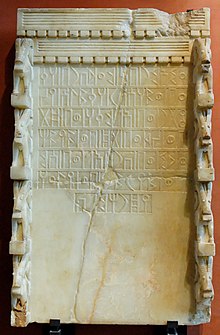

Pre-Islamic Arabia is the Arabian Peninsula and its northern extension in the Syrian Desert before the rise of Islam. This is consistent with how contemporaries used the term Arabia or where they said Arabs lived, which was not limited to the peninsula.[1] Pre-Islamic Arabia included both nomadic and settled populations. Several settled populations developed distinctive civilizations. From around the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE, Southern Arabia was the home to a number of kingdoms, such as the Sabaeans and the Minaeans, and Eastern Arabia was inhabited by Semitic-speaking peoples who presumably migrated from the southwest, such as the so-called Samad population.[2] From 106 CE to 630 CE, Arabia's most northwestern areas were controlled by the Roman Empire, which governed it as Arabia Petraea.[3] A few nodal points were controlled by the Iranian peoples, first under the Parthians and then under the Sasanians. Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia was diverse; although polytheism was prevalent for most of its history (especially in forms related to ancient Semitic religions), monotheism came to dominate in the region in the centuries leading up to the origins of Islam. There were also large pre-Islamic Christian and Jewish communities, especially in the north and south.[4] Sources of informationDetailed literary accounts from within pre-Islamic Arabia are absent. "There is no Arabian Tacitus or Josephus to furnish us with a grand narrative."[5] Information is synthesized from a diversity of sources, each potentially suffering from incompleteness, lateness, or bias. Islamic-era accounts represent oral traditions collected and codified during the Islamic period (including the Quran, pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, and Arabic histories). Contemporary information may come from archaeological excavations, pre-Islamic Arabian inscriptions, and literary accounts from observers beyond the peninsula (including by Assyrians, Babylonians, Israelites, Greeks, Romans, and Persians).[6][7] Coinage from South Arabia from the 4th century BCE to the 3rd century CE can inform knowledge of legend, iconography, and the history of rulership.[8] Large scale excavations on the peninsula are very recent, and so no firm chronology has been established for Arabian material culture.[9] The most advanced excavation work so far has been done in Eastern Arabia.[10] Eastern Arabia is also the earliest documented region in literary sources, as far back as 2500 BCE, with literary documentation of North and South Arabia beginning in 900 BCE.[11] Territorial definitionsThe word Arabia has been understood in many ways in ancient texts, but it was not a synonym for the Arabian Peninsula. In the earliest sources, Arabia was not the peninsula but the steppe and desert wastes bordering the states of Egypt and the Fertile Crescent. The early historian Herodotus applies the term to areas as far out as eastern Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Negev. Persian administrative lists refer to Arabâya as a place between Assyria and Egypt. According to Robert Hoyland, this is equivalent to Herodotus' Arabia plus areas of the Syrian desert. The Syrian Desert is what is meant by Pliny the Elder's "Arabia of the nomads".[1]  Eastern ArabiaEastern Arabia is a geographic region that generally refers to the territories covered by modern-day Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the east coast of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman.[11] The main language in this region among sedentary peoples was Aramaic, Arabic, and to some degree, Persian. The Syriac language also came to be spoken as a liturgical language.[12] Many religions were practiced in the area. Practitioners included Arab Christians (including the tribe of Abd al-Qays), Aramean Christians, Persian-speaking Zoroastrians[13] and Jewish agriculturalists.[14] One hypothesis holds that the contemporary Baharna are descendants of Arameans, Jews, and Persians from the area.[14][15] Zoroastrianism was also present in Eastern Arabia.[16][17][18] The Zoroastrians of Eastern Arabia were known as "Majoos" in pre-Islamic times.[19] The sedentary dialects of Eastern Arabia, including Bahrani Arabic, were influenced by Akkadian, Aramaic and Syriac languages.[20][21] Bronze Age (3000 – 1300 BCE) During the Bronze Age, most of Eastern Arabia was part of the land of Dilmun, including modern-day Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and the adjacent coast of Saudi Arabia. Its capital was located in Bahrain.[22] Dilmun is the earliest recorded civilization from Eastern Arabia, mentioned in written records in the 3rd millennium BCE,[22] with archaeological evidence indicating activity from the fourth to first millennia BCE, its importance faltering after 1800.[23][24] Dilmun is regarded as one of the oldest ancient civilizations in the Middle East in general.[25][26] The Dilmun civilization was an important trading center[23] which at the height of its power controlled the Persian Gulf trading routes.[23] This was enabled by a number of natural advantages to the region, and part of this was its abundant underground water supplies and easy anchorages for ships. It became a center for long-distance trade and all types of commodities passed through it (trade extending to areas as far as the Indus Valley[26]), including a variety of exotic goods. As a result, Dilmun became legendary in Mesopotamian literature.[22] The Sumerians regarded Dilmun as holy land.[27] The Sumerians described Dilmun as a paradise garden in the Epic of Gilgamesh.[28] The Sumerian tale of the garden paradise of Dilmun may have been an inspiration for the Garden of Eden story.[28] Dilmun, sometimes described as "the place where the sun rises" and "the Land of the Living", is the scene of some versions of the Eridu Genesis, and the place where the deified Sumerian hero of the flood, Utnapishtim (Ziusudra), was taken by the gods to live forever. Thorkild Jacobsen's translation of the Eridu Genesis calls it "Mount Dilmun" which he locates as a "faraway, half-mythical place".[29] Dilmun was mentioned in two letters dated to the reign of Burna-Buriash II (c. 1370 BCE) recovered from Nippur, during the Kassite dynasty of Babylon. These letters were from a provincial official, Ilī-ippašra, in Dilmun to his friend Enlil-kidinni in Mesopotamia. The names referred to are Akkadian. These letters and other documents, hint at an administrative relationship between Dilmun and Babylon at that time. Following the collapse of the Kassite dynasty, Mesopotamian documents make no mention of Dilmun with the exception of Assyrian inscriptions dated to 1250 BCE which proclaimed the Assyrian king to be king of Dilmun and Meluhha. Assyrian inscriptions recorded tribute from Dilmun. There are other Assyrian inscriptions during the first millennium BCE indicating Assyrian sovereignty over Dilmun.[30] Dilmun was also later on controlled by the Kassite dynasty in Mesopotamia.[31] In 19th and early 20th centuries, some historians believed that the Phoenicians originated from Eastern Arabia, particularly Dilmun. However, this theory has since been abandoned.[32] Iron Age (1300 – 330 BCE)Upon the Late Bronze Age collapse, the major powers across the Near East lost much of their power and this allowed many smaller and far-flung states to become more independent and a number of minor states to emerge. In addition, new scripts and alphabets were developed, which were of great utility to merchants for producing contracts and conducting other and related economic affairs. In turn, the Middle Assyrian Empire became much more prominent and undertook an aggressively expansionist policy. In the second half of the 13th century BCE, Tukulti-Ninurta I took on the title "king of Dilmun and Meluhha". Dilmun disappears from Assyrina sources until the reign of Sargon II, king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Here and across the next century, Dilmun appears as a polity that is not directly ruled by Assyria, although it sends tribute to the Assyrian rulers in exchange for peace and independence. When the Neo-Babylonian Empire overthrew the Assyrian Empire, its influence on Dilmun is also attested. Finally, Dilmun falls under the sway of the Persians after the rise of the Achaemenid Empire which replaces the Babylonian one.[33] Greco-Roman/Parthian period (330 BCE – 240 CE)After Alexander the Great returned from his conquests that reached India, settling in Babylonia, it is said by the historian Arrian that he was turning his attention towards an invasion of the Arabian peninsula. Although he died too soon for this campaign to take place, Alexander did dispatch three intelligence-gathering missions to gather knowledge about the peninsula, and it was these missions that greatly enhanced information about the peninsula to the Hellenistic world. Alexander, and his Seleucid successors who took control of the relevant region near Arabia after his death, took an interest to Arabia because of trade happening there involving luxury products.[34]  In this context, Gerrha was an ancient city of great importance in Eastern Arabia. It was located on the west side of the Persian Gulf. Soon after the conquests of Alexander the Great, it became the most important center of trader for the Hellenistic world in the Gulf region, known for its transport of Arabian aromatics and goods from India further away. It retained its prominence until the first centuries of the common era.[35] While there is no certainty as to which archaeological site the Gerrha of Greek sources can be identified with, the most prominent candidates have been Thaj and Hagar (modern-day Hofuf).[36] The Greeks also described Bahrain in their writings, referring to it by their exonym, Tylos. Tylos was the center of pearl trading, when Nearchus came to discover it serving under Alexander the Great.[37] From the 6th to 3rd century BCE Bahrain was included in Persian Empire by Achaemenians, an Iranian dynasty.[38] The Greek admiral Nearchus is believed to have been the first of Alexander's commanders to visit this islands, and he found a verdant land that was part of a wide trading network; he recorded: "That in the island of Tylos, situated in the Persian Gulf, are large plantations of cotton tree, from which are manufactured clothes called sindones, a very different degrees of value, some being costly, others less expensive. The use of these is not confined to India, but extends to Arabia."[39] The Greek historian, Theophrastus, states that much of the islands were covered in these cotton trees and that Tylos was famous for exporting walking canes engraved with emblems that were customarily carried in Babylon.[40] It is not known whether Bahrain was part of the Seleucid Empire, although the archaeological site at Qalat Al Bahrain has been proposed as a Seleucid base in the Persian Gulf.[41] Tylos was integrated well into the Hellenised world: the language of the upper classes was Greek (although Aramaic was in everyday use), while Zeus was worshipped in the form of the Arabian sun-god Shams.[42] Tylos even became the site of Greek athletic contests.[43] Another important player in this time was the Parthian Empire, which emerged from northeastern Iran and relinquished a significant amount of territory from the eastern borders of the Seleucids. The Seleucids would be eventually vanquished by the Roman Empire over the course of the 1st century BCE, leading to the Romans and Parthians being the main power contenders in the region, separated by the Syrian desert.[44] Parthian influence extended over the Persian Gulf and reached as far as Oman. Garrisons were established at the southern coast of the Gulf to help extend their power.[45] Byzantine/Sasanian period (240 CE – 630 CE) A major shift in dynamics accompanied the replacement of the Parthian dynasty in Persian lands by the Sasanians, leading to the rise of the Sasanian Empire around 240 CE. Seizing the moment, Ardashir I, the first ruler of this dynasty marched down the Persian Gulf to Oman and Bahrain and defeated Sanatruq[46] (or Satiran[38]), probably the Parthian governor of Eastern Arabia.[47] He appointed his son Shapur I as governor of Eastern Arabia. Shapur constructed a new city there and named it Batan Ardashir after his father.[38] At this time, Eastern Arabia incorporated the southern Sasanian province covering the Persian Gulf's southern shore plus the archipelago of Bahrain.[47] The southern province of the Sasanians was subdivided into the three districts of Haggar (Hofuf, Saudi Arabia), Batan Ardashir (al-Qatif province, Saudi Arabia), and Mishmahig (Muharraq, Bahrain; also referred to as Samahij)[38] which included the Bahrain archipelago that was earlier called Aval.[38][47] Sasanian interests in the region largely lay in controlling traffic through the Persian Gulf, but land-incursions into the peninsula were occasionally undertaken, such as when the inhabitants of Eastern Arabia invaded southern Iran during the reign of Shapur II in the fourth century CE. During the political struggles of the sixth century, Khosrow I began to exert more direct rule over Eastern Arabia, including the direct appointment of regional governors. Another development of the Sasanian period is the rise of Christianity in Eastern Arabia.[48] Beth QatrayeIn antiquity, Syriac Christians referred to a region in northeast Arabia as Beth Qatraye, or the "region of the Qataris". This region encompassed a territory that, today, includes Bahrain, Tarout Island, Al-Khatt, Al-Hasa, Qatar, and possibly the United Arab Emirates.[49] The region was also sometimes called "the Isles".[50] By the 5th century, Beth Qatraye was a major centre for Nestorian Christianity, which had come to dominate the southern shores of the Persian Gulf.[51][52] As a sect, the Nestorians were often persecuted as heretics by the Byzantine Empire, but eastern Arabia was outside the Empire's control offering some safety. Several notable Nestorian writers originated from Beth Qatraye, including Isaac of Nineveh, Dadisho Qatraya, Gabriel of Qatar and Ahob of Qatar.[51][53] Christianity's significance was diminished by the arrival of Islam in Eastern Arabia by 628.[54] In 676, the bishops of Beth Qatraye stopped attending synods; although the practice of Christianity persisted in the region until the late 9th century.[51] The dioceses of Beth Qatraye did not form an ecclesiastical province, except for a short period during the mid-to-late seventh century.[51] They were instead subject to the Metropolitan of Fars. Beth MazunayeOman and the United Arab Emirates comprised the ecclesiastical province known as Beth Mazunaye. The name was derived from 'Mazun', the Persian name for Oman and the United Arab Emirates.[50] South ArabiaSouth Arabia roughly corresponds to modern-day Yemen, with Oman being designated as part of Eastern Arabia.[11] In contrast to the rest of Arabia, South Arabia is a self-contained cultural area that retained the independence of its cultural, political, and linguistic dynamics from the rise of its first known kingdoms until the end of Late Antiquity.[55] The rise of the South Arabian kingdoms owes itself to the construction of irrigation complexes that captured precipitation by the biannual monsoon rains, enabling agriculture, and the trade routes that carried incense and other spices, giivng rise to tales of legendary wealth about the region among Greco-Roman observers.[56] The South Arabian kingdoms emerged in the early first millennium BCE, and they included the Kingdoms of Ma'in, Saba, Hadhramaut, Aswan, and Qataban. Until recently, very little was known about human activity in South Arabia prior to the first millennium BCE. However, recent decades of archaeological work have begun to rapidly change this situation.[57] This has helped increase the prominence of the discipline, though it has not yet became a mainstream topic in Near Eastern archaeology.[58] In the third century CE, the Kingdom of Himyar emerged and conquered its neighbours to exert complete political domination over South Arabia. This situation persisted for several centuries, until the Himyarite polity unravelled over the course of the sixth century CE and experienced a societal collapse. The exact cause is not definitively known, but there is evidence that coinciding events helped cause this situation. Epidemically, an inscription from the 550s about an illness indicates that the Plague of Justinian struck the area. Militarily, the Aksumite invasion of Himyar fragmented contributed to the fragmentation of existing political structures. Severe climactic changes are also known from this time. These included the abrupt appearance of severe droughts from about 500 to 530 CE, and the appearance of the Late Antique Little Ice Age in the years approaching the mid-6th century. Different regions of Arabia were impacted in different ways, but the bulk of the effect was in the South, and there, especially the Southwest. By the 550s and 560s, Himyar's decline was completed, as it faced military incursions from Central and Northwest Arabia, as well as insurrections from home. In 559 CE, the final Himyarite inscription was recorded. The collapse of the traditional order is indicated by the breakdown of the Marib Dam over the course of the 570s. A creeping in of influence from the Persian Sasanian Empire is evident towards the end of the 6th century.[59][60]   Kingdom of Saba (1000 BCE – 275 CE)The Kingdom of Saba (or Sheba) was regarded by the South Arabian and earliest Ethiopian kingdoms as the locus for the birth of South Arabian civilization.[61] The kingdom spoke Sabaic and constructed many impressive architectural complexes, such as the Marib Dam, which helped sequester the monsoon rains through an irrigation network that laid the foundation for the emergence of a civilization, and many temples, including the Temple of Awwam for their national god Almaqah where hundreds of inscriptions have been discovered.[62] The Sabaeans had close contact with the cultures of the Horn of Africa. They went on to conquer both Eritrea and northern Ethiopia to establish the Kingdom of Dʿmt, where a hybrid Ethiosemitic script emerged.[63][64][65] Under the leadership of Karib'il Watar, Saba dominated most of modern-day Yemen, a feat that would not be accomplished again in the region until the Himyarite Kingdom a thousand years later. Their legacy was remembered in both biblical and Islamic tradition, especially in the legendary story of the Queen of Sheba.[66] The Sabaean kingdom emerged some time around the turn of the 1st millennium BCE. By the time that the formative period of Sabaean history was complex, a fully developed alphabetic script was available, as well as the technological prowess to construct cities and other architectural complexes. There is some debate as to the degree to which the movement out of the formative phase was channeled by endogenous processes, or the transfer or technologies from other centers, perhaps via trade and immigration.[67][68] The first major phase of Sabaean civilization lasted from the 8th to the 1st centuries BCE. Rulers referred to themselves by the title Mukarrib ("federator") as a testimony to the hegemony they exerted over neighbouring polities.[69] The period was dominated by a caravan economy that had market ties with the rest of the Near East. Its first major trading partners were at Khindanu and the Middle Euphrates. Later, this moved to Gaza during the Persian period, and finally, to Petra in Hellenistic times. The South Arabian deserts gave rise to important aromatics which were exported in trade, especially frankincense and myrrh. It also acted as an intermediary for overland trade with neighbours in Africa and further off from India. Saba was a theocratic monarchy with a common cult surrounding their national god, Almaqah. Four other deities were also worshipped: Athtar, Haubas, Dhat-Himyam, and Dhat-Badan.[70] The first Sabaean period came to a close as the Roman Republic expanded to conquer Syria and Egypt in 63 and 30 BCE, respectively. They diverted the overland trade route through the Sabaean kingdom into a maritime trade route that went through the Hadhramaut port city of Qani. They even attempted to siege Marib, the Sabaean capital, but were unsuccessful. Greatly weakened, they were annexed by the neighbouring Himyarite Kingdom.[71][72] Saba was able to regain their independence around 100 CE to onset a second period of their civilization. Notably, power dynamics had shifted from oasis cities like Marib and Sirwah to groups occupying the highlands. Ultimately, Himyar permanently re-annexed them, around 275 CE.[72] Kingdom of Awsan (8th century BCE – 7th century BCE)Awsan was a South Arabian kingdom that lasted from the 8th to 7th centuries BCE, with a brief resurgence in the 2nd or 1st century BCE. Awsan is centered around a wadi called the Wadi Markha. The name of the capital of Awsan is unknown, but it is assumed to be the tell that is today known as Hagar Yahirr, the largest settlement in the wadi. The territory under its control was sizable enough that it was a powerful contender in local power politics. In the late 7th century BCE, under the reign of its ruler Murattaʿ, Awsan entered a military conflict with the Kingdom of Saba that brought about its demise. The Sabaean king, Karib'il Watar, defeated Awsan and proceeded to obliterate it. An inscription left behind claims that Karib'il killed over 16,000 people and took 40,000 more as prisoners. After this event, the wadi was left abandoned, and Awsan disappeared from the historical record for the time being.[73] Saba had divided its territory between its then-allies, Qataban and Hadhramaut. Half a millennium later, when Qataban's control over the Wadi Markha was declining, Awsan was able to briefly re-emerge, in the 2nd or 1st centuries BCE. This final phase of the Awsanite kingdom is the only period in South Arabian history where kings were deified.[74] Kingdom of Ma'in (8th century BCE – 1st century CE)The Minaeans, or the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Ma'in, had their capital at Qarna (modern-day Sa'dah). Another important city was Yathill (now known as Baraqish). The Minaean Kingdom was centered in northwestern Yemen, with most of its cities lying along Wādī Madhab. Ma'in was responsible for managing an international frankincense trade and it set up a number of colonies across Arabia and the Mediterranean to manage it. For this reason, Minaic inscriptions have been found far afield of the Kingdom of Maīin, as far away as al-'Ula in northwestern Saudi Arabia and even on the island of Delos and Egypt.[75][76] Kingdom of Qataban (8th century BCE – 2nd century CE)Qataban was one of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms which thrived in the Beihan valley. Like the other Southern Arabian kingdoms, it gained great wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense, which were burned at altars. The capital of Qataban was named Timna and was located on the trade route which passed through the other kingdoms of Hadramaut, Saba and Ma'in. The chief deity of the Qatabanians was Amm, or "Uncle" and the people called themselves the "children of Amm". Kingdom of Hadhramaut (8th century BCE – 3rd century CE)Hadhramaut is first mentioned in a 7th century BCE inscription from the king of the Sabaean kingdom, Karib'il Watar, mentioned as an ally. For commercial reasons, Hadhramaut became one of the confederates of Ma'in when they took control of the caravan routes. After the fall of Ma'in, it experienced a period of independence. Hadhramaut had to repel attacks by Himyar in the 1st century BCE, and managed to annex Qataban in the 2nd century CE, when it reached its greatest size. Ultimately, the kingdom did fall to an invasion by the Himyarite king Shammar Yahri'sh in the 3rd century CE, making it the final one of the South Arabian kingdoms to fall to Himyar.[77] Kingdom of Himyar (110 BCE – 530 CE) Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to classical sources, their capital was the ancient city of Zafar, relatively near the modern-day city of Sana'a. Himyarite power eventually shifted to Sana'a as the population increased in the fifth century. After the establishment of their kingdom, it was ruled by kings from dhū-Raydān tribe. The kingdom was named Raydān.[78] The kingdom conquered neighbouring Saba' in c. 25 BCE (for the first time), Qataban in c. 200 CE, and Haḍramaut c. 300 CE. Its political fortunes relative to Saba' changed frequently until it finally conquered the Sabaean Kingdom around 280.[79] With successive invasion and Arabization, the kingdom collapsed in the early sixth century, as the Kingdom of Aksum conquered it in 530 CE.[80][81] The Himyarites originally worshiped most of the South-Arabian pantheon, including Wadd, ʿAthtar, 'Amm and Almaqah. Since at least the reign of Malkikarib Yuhamin (c. 375–400 CE), Judaism was adopted as the de facto state religion. The religion may have been adopted to some extent as much as two centuries earlier, but inscriptions to polytheistic deities ceased after this date. It was embraced initially by the upper classes, and possibly a large proportion of the general population over time.[78] Native Christian kings ruled Himyar in 500 CE until 521–522 CE as well, Christianity itself became the main religion after the Aksumite conquest in 530 CE.[82][83][84]  Aksumite occupation of Yemen (525 – 570 CE)In response to the massacre of the Christian community of Najran under the reign of the Jewish king Dhu Nuwas, the Christian king of the Kingdom of Aksum, Kaleb, responded by invading and annexing Himyar. Sasanian period (570 – 630 CE)The Persian king Khosrau I sent troops under the command of Vahriz (Persian: اسپهبد وهرز), who helped the semi-legendary Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan to drive the Aksumites out of Yemen. Southern Arabia became a Persian dominion under a Yemenite vassal and thus came within the sphere of influence of the Sasanian Empire. After the demise of the Lakhmids, another army was sent to Yemen, making it a province of the Sasanian Empire under a Persian satrap. Following the death of Khosrau II in 628, the Persian governor in Southern Arabia, Badhan, converted to Islam and Yemen followed the new religion. Western Arabia (Hejaz)  Kingdom of Lihyan/Dedan (5th century BCE - 1st century BCE)Lihyan, also called Dedan, was a northwestern kingdom whose language was Dadanitic. The kingdom existed sometime between the 5th and 1st centuries BCE, but the end-date is uncertain. It is unclear if Lihyan was conquered by the Nabataeans or if the Nabataeans captured the territory after Lihyan had already fallen.[85] ThamudThe Thamud (Arabic: ثمود) was an ancient civilization in Hejaz, documented in sources from the eighth century BCE until the fifth century CE. They are attested in contemporaneous Mesopotamian and Classical, and Arabic inscriptions from the eighth century BCE, all the way until the fifth century CE, when they served as Roman auxiliaries. They are also later remembered in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry and Islamic-era sources, including the Quran. Prominently, they appear in the Ruwafa inscriptions discovered in a temple constructed circa 165–169 CE in honor of the local deity, ʾlhʾ. Thamud appears twenty-six times in the Quran where the tribe is presented as an example of an ancient polytheistic people destroyed by God for their rejection of God's prophet Salih.[86] Thamud is associated in the Quran into its grander history of a pattern of rebellion and destruction of past groups of people. This is done the most times with Ad, but others as well like Lot and Noah. When Salih calls Thamud to serve one God, they demand a sign from him. He presents them with a miraculous she-camel. Thamud, unconvinced, injures the camel: for this God destroys them, except Salih and his followers. This account is embellished with a more detailed background in the Islamic exegetical tradition. Some traditions locate them in northwestern Arabia at Hegra and in others they are identified as Nabataeans.[87] Islamic genealogy describes the Thamud as among the true Arab tribes, as opposed to the "Arabicized Arabs".[88] North Arabia Kingdom of Qedar (8th century BCE – ?)The most organized of the Northern Arabian tribes, at the height of their rule in the 6th century BCE, the Kingdom of Qedar spanned a large area between the Persian Gulf and the Sinai.[90] An influential force between the 8th and 4th centuries BCE, Qedarite monarchs are first mentioned in inscriptions from the Assyrian Empire. Some early Qedarite rulers were vassals of that empire, with revolts against Assyria becoming more common in the 7th century BCE. It is thought that the Qedarites were eventually subsumed into the Nabataean state after their rise to prominence in the 2nd century CE. The Achaemenids in Northern ArabiaAchaemenid Arabia corresponded to the lands between Nile Delta (Egypt) and Mesopotamia, later known to Romans as Arabia Petraea. According to Herodotus, Cambyses did not subdue the Arabs when he attacked Egypt in 525 BCE. His successor Darius the Great does not mention the Arabs in the Behistun inscription from the first years of his reign, but does mention them in later texts. This suggests that Darius might have conquered this part of Arabia[91] or that it was originally part of another province, perhaps Achaemenid Babylonia, but later became its own province. Arabs were not considered as subjects to the Achaemenids, as other peoples were, and were exempt from taxation. Instead, they simply provided 1,000 talents of frankincense a year. They participated in the Second Persian invasion of Greece (479-480 BCE) while also helping the Achaemenids invade Egypt by providing water skins to the troops crossing the desert.[92] Nabateans The Nabataeans are not to be found among the tribes that are listed in Arab genealogies because the Nabatean kingdom ended a long time before the coming of Islam. They settled east of the Syro-African rift between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea, that is, in the land that had once been Edom. And although the first sure reference to them dates from 312 BCE, it is possible that they were present much earlier. Petra (from the Greek petra, meaning 'of rock') lies in the Jordan Rift Valley, east of Wadi `Araba in Jordan about 80 km (50 mi) south of the Dead Sea. It came into prominence in the late 1st century BCE through the success of the spice trade. The city was the principal city of ancient Nabataea and was famous above all for two things: its trade and its hydraulic engineering systems. It was locally autonomous until the reign of Trajan, but it flourished under Roman rule. The town grew up around its Colonnaded Street in the 1st century and by the middle of the 1st century had witnessed rapid urbanization. The quarries were probably opened in this period, and there followed virtually continuous building through the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. Roman ArabiaThere is evidence of Roman rule in northern Arabia dating to the reign of Caesar Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE). During the reign of Tiberius (14–37 CE), the already wealthy and elegant north Arabian city of Palmyra, located along the caravan routes linking Persia with the Mediterranean ports of Roman Syria and Phoenicia, was made part of the Roman province of Syria. The area steadily grew further in importance as a trade route linking Persia, India, China, and the Roman Empire. During the following period of great prosperity, the Arab citizens of Palmyra adopted customs and modes of dress from both the Iranian Parthian world to the east and the Graeco-Roman west. In 129, Hadrian visited the city and was so enthralled by it that he proclaimed it a free city and renamed it Palmyra Hadriana.  The Roman province of Arabia Petraea was created at the beginning of the 2nd century by emperor Trajan. It was centered on Petra, but included even areas of northern Arabia under Nabatean control. Recently evidence has been discovered that Roman legions occupied Mada'in Saleh in the Hijaz mountains area of northwestern Arabia, increasing the extension of the "Arabia Petraea" province.[93] The desert frontier of Arabia Petraea was called by the Romans the Limes Arabicus. As a frontier province, it included a desert area of northeastern Arabia populated by the nomadic Saraceni. Later politiesCentral ArabiaKingdom of KindahKindah was an Arab kingdom by the Kindah tribe, the tribe's existence dates back to the second century BCE.[94] The Kindites established a kingdom in Najd in central Arabia unlike the organized states of Yemen; its kings exercised an influence over a number of associated tribes more by personal prestige than by coercive settled authority. Their first capital was Qaryat Dhāt Kāhil, today known as Qaryat Al-Fāw.[95] Ancient South Arabian inscriptions mention a tribe settling in Najd called kdt, who had a king called rbˁt (Rabi'ah) from ḏw ṯwr-m (the people of Thawr), who had sworn allegiance to the king of Saba' and Dhū Raydān.[96] Since later Arab genealogists trace Kindah back to a person called Thawr ibn 'Uqayr, modern historians have concluded that this rbˁt ḏw ṯwrm (Rabī'ah of the People of Thawr) must have been a king of Kindah (kdt); the Musnad inscriptions mention that he was king both of kdt (Kindah) and qhtn (Qaḥṭān). They played a major role in the Himyarite-Ḥaḑramite war. Following the Himyarite victory, a branch of Kindah established themselves in the Marib region, while the majority of Kindah remained in their lands in central Arabia. The first Classical author to mention Kindah was the Byzantine ambassador Nonnosos, who was sent by the Emperor Justinian to the area. He refers to the people in Greek as Khindynoi (Greek Χινδηνοι, Arabic Kindah), and mentions that they and the tribe of Maadynoi (Greek: Μααδηνοι, Arabic: Ma'ad) were the two most important tribes in the area in terms of territory and number. He calls the king of Kindah Kaïsos (Greek: Καισος, Arabic: Qays), the nephew of Aretha (Greek: Άρεθα, Arabic: Ḥārith). Genealogical tradition Arab traditions relating to the origins and classification of the Arabian tribes is based on biblical genealogy. The general consensus among 14th-century Arab genealogists was that Arabs were three kinds:

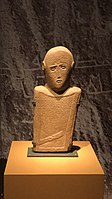

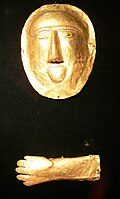

Modern historians believe that these distinctions were created during the Umayyad period, to support the cause of different political factions.[97] Religion Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia included pre-Islamic Arabian polytheism, ancient Semitic religions, and Abrahamic religions such as Christianity and Judaism. Other religions that may have existed in pre-Islamic Arabia are Samaritanism, Mandaeism, and Iranian religions like Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism. Arabian polytheism was, according to Islamic tradition, the dominant form of religion in pre-Islamic Arabia, based on veneration of deities and spirits. Worship was directed to various gods and goddesses, including Hubal and the goddesses al-Lāt, Al-'Uzzá and Manāt, at local shrines and temples, maybe such as the Kaaba in Mecca. Deities were venerated and invoked through a variety of rituals, including pilgrimages and divination, as well as ritual sacrifice. Different theories have been proposed regarding the role of Allah in Meccan religion. Many of the physical descriptions of the pre-Islamic gods are traced to idols, especially near the Kaaba, which is said to have contained up to 360 of them in Islamic tradition. Other religions were represented to varying, lesser degrees. The influence of the adjacent Roman and Aksumite resulted in Christian communities in the northwest, northeast and south of Arabia. Christianity in pre-Islamic Arabia made a lesser impact, but secured some conversions, in the remainder of the peninsula. With the exception of Nestorianism in the northeast and the Persian Gulf, the dominant form of Christianity was Miaphysitism. The peninsula had been a destination for Jewish migration since pre-Roman times, which had resulted in a diaspora community supplemented by local converts. Additionally, the influence of the Sasanian Empire resulted in Iranian religions being present in the peninsula. While Zoroastrianism existed in the eastern and southern Arabia, there was no existence of Manichaeism in Mecca.[100][101] From the fourth-century onwards, monotheism became increasingly prevalent in pre-Islamic Arabia, as is attested in texts like the inscriptions from Jabal Dabub, Ri al-Zallalah, and the Abd Shams inscription.[102] LiteracyAccording to a classification system for understanding literary in pre-Islamic Arabia established by Michael C.A. MacDonald, societies where writing is used can be divided into literate and non-literate societies, depending on the role that writing played within the functioning of the society. A nonliterate society is one where the ability to write is widespread without any place allocated for writing in the administration of a society (in the use of official inscriptions, legal contracts, etc). By contrast, a literate society relies on writing for the administrative functioning of a society.[103] Literacy was widespread in pre-Islamic Arabia among both nomads and settled peoples. Nomadic Arab societies in northern Arabia and the southern Levant are classified as non-literate. This is because, while the capacity for writing was common among individuals in these populations, writing itself was primarily used for entertainment and passing the time as opposed to administrative or legal utility. South Arabia was a literate society, as indicated by the discovery of thousands of public inscriptions. The presence of thousands of graffiti also suggest that writing was widespread among the common people and not just the upper echelon. The major oases towns in North and West Arabia were also literate societies.[104][105] HellenizationHellenization refers to the mixing between local cultures with the Greco-Roman culture that was spread in the aftermath of the conquests of Alexander the Great. Hellenization is believed to have spread into pre-Islamic Arabian culture.[106] The earliest evidence of Hellenistic contact in the Arabian peninsula goes back to the 3rd century BC, but at this time, it is only occurring in Eastern Arabia, as shown by the amphorae from Rhodes and Chios. In South Arabia, Hellenization reaches Arabia by the 2nd or 1st centuries BC. This can be seen in the last of the kings of Qataban, who reigned around this time.[107] In the resurgent period of the South Arabian Kingdom of Awsan, during the 2nd or 1st centuries BC, an evolution of the iconography of the kings is seen: they are transformed from wearing traditional South Arabian clothing to being shown dressed as a Roman citizen would, with curly hair and wearing a toga.[74] At the Kingdom of Saba, the traditional Near Eastern norms of iconographic depictions of the gods give way to Roman and Hellenistic anthropomorphic styles around the turn of the Christian era.[108] Recently, Latin inscriptions have revealed a Roman military presence as far south as the Farasan Islands, in southwestern Saudi Arabia.[109] In 106 AD, the Roman Empire conquered the northwest Arabian Nabataean Kingdom and they set up a province called Arabia Petraea (Roman Arabia). By this time, Roman rule had already long been imposed on Arabic-speaking populations in Syria, the Transjordan, and Palestine. The new conquests had extended this rule to northwest Arabia, including the northern parts of the Hejaz.[106] Archaeological finds of Roman military encampments have been made at Hegra (Mada'in Salih), located today in the Medina Province of Saudi Arabia, and at Ruwafa, as shown by the second-century Greek-Arabic bilingual Ruwafa inscriptions.[110] The Letter of the Archimandrites dating to 569/570, composed in Greek but preserved in Syriac, demonstrating the presence and distribution of episcopal sees from its 137 Archimandrite signatories from the province of Roman Arabia.[111] Safaitic inscriptions mention the Roman emperor. Arabic-speaking tribes were gradually converting to Christianity or becoming foederati of the emperor, resulting in increasing integration into the Roman world over time. In the mid-sixth century, for example, Justinian I was closely allied with the Ghassanids, a Hellenized Christian Arab kingdom.[106] In Central Arabia, statues of Greek deities like Artemis, Heracles, and Harpocrates have been discovered have been found at Qaryat al-Faw, the former capital of the Kingdom of Kinda.[106] Hellenization is also seen in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry.[112] ArtThe art is similar to that of neighbouring cultures. Pre-Islamic Yemen produced stylized alabaster (the most common material for sculpture) heads of great aesthetic and historic charm.

Late Antiquity

The early 7th century in Arabia began with the longest and most destructive period of the Byzantine–Sasanian Wars. It left both the Byzantine and Sasanian empires exhausted and susceptible to third-party attacks, particularly from nomadic Arabs united under a newly formed religion. According to historian George Liska, the "unnecessarily prolonged Byzantine–Persian conflict opened the way for Islam".[113] The demographic situation also favoured Arab expansion: overpopulation and lack of resources encouraged Arabs to migrate out of Arabia.[114] Fall of the EmpiresBefore the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, the Plague of Justinian had erupted (541–542), spreading through Persia and into Byzantine territory. The Byzantine historian Procopius, who witnessed the plague, documented that citizens died at a rate of 10,000 per day in Constantinople.[115] The exact number; however, is often disputed by contemporary historians. Both empires were permanently weakened by the pandemic as their citizens struggled to deal with death as well as heavy taxation, which increased as each empire campaigned for more territory. Despite almost succumbing to the plague, Byzantine emperor Justinian I (reigned 527–565) attempted to resurrect the might of the Roman Empire by expanding into Arabia. The Arabian Peninsula had a long coastline for merchant ships and an area of lush vegetation known as the Fertile Crescent which could help fund his expansion into Europe and North Africa. The drive into Persian territory would also put an end to tribute payments to the Sasanians, which resulted in an agreement to give 11,000 lb (5,000 kg) of tribute to the Persians annually in exchange for a ceasefire.[116] However, Justinian could not afford further losses in Arabia. The Byzantines and the Sasanians sponsored powerful nomadic mercenaries from the desert with enough power to trump the possibility of aggression in Arabia. Justinian viewed his mercenaries as so valued for preventing conflict that he awarded their chief with the titles of patrician, phylarch, and king – the highest honours that he could bestow on anyone.[117] By the late 6th century, an uneasy peace remained until disagreements erupted between the mercenaries and their patron empires. The Byzantines' ally was a Christian Arabic tribe from the frontiers of the desert known as the Ghassanids. The Sasanians' ally; the Lakhmids, were also Christian Arabs, but from what is now Iraq. However, denominational disagreements about God forced a schism in the alliances. The Byzantines' official religion was Orthodox Christianity, which believed that Jesus Christ and God were two natures within one entity.[118] The Ghassanids, as Monophysite Christians from Iraq, believed that God and Jesus Christ were only one nature.[119] This disagreement proved irreconcilable and resulted[when?] in a permanent break in the alliance. Meanwhile, the Sasanian Empire broke its alliance with the Lakhmids due to false accusations that the Lakhmids' leader had committed treason; the Sasanians annexed the Lakhmid kingdom in 602.[120] The fertile lands and important trade routes of Iraq were now open ground for upheaval. Rise of Islam Prophet Muhammad, 622–632 Rashidun Caliphate, 632–661 Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750 When the military stalemate was finally broken and it seemed that Byzantium had finally gained the upper hand in battle, nomadic Arabs invaded from the desert frontiers, bringing with them a new social order that emphasized religious devotion over tribal membership. The political apparatus created by Muhammad (d. 632) was able to conquer Arabia within a few years of his death. Afterwards, this group invaded the Near East into both Sasanian and Byzantine territory. Within a few decades, the Sasanian empire had fallen entirely, with Byzantine territories in the Levant, the Caucasus, Egypt, Syria and North Africa also taken.[113][need quotation to verify] By the end of the seventh century, an empire stretching from the Pyrenees Mountains in Europe to the Indus River valley in South Asia had been established.[121] See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to Pre-Islamic Arabia. Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Pre-Islamic Arabia.

Notes

Bibliography

Further reading

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||