|

Juan Granell Pascual

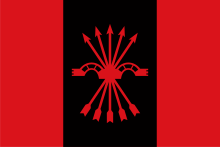

Juan Granell Pascual (1902-1962) was a Spanish politician, official and businessman. Politically he first supported the Carlist cause and served in the Republican Cortes in 1933–1936. After the Civil War he turned into a militant and zealous Francoist. His political career climaxed in the early 1940s; in 1939-1945 he was member of the FET executive Consejo Nacional, in 1940-1941 he was the civil governor and the provincial FET leader in Biscay, in 1940-1941 he served in Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo, in 1941-1945 he was sub-secretary of industry in the Ministry of Industry and Commerce and member of the Instituto Nacional de Industria council. In 1943-1949 during two terms he was member of Cortes Españolas. In 1945-1953 he managed the state-run energy conglomerate ENDESA and was responsible for construction of the first coal-fired thermal power plant in Spain; he was also in executive bodies of numerous other companies. Family and youth The Granell family is of Catalan origin; in the region of Valencia it was first noted in the mid-13th century and in the area of Castellón in the late 14th century.[1] In the course of the centuries it got very branched and popular along all the Spanish Mediterranean coast and numerous individuals rose to publicly recognizable figures, but none of them has been identified as related to Granell Pascual.[2] His family branch originated from Bétera near Valencia[3] but in the early 18th century they settled in the port town of Burriana, south of Castellón.[4] From then on 4 successive generations lived in Burriana, including Juan's grandfather, Juan Bautista Granell Fandos.[5] His social status is unclear and none of the sources consulted provides information what he was doing for a living, though some suggest that the family owned a large "finca citrícola" on the right bank of the Mijares river and were growing lemons and oranges.[6] Granell Fandos’ son, Vicente Granell Blanch (1869-after 1940[7]), in 1892 married a girl from another family of local orange growers,[8] Dolores Pascual Mingarro.[9] The couple settled in Burriana and had at least 3 children, born in 1893–1902; Juan was the youngest one. As a boy Juan first frequented a private school in Burriana.[10] In his early teens he became a boarder in the Jesuit Colegio de San José in Valencia,[11] where he was noted between 1915 and 1918.[12] At unspecified time though probably in the late 1910s he moved to Madrid to commence higher education and enrolled at Escuela de Mecánica y Electricidad, a Jesuit technical school currently known as Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería.[13] It is not clear when he graduated as engineer; in 1928 he was referred to as “ingeniero electricista”.[14] It is neither known what he was doing for a living in the late 1920s; one scholar when discussing his career in the early 1930s describes Granell Pascual as “a successful engineer”,[15] but provides no details on his professional career. Also press of the early 1930s consistently referred to him, as “ingeniero”,[16] “ingeniero industrial”[17] or “ingeniero mecánico electricista”.[18]  In 1933[19] Granell married Aurelia Concepción Vicent Planes (1905-1999), a girl from the local bourgeoisie family also engaged in the orange business.[20] It is not clear whether the couple settled in Burriana[21] or in Madrid.[22] They had 6 children, born between the mid-1930s and the late 1940s: Juan María, María Begoña, Vicente, Jesús, Ignacio and Javier Granell Vicent.[23] None of them became a nationwide known figure, though some were recognized locally. Juan María,[24] Jesús[25] and Ignacio[26] worked as civil engineers, mostly in construction business; some held also teaching positions,[27] while Javier became the head surgeon in the public Madrid health service.[28] Currently the engineering tradition is cultivated by the third generation, as Granell Pascual's grandson Carlos Granell Ninot works in construction business and is the secretary of SPANCOLD, the engineering association focused on dams and hydrotechnical works.[29] Early political engagements None of the sources consulted provides information on political preferences of Granell's ancestors; in Burriana many Granells tended to sympathize with the conservatives.[30] Some data suggest that his father might have been related to Integrism[31] and that he remained a militant Catholic;[32] later propaganda prints claimed that Granell Pascual inherited the Traditionalist outlook, possibly highly flavored with Carlism, from his forefathers.[33] There is no information on his political engagements prior to late 1931, when Granell Pascual was listed among the Madrid Integrists who paid homage to the defunct Carlist king, Don Jaime.[34] He then joined the united Carlist organisation Comunión Tradicionalista and since early 1932 he was noted speaking at Carlist meetings in Burriana, accompanied by former Integrists like Manuel Senante.[35] In early 1933 latest he entered the provincial party executive, Junta Provincial,[36] and later during the year he used to speak at local rallies.[37] During the 1933 electoral campaign to the Cortes the Castellón Carlists, led by Jaime Chicharro and Juan Bautista Soler, closed an alliance agreement with other right-wing organisations; Granell was included on the joint provincial list of candidates of Unión de Derechas. He campaigned focused on religious issues and protested alleged anti-Catholic governmental policy;[38] following some controversies related to a rival lerrouxista counter-candidate eventually Comisión de Actas declared him elected.[39] In the parliament he joined the Carlist minority[40] but remained on the back benches and some authors claim he went unnoticed in the chamber.[41] Following the October 1934 unrest he formed part of a commission which investigated the events in Barcelona[42] and in 1935 he co-signed a joint motion in Cortes[43] to prosecute Manuel Azaña.[44] Granell did not feature prominently in the national Carlist organization; his only central role identified is membership in Tesoro de la Tradición, a financial branch of the executive.[45] He kept serving in the Castellón Junta Provincial; it was led by Juan Bautista Soler,[46] though some authors claim that Granell led the junta himself.[47] He remained engaged in regular local activities, like opening new círculos[48] or speaking at rallies, e.g. in Castellón[49] during so-called Gran Semana Tradicionalista,[50] in Onteniente[51] or Benicarló.[52] His particular focus was on confronting masonry.[53] The party propaganda presented him as a representative of “la nueva generación de tradicionalistas” and a “disciplined soldier” of the cause.[54]  Since 1936 there is scarcely any information on Granell during the following 4 years. Neither contemporary press nor historiography mention him as a candidate standing in the Cortes elections of 1936. It is not clear whether he was engaged in anti-Republican conspiracy and none of the sources consulted provides information on his fate during the Civil War. Some authors claim that he "supported the rebel faction", but provide neither details nor references.[55] Unlike in case of former combatants, none of numerous hagiographic press notes published during his later career in Francoist ranks refers to his wartime deeds. One literary work suggests that Granell and his family spent the war in hiding in Grao de Burriana[56] and emerged in public in July 1938.[57] Political climax (1939-1945) In early August 1939 Granell was nominated Delegado de Prensa y Propaganda in Valencia,[58] head of the regional Falange Española Tradicionalista press and media service;[59] in this role he also used to publish some militant Francoist propaganda articles in local press.[60] In September 1939 and as one of 13 tractable Carlists[61] he was nominated to the second Consejo Nacional of Falange,[62] and in March 1940 he was appointed as member to the newly established Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo. Exact mechanism of his elevation is unclear; some authors speculate that it might have been related to the Jesuit influence, his own anti-masonic zeal and connections to pro-Franco collaborative faction within Carlism.[63] In October 1940 Granell assumed the post of civil governor of the province of Biscay.[64] As civil governor Granell abandoned any Carlist sentiments he might have still nurtured and adopted a vehement, militant Falangist stand, pursued in terms of propaganda arrangements and personal appointments.[65] He found himself at odds with the Bilbao mayor and provincial Biscay FET leader, another Carlist José María Oriol, who attempted to cultivate moderate Traditionalist policy.[66] Following a series of clashes[67] Oriol resigned as FET jefe provincial in December 1940 and was replaced by Granell himself.[68] In February 1941 Oriol left also the position of Bilbao alcalde, and Granell emerged unchallenged as the key regime personality in the province. According to later homage article his focus was mostly on industry and social questions,[69] though he took part also in routine propaganda endeavors.[70] In April 1941 he ceased as member of the anti-masonic Tribunal.[71] In July 1941 Granell was released as civil governor and moved to central administration; he assumed the post of Subsecretario de industria in the Ministry of Industry and Commerce.[72]  As industry sub-secretary Granell identified 5 priorities: irrigation, electrification, coal production, fuel industry and transport.[73] He entered the council of INI[74] and worked closely with Suanzes on development of state-controlled conglomerates, especially ENDESA, Empresa Nacional de Electricidad.[75] He contributed also to re-structuring of the Falangist syndicates.[76] The British intelligence considered him so prominent a figure that they produced rumors about Granell.[77] In 1942 he was re-appointed to the 3rd Consejo Nacional of FET[78] and as its member in 1943 he automatically became member of the newly established Cortes Españolas;[79] he entered Comisión de Industria y Comercio.[80] His career went into decline in 1945; he was released from the sub-secretary post[81] and was not re-appointed to the 4th Falangist Consejo. However, upon expiry of his Cortes ticket he got it renewed from the pool of personal Franco's appointees. He briefly approached the minoritarian Carlist carloctavista faction and entered Consejo Permanente of the pretender Carlos VIII,[82] but was not among its protagonists.[83] The mainstream Javierista faction declared him a traitor and while some Falangists were allowed re-entry into Comunión, Granell along 5 other individuals was specifically listed as not eligible.[84] Later careerHaving left the Ministry of Industry in 1945 Granell assumed management of one of the flagship INI companies, ENDESA.[85] In corporate historiography he is recorded as ingenious, dedicated and enthusiastic manager, who used to visit construction sites during weekends.[86] As most of Spanish electricity was produced by hydrotechnical installations, his focus was on diversification and development of thermal power plants. These efforts bore fruit in 1949,[87] with opening of the first Spanish coal-fired plant in Compostilla;[88] it was also the first power plant built by ENDESA.[89] However, over time Granell developed discrepancies with Suanzes over the question of ownership of electricity infrastructure; some authors claim he advocated a joint public-private partnership against the Suanzes-advanced state-run model,[90] others suggest that the two went together rather well and that Granell actually advocated expropriation of private energy concessions.[91] It is not clear whether these issues contributed to Granell not having his Cortes ticket renewed in 1949, the year which marked his final exit from politics. Eventually Granell resigned from ENDESA management in 1953, according to some due to differences with Suanzes.[92] Some authors claim that Granell “se retiró de la política para atender a sus negocios”,[93] but there is no evidence that he was running his own private business. Instead, he entered executive boards of numerous large companies. Some were partially controlled by INI, like the fuel giant Compañía Arrendataria del Monopolio del Petróleo CAMPSA, Empresa Nacional Hidroeléctrica del Ribagorzana ENHER[94] or Asbestos Españoles.[95] Some were strictly private enterprises, like the construction conglomerate Dragados y Construcciones, another construction firm Sociedad Boetticher y Navarro or the insurance company Unión Levantina.[96] Some were related to municipal authorities, like the credit company Casa de Valencia, which he presided since the late 1940s.[97] At least in some of these companies, like in Boetticher y Navarro, Granell performed high executive roles until the early 1960s.[98]  Since expiry of his Cortes ticket Granell remained politically inactive. However, he remained on excellent terms with the regime. In 1954 he was admitted at a private audience by Franco;[99] he spoke to caudillo in similar circumstances at least also in 1957,[100] 1958[101] and 1962.[102] He received Gran Cruz de Isabél la Católica, Gran Cruz del Mérito Civil[103] and Gran Cruz de la Orden de Cisneros.[104] Resident in Madrid,[105] he became the unofficial Burriana representative in the capital[106] and was credited for numerous local investments, be it the road and railway infrastructure development, water delivery and drainage system upgrades, refurbishment and enhancement of Guardia Civil offices, extension of piers and construction of new buildings in the harbor,[107] saving local college from closure[108] and especially reconstruction of the iconic El Salvador church bell-tower, blown up by retreating Republican troops.[109] Already in the 1940s he was declared hijo predilecto of Burriana;[110] after death[111] a large plaza was named after him,[112] to be renamed in the post-Francoist era. See alsoFootnotes

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||||