|

Maluku Islands

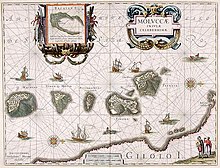

The Maluku Islands (/məˈluːkuː, mæˈluːkuː/ mə-LOO-koo, mal-OO-; Indonesian: Kepulauan Maluku) or the Moluccas (/məˈlʌkəz/ mə-LUK-əz) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located east of Sulawesi, west of New Guinea, and north and east of Timor. Lying within Wallacea (mostly east of the biogeographical Weber Line), the Moluccas have been considered a geographical and cultural intersection of Asia and Oceania. The islands were known as the Spice Islands because of the nutmeg, mace, and cloves that were exclusively found there, the presence of which sparked European colonial interests in the 16th century.[3] The Maluku Islands formed a single province from Indonesian independence until 1999, when they were split into two provinces. A new province, North Maluku, incorporates the area between Morotai and Sula, with the arc of islands from Buru and Seram to Wetar remaining within the existing Maluku Province. North Maluku is predominantly Muslim, and its capital is Sofifi on Halmahera island. Maluku province has a larger Christian population, and its capital is Ambon. Though originally Melanesian,[4] many island populations especially in the Banda Islands, were massacred in the 17th century during the Dutch–Portuguese War, also known as the Spice War. A second influx of immigrants primarily from Java began in the early 20th century under the Dutch and continues in the Indonesian era, which has also caused a lot of controversy as the Transmigrant programs are thought to be a contributing factor to the Maluku Riots.[5] EtymologyThe etymology of the word Maluku is unclear and has been a matter of debate for many experts.[6] The first recorded word that can be identified with Maluku comes from Nagarakertagama, an Old Javanese eulogy of 1365. Canto 14 stanza 5 mentioned Maloko, which Pigeaud identified with Ternate or Moluccas.[7]: 17 [8]: 34 A theory holds that Maluku comes from the phrase Moloko Kie Raha or Moloku Kie Raha. In the Ternate language, raha means "four", while kie here means "mountain". Kie raha or "four mountains" refers to Ternate, Tidore, Bacan, and Jailolo (the name Jailolo has been used in the past to refer to Halmahera island), all of which have their kolano (a local title for kings rooted in Panji tales).[9] It is unclear what the meaning of Moloko or Moloku is. One possible meaning is in Ternate language, it meant "to hold or grasp", in which case Moloko Kie Raha could be understood to mean "Confederation of the Four Mountains". Another possibility is that the word originates from the word maloko, which is a combination of the particle ma- and the root loko in North Halmahera languages means the variety of words relating to the location of mountains, in which case "Maloko Kie Raha" in the phrase "Ternate se Tidore, Moti se Mara Maloko Kie Raha" means "Ternate, Tidore, Moti, and Mara the place of the four mountains" or with the shifting of pronunciation of loko towards luku, means "Ternate, Tidore, Moti, and Mara the world of the four mountains".[10] History Early historyAustralo-Melanesians were the first people to inhabit the islands at least 40,000 years ago, and then a later migration of Austronesian speakers around 2000 BC.[11] Other archaeological finds showed possible Arab merchants began to arrive in the fourteenth century, bringing Islam. The conversion to Islam occurred in many islands,[citation needed] especially in the centres of trade, while aboriginal animism persisted in the hinterlands and more isolated islands. Archaeological evidence here relies largely on the occurrence of pigs' teeth, as evidence of pork eating or abstinence therefrom.[12] Remnants of Majapahit expeditions were also found in oral as well as archaeological sites. A story from Letvuan on Kai Kecil island, tells of a Balinese envoy of Gajah Mada by the name of Kasdev, his wife Dit Ratngil, and eight of their children. Archaeological sites of ancient tombs found in Sorbay Bay south of Letvuan seemed to support the story as well as some cultural practices of Kei of Balinese origin.[13] Other archaeological finds in Kei islands include Shiva statue from Kei Besar island. Another oral story was of 14th century Majapahit expedition to Negeri Ema, Ambon Island, by an envoy named Nyi Mas Kenang Eko Sutarmi alongside 22 of her retinues, and a spear bearer trying to form an alliance and trading relationship with Negeri Ema's leader by the name of Kapitan Ading Adang Anaan Tanahatuila. The meeting was facilitated by Malessy Soa Lisa Maitimu; however, it failed to reach an agreement. As Sutarmi failed, she decided to stay in exile while her retinues settled and married locals of Ema, and her spear bearer settled on the coast but was killed later by Gunung Maut troops. Archaeological finds relating to this expedition include a water source with Sun symbols with nine rays, and heirlooms of spears and Totobuang kept by the Maitimu family and village office of Negeri Ema, alongside many potteries.[14] Portuguese  In August 1511 the Portuguese conquered the city-state of Malacca. The most significant lasting effects of the Portuguese presence were the disruption and reorganization of the Southeast Asian trade, and in eastern Indonesia—including Maluku—the introduction of Christianity.[15] One Portuguese diary noted, "It is over thirty years since they became Moors".[16] Afonso de Albuquerque learned of the route to the Banda Islands and other 'Spice Islands', and sent an exploratory expedition of three vessels under the command of António de Abreu, Simão Afonso Bisigudo, and Francisco Serrão.[17] On the return trip, Serrão was shipwrecked at Hitu island (northern Ambon) in 1512. There he established ties with the local ruler who was impressed with his martial skills. The rulers of the competing island states of Ternate and Tidore also sought Portuguese assistance and the newcomers were welcomed in the area as buyers of supplies and spices during a lull in the regional trade due to the temporary disruption of Javanese and Malay sailings to the area following the 1511 conflict in Malacca. The spice trade soon revived but the Portuguese would not be able to fully monopolize or disrupt this trade.[18] Allying himself with Ternate's ruler, Serrão constructed a fortress on that tiny island and served as the head of a mercenary band of Portuguese seamen under the service of one of the two local feuding sultans who controlled most of the spice trade. Both Serrão and Ferdinand Magellan, however, perished before they could meet one another.[18] The Portuguese first landed in Ambon in 1513, but it only became the new centre for their activities in Maluku following the expulsion from Ternate. European power in the region was weak and Ternate became an expanding, fiercely Islamic, and anti-European state; the Portuguese-Ternate wars raged throughout the reigns of Sultan Baab Ullah (r. 1570–1583) and his son Sultan Saidi Berkat (r. 1583–1606).[19] Following Portuguese missionary work, there have been large Christian communities in eastern Indonesia through to contemporary times, which has contributed to a sense of shared interest with Europeans, particularly among the Ambonese.[19]  DutchThe Dutch arrived in 1599 and competed with the Portuguese in the area for trade.[20] The Dutch East India Company in the course of Dutch–Portuguese War allied with the Sultan of Ternate and conquered Ambon and Tidore in 1605, expelling the Portuguese. A Spanish counterattack from the Philippines restored Iberian rule in parts of North Maluku up to 1663. However, the Dutch monopolized the production and trade of spices through a ruthless policy. This included the genocidal conquest of the nutmeg-producing Banda Islands in 1621, the elimination of the English in Ambon in 1623, and the subordination of Ternate and Tidore in the 1650s. An anticolonial resistance movement led by a Tidore prince, the Nuku Rebellion, engulfed large parts of Maluku and Papua in 1780-1810 and co-opted the British. During the French Revolutionary Wars and again in the Napoleonic Wars, British forces captured the islands in 1796–1801 and 1810, respectively, and held them until 1817. In that time they uprooted many of the spice trees for transplantation throughout the British Empire.[21]  After Indonesian independenceWith the declaration of a single republic of Indonesia in 1950 to replace the federal state, a Republic of South Maluku (Republik Maluku Selatan, RMS) was declared and attempted to secede,[citation needed] led by Chris Soumokil (former Supreme Prosecutor of the Eastern Indonesia state) and supported by the Moluccan members of the Netherlands KNIL special troops. This movement was defeated by the Indonesian army and by special agreement with the Netherlands the Moluccan troops were ordered to move to the Netherlands.[citation needed]. Decades later, descendants of these Moluccan KNIL soldiers participated in the 1975 Dutch train hostage crisis, the 1977 Dutch train hijacking, and the 1977 Dutch school hostage crisis to bring attention to their plight for an independent Republic of South Maluku. Maluku is one of the first provinces of Indonesia, proclaimed in 1945 and lasting until 1999 when the Maluku Utara and Halmahera Tengah Regencies were split off as a separate province of North Maluku. Its capital used to be Ternate, on a small island to the west of the large island of Halmahera, but has been moved to Sofifi on Halmahera itself. The capital of the remaining part of Maluku province remains at Ambon.[citation needed] 1999–2003 inter-communal conflictReligious and ethnic conflict erupted across the islands in January 1999. The subsequent 18 months were characterized by fighting between local groups of Muslims and Christians against jihadist groups from Java and the Indonesian military backing them leading to the destruction of thousands of houses, the displacement of approximately 500,000 people, the loss of thousands of lives, and the segregation of Muslims and Christians.[22] GeographyThe Maluku Islands have a total area of 850,000 km2 (330,000 sq mi), 90% of which is sea.[23] There are an estimated 1027 islands.[24] The largest two islands, Halmahera and Seram, are sparsely populated, while the most developed, Ambon and Ternate, are small.[24] The majority of the islands are forested and mountainous. The Tanimbar Islands are dry and hilly, while the Aru Islands are flat and swampy. Mount Binaiya (3,027 m; 9,931 ft) on Seram is the highest mountain. Several islands, such as Ternate (1,721 m; 5,646 ft) and the TNS islands, are volcanoes emerging from the sea with villages sited around their coasts. There have been over 70 serious volcanic eruptions in the last 500 years and earthquakes are common.[24]

GeologyThe geology of the Maluku Islands shares much similar history, characteristics, and processes with the neighbouring Nusa Tenggara region. There is a long history of geological study of these regions since Indonesian colonial times; however, the geological formation and progression are not fully understood, and theories of the island's geological evolution have changed extensively in recent decades.[25] The Maluku Islands comprise some of the most geologically complex and active regions in the world,[26] resulting from their position at the meeting point of four geological plates and two continental blocks. Ecology Biogeographically, all of the islands apart from the Aru group lie in Wallacea, the region between the Sunda Shelf (part of the Asia block), and the Arafura Shelf (part of the Australian block). More specifically, they lie between Weber's Line and Lydekker's Line and thus have a fauna that is rather more Australasian than Asian. Malukan biodiversity and its distribution are affected by various tectonic activities; most of the islands are geologically young, being from 1 million to 15 million years old, and have never been attached to the larger landmasses. The Maluku islands differ from other areas in Indonesia; they contain some of the country's smallest islands, coral island reefs scattered through some of the deepest seas in the world, and no large islands such as Java or Sumatra. Flora and fauna immigration between islands is thus restricted, leading to a high rate of endemic biota evolving.[25] The ecology of the Maluku Islands has fascinated naturalists for centuries; Alfred Wallace's book, The Malay Archipelago, was the first significant study of the area's natural history and remains an important resource for studying Indonesian biodiversity. Maluku is the subject of two major historical works of natural history by Georg Eberhard Rumphius: the Herbarium Amboinense and the Amboinsche Rariteitkamer.[27] Rainforest covered most of northern and central Maluku, which, on the smaller islands has been replaced by plantations, including the region's endemic cloves and nutmeg. The Tanimbar Islands and other southeastern islands are arid and sparsely vegetated, much like nearby Timor.[24] In 1997 the Manusela National Park, and in 2004, the Aketajawe-Lolobata National Park, were established, for the protection of endangered species.[citation needed] Nocturnal marsupials, such as cuscus and bandicoots, make up the majority of the mammal species and introduced mammals include Malayan civets and feral pigs.[24] Bird species include approximately 100 endemics with the greatest variety on the large islands of Halmahera and Seram. North Maluku has two species of endemic birds of paradise.[24] Uniquely among the Maluku Islands, the Aru Islands have a purely Papuan fauna including kangaroos, cassowaries, and birds of paradise.[24] While many ecological problems affect both small islands and large landmasses, small islands suffer their particular problems. Development pressures on small islands are increasing, although their effects are not always anticipated. Although Indonesia is richly endowed with natural resources, the resources of the small islands of Maluku are limited and specialised; furthermore, human resources, in particular, are limited.[28] General observations[29][30] about small islands that can be applied to the Maluku Islands include:[28]

ClimateCentral and southern Maluku Islands experience the dry monsoon between October and March and the wet monsoon from May to August, which is the reverse of the rest of Indonesia. The dry monsoon's average maximum temperature is 30 °C (86 °F) while the wet's average maximum is 23 °C (73 °F). Northern Maluku has its wet monsoon from December to March in line with the rest of Indonesia. Each island group has its climatic variations, and the larger islands tend to have drier coastal lowlands and their mountainous hinterlands are wetter.[24] Demographics ReligionReligion in Maluku Islands (December 2023)[31] Islam (61.87%) Protestantism (33.40%) Roman Catholic (4.23%) Folk religion (0.26%) Hinduism (0.23%) Buddhism (0.02%) Confucianism (0.005%)

PopulationThe population of Maluku Province in 2020 was 1,848,923 and that of North Maluku Province was 1,282,937.[2] Hence the total population of the Maluku Islands as a region in 2020 was 3,131,860. Ethnic groupsA long history of trade and seafaring has resulted in a high degree of mixed ancestry in Malukans.[24] Austronesian peoples added to the native Melanesian population around 2000 BCE.[32] Melanesian features are strongest in the islands of Kei and Aru and amongst the interior people of the islands Seram and Buru. Later added to this Austronesian-Melanesian mix were some Indian and Arab strain. More recent arrivals include Bugis trader settlers from Sulawesi and Javanese transmigrants.[24] LanguagesOver 130 languages were once spoken across the islands; however, many have now switched to the creoles of Ternate and Ambonese, the lingua franca of northern and southern Maluku, respectively.[24] Government and politicsAdministrative divisionsThe Maluku Islands are divided into two provinces: Maluku and North Maluku. EconomyCloves and nutmeg are still cultivated, as are cocoa, coffee and fruit. Fishing is a big industry across the islands but particularly around Halmahera and Bacan. The Aru Islands produce pearls, and Seram exports lobsters. Logging is a significant industry on the larger islands with Seram producing ironwood and teak and ebony are produced on Buru.[24] See also

ReferencesCitations

General and cited references

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Moluccas. Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Maluku Islands.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||