|

P3P

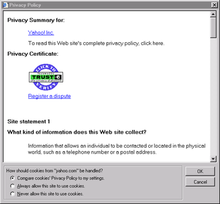

The Platform for Privacy Preferences Project (P3P) is an obsolete protocol allowing websites to declare their intended use of information they collect about web browser users. Designed to give users more control of their personal information when browsing, P3P was developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and officially recommended on April 16, 2002. Development ceased shortly thereafter and there have been very few implementations of P3P. Internet Explorer and Microsoft Edge Legacy were the only major browsers to support P3P. Microsoft has ended support from Windows 10 onwards. Internet Explorer and Edge [Legacy] on Windows 10 no longer support P3P as of 2016.[3] W3C officially obsoleted P3P on 2018-08-30.[4] The president of TRUSTe has stated that P3P has not been implemented widely due to the difficulty and lack of value.[5] PurposeAs the World Wide Web became a genuine medium in which to sell products and services, electronic commerce websites tried to collect more information about the people who purchased their merchandise. Some companies used controversial practices such as tracker cookies to ascertain the users' demographic information and buying habits, using this information to provide specifically targeted advertisements. Users who saw this as an invasion of privacy would sometimes turn off HTTP cookies or use proxy servers to keep their personal information secure. P3P was designed to give users a more precise control of the kind of information that they allow to release. According to the W3C, the main goal of P3P "is to increase user trust and confidence in the Web through technical empowerment".[6] P3P is a machine-readable language that helps to express a website’s data management practices. P3P manages information through privacy policies. When a website used P3P, they set up a set of policies that allows them to state their intended uses of personal information that may be gathered from their site visitors. When a user decided to use P3P, they set their own set of policies and state what personal information they will allow to be seen by the sites that they visit. Then when a user visited a site, P3P will compare what personal information the user is willing to release, and what information the server wants to get – if the two do not match, P3P would inform the user and ask if he/she is willing to proceed to the site, and risk giving up more personal information.[7] As an example, a user may store in the browser preferences that information about their browsing habits should not be collected. If the policy of a Website stated that a cookie is used for this purpose, the browser would automatically reject the cookie. The main content of a privacy policy is the following:

The privacy policy can be retrieved as an XML file or can be included, in compact form, in the HTTP header. The location of the XML policy file that applies to a given document can be:

P3P allows to specify a <META xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2002/01/P3Pv1">

<POLICY-REFERENCES>

<EXPIRY max-age="10000000"/><!-- about four months -->

</POLICY-REFERENCES>

</META>

User agent support Microsoft's Internet Explorer and Edge [Legacy] were the only mainstream web browsers that supported P3P.[8] Other browsers did not implemented it due to a perceived lack of value. IE provides the ability to display P3P privacy policies, and compare the P3P policy with the browser's settings to decide whether or not to allow cookies from a particular site. However, the P3P functionality in Internet Explorer extends only to cookie blocking, and will not alert the user to an entire web site that violates active privacy preferences. Microsoft considers the feature deprecated in its browsers and totally removed P3P support on Windows 10.[8] Mozilla supported some P3P features for a few years, but all P3P related source code was removed by 2007.[9] The Privacy Finder[10] service was also created by Carnegie Mellon's Usable Privacy and Security Laboratory. It is a publicly available "P3P-enabled search engine." A user can enter a search term along with their stated privacy preferences, and is then presented with a list of search results which are ordered based on whether the sites comply with their preferences. This works by crawling the web and maintaining a P3P cache for every site that ever appears in a search query. The cache is updated every 24 hours so that every policy is guaranteed to be relatively up to date. The service also allows users to quickly determine why a site does not comply with their preferences, as well as allowing them to view a dynamically generated natural language privacy policy based on the P3P data. This is advantageous over simply reading the original natural language privacy policy on a web site because many privacy policies are written in legalese and are extremely convoluted. Additionally, in this case the user does not have to visit the web site to read its privacy policy. BenefitsP3P allows browsers to understand their privacy policies in a simplified and organized manner rather than searching throughout the entire website. By setting privacy settings on a certain level, the user enables P3P to automatically block any cookies that the user might not want on their computer. Additionally, the W3C explains that P3P will allow browsers to transfer user data to services, ultimately promoting an online sharing community. Additionally, the P3P Toolbox[11] developed by the Internet Education Foundation recommends that anyone who is concerned about increasing their users’ trust and privacy should consider implementing P3P. The P3P toolbox site explains how companies have taken individuals data in order to promote new products or services. Furthermore, in recent years companies have taken individuals information and created profiles, which they then market without the individual's consent. Moreover, all this data is misused and we as consumers pay the price and become worrisome of issues such as: junk mail, identity theft and forms of discrimination; therefore implementing P3P's protocol is good and beneficial for web browsers. Moreover, since there has been an increase of browsers there are more users at risk running into privacy problems. But the Internet Education Foundation points out that, “P3P has been developed to help steer the force of technology a step further toward automatic communication of data management practices and individual privacy preferences.”[11] CriticismsThe Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) has been critical of P3P and believes P3P makes it too difficult for users to protect their privacy.[12] In 2002 it assessed P3P and referred to the technology as a "Pretty Poor Policy".[12] According to EPIC, some P3P software is too complex and difficult for the average person to understand, and many Internet users are unfamiliar with how to use the default P3P software on their computers or how to install additional P3P software. Another concern is that websites are not obligated to use P3P, and neither are Internet users. Moreover, the EPIC website claims that P3Ps protocol would become burdensome for the browser and not as beneficial or efficient as it was intended to be. A key problem that occurs with the use of P3P is that there is a lack of enforcement. Thus, promises made to users of P3P can go unfulfilled. Though by using P3P a company/website makes a promise of privacy and of the use of gathered data to the site’s users, there are no real legal ramifications if the company decides to use the information for other functions. Currently, there are no actual laws that have been passed by the United States about data protection. Though, ideally, companies should be honest as to their use of customers' personal information, there is no binding reason that the company must actually adhere to the rules it says it will comply by. Though using P3P technically qualifies as a contract, the lack of federal regulation downplays the need for companies to abide.[13] The agreement to use P3P not only puts in place unenforceable promises, but it also prolongs the adoption of federal laws that would actually inhibit the access and ability to use private information. If the government were to step in and attempt to protect Internet users with federal laws on what information can be accessed, and specific regulations on how user information can be used, companies would not maintain the leeway they do now to use information as they please, despite what they may actually tell users. In 2002, then EPIC employee Chris Hoofnagle argued that P3P was displacing chances for government regulation of privacy.[14] Critics of P3P also argue that non-compliant sites are excluded. According to a study done by CyLab Privacy Interest Group at Carnegie Mellon University[15] only 15% of the top 5,000 websites incorporate P3P. Therefore, many sites that do not include the code but do practice high privacy standards will not be accessible to users who use P3P as their only online privacy guide. EPIC also talks about how the development and implementation of P3P can cause a monopoly of private information. Since it tends to be only major companies who implement P3P on their websites, only these major companies are tending to then gather this information seeing as only their privacy policies can compare to privacy preferences of users. The EPIC website says, "The incredible complexity of P3P, combined with the way that popular browsers are likely to implement the protocol would seem to preclude it as a privacy-protective technology," EPIC continues on to state, "Rather, P3P may actually strengthen the monopoly position over personal information that U.S. data marketers now enjoy."[12] The failure for its immediate adoption can be related to the idea of it being a notice and choice approach that does not comply with the Fair Information Practices. According to the Chairman of the FTC,[16] privacy laws are key in today’s society in order to protect the consumer from providing too much personal information for others’ benefit. Some believe that there should be a limit to the collection and use of the consumer’s personal data online. Currently, sites are not required under any United States laws to comply with the privacy policies they publish, therefore P3P causes some controversy with consumers who are concerned about the release of their personal information and are only able to rely on P3P’s protocol to protect their privacy. Michael Kaply from IBM is reported saying the following when the Mozilla Foundation was considering the removal of P3P support from their browser-line in 2004:[17]

Live Leer, a PR manager for Opera Software, explained in 2001 the deliberate lack of P3P support in their browser:[18]

AlternativesP3P user agents are not the only option available for Internet users that want to ensure their privacy. Several of the main alternatives to P3P include using web browsers' privacy mode, anonymous e-mailers and anonymous proxy servers. The main alternative to P3P may not be these technologies, but instead stronger laws to regulate what kind of information from Internet users can be collected and retained by websites. For example, in Europe, the General Data Protection Regulation provides individuals with a certain set of principles about how personal information is collected and the person's rights to protecting their personal data.[19] The act allows individuals to control the type of information that is being collected from them. Various principles are included within the act, such as the rule that individual has the right to retrieve the data collected about them at any time under certain conditions. Moreover, the individual's personal information cannot be kept longer than necessary, and not be used for purposes other than those agreed upon to begin with. Currently, the United States has no federal law protecting the privacy of personal information shared online. However, there are some sectoral laws at the federal and state level that offer some protection for certain types of information collected about individuals.[20] For example, the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) of 1970 makes it legal for consumer reporting agencies to disclose personal information only under three specified circumstances: credit, employment or insurance evaluation; government grant or license; or a “legitimate business need” that involves the consumer. A list of other sectoral privacy laws in the United States can be viewed at the Consumer Privacy Guide's website.[20] See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||