|

Pacifism in Islam

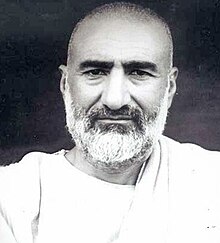

Different Muslim movements through history had linked pacifism with Muslim theology.[1][2][3] However, warfare has been an integral part of Islamic history both for the defense and the spread of the faith since the time of Muhammad.[4][5][6][7] Peace is an important aspect of Islam, and Muslims are encouraged to strive for peace and peaceful solutions to all problems. However, the teachings in the Qur'an and Hadith allow for wars to be fought if they can be justified.[8] According to James Turner Johnson, there is no normative tradition of pacifism in Islam.[9] Prior to the Hijra travel Muhammad struggled non-violently against his opposition in Mecca.[10] It was not until after the exile that the Quranic revelations began to adopt a more offensive perspective.[11] Fighting in self-defense is not only legitimate but considered obligatory upon Muslims, according to the Qur'an. The Qur'an, however, says that should the enemy's hostile behavior cease, then the reason for engaging the enemy also lapses.[12] History  Prior to the Hijra travel, Muhammad struggled non-violently against his opposition in Mecca,[10] providing a basis for Islamic pacifist schools of thought such as some Sufi orders and the Ahmadiyya movement.[14] Warfare in defense of the faith has also been part of Muslim history since the time of Muhammad,[9] with violence mentioned in Quranic revelations after their exile from Mecca.[15] In the 13th century, Salim Suwari, a philosopher in Islam, came up with a peaceful approach to Islam known as the Suwarian tradition.[1][2] The Senegalese sufi sheykh Amadou Bamba (1850–1927) spearheaded a non-violent resistance movement against French colonialism in West Africa. Amadou Bamba repeatedly rejected calls for jihad against the Europeans, preaching hard work, piety and education as the best means to resist the oppression and exploitation of his people. The earliest massive non-violent implementation of civil disobedience was brought about by Egyptians against British occupation in the Egyptian Revolution of 1919.[16] Zaghloul Pasha, considered the mastermind behind this massive civil disobedience, was a native middle-class, Azhar graduate, political activist, judge, parliamentary and ex-Cabinet Minister whose leadership brought Muslim and Christian communities together as well as women into the massive protests. Along with his companions of Wafd Party, who started campaigning in 1914, they have achieved independence of Egypt and a first constitution in 1923. According to Margaret Chatterjee, Mahatma Gandhi was influenced by Sufi Islam. She states that Gandhi was acquainted with the Sufi Chishti Order, whose Khanqah gatherings he attended, and was influenced by Sufi values such as humility, selfless devotion, identification with the poor, belief in human brotherhood, the oneness of God, and the concept of Fana.[17] David Hardiman notes that Gandhi's garb was similar that of Sufi pirs and fakirs, which was also noted by Winston Churchill when he compared Gandhi to a fakir.[18] According to Amitabh Pal, Gandhi followed a strand of Hinduism that bore similarities to Sufi Islam.[19] During the Indian independence movement, several Muslim organizations played a key role in nonviolent resistance against British colonial rule, including Khān Abdul Ghaffār Khān and his followers, as well as the All-India Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Khān Abdul Ghaffār Khān (6 February 1890 – 20 January 1988) (Pashto: خان عبدالغفار خان), nicknamed Bāchā Khān (Pashto: باچا خان, lit. "king of chiefs") or Pāchā Khān (پاچا خان), was a Pashtun independence activist against the rule of the British Raj. He was a political and spiritual leader known for his nonviolent opposition, and a lifelong pacifist and devout Muslim.[20] A close friend of Mohandas Gandhi, Bacha Khan was nicknamed the "Frontier Gandhi" in British India.[21] Bacha Khan founded the Khudai Khidmatgar ("Servants of God") movement in 1929, whose success triggered a harsh crackdown by the colonial authorities against him and his supporters, and they experienced some of the most severe repression of all Indian independence activists.[22] Khan strongly opposed the All-India Muslim League's demand for the partition of India.[23][24] When the Indian National Congress declared its acceptance of the partition plan without consulting the Khudai Khidmatgar leaders, he felt very sad and told the Congress "you have thrown us to the wolves."[25] After partition, Badshah Khan pledged allegiance to Pakistan and demanded an autonomous "Pashtunistan" administrative unit within the country, but he was frequently arrested by the Pakistani government between 1948 and 1954. In 1956, he was again arrested for his opposition to the One Unit program, under which the government announced to merge the former provinces of West Punjab, Sindh, North-West Frontier Province, Chief Commissioner's Province of Balochistan, and Baluchistan States Union into one single polity of West Pakistan. Badshah Khan also spent much of the 1960s and 1970s either in jail or in exile. Upon his death in 1988 in Peshawar under house arrest, following his will, he was buried at his house in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. Tens of thousands of mourners attended his funeral, marching through the Khyber Pass from Peshawar to Jalalabad, although it was marred by two bomb explosions killing 15 people. Despite the heavy fighting at the time, both sides of the Soviet–Afghan War, the communist army and the mujahideen, declared a ceasefire to allow his burial.[26] The Palestinian activist Nafez Assaily has been notable for his bookmobile service in Hebron dubbed "Library on Wheels for Nonviolence and Peace",[27] and hailed as a "creative Muslim exponent of non-violent activism".[28] The First Intifada began in 1987 initially as a nonviolent civil disobedience movement.[29][30] It consisted of general strikes, boycotts of Israeli Civil Administration institutions in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, an economic boycott consisting of refusal to work in Israeli settlements on Israeli products, refusal to pay taxes, refusal to drive Palestinian cars with Israeli licenses, graffiti, and barricading.[31][32] Pearlman attributes the non-violent character of the uprising to the movement's internal organization and its capillary outreach to neighborhood committees that ensured that lethal revenge would not be the response even in the face of Israeli state repression.[33] See also

References

Further reading

|