|

Great Bible

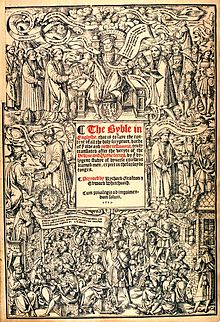

The Great Bible of 1539 was the first authorised edition of the Bible in English, authorised by King Henry VIII of England to be read aloud in the church services of the Church of England. The Great Bible was prepared by Myles Coverdale, working under commission of Thomas Cromwell, Secretary to Henry VIII and Vicar General. In 1538, Cromwell directed the clergy to provide "one book of the Bible of the largest volume in English, and the same set up in some convenient place within the said church that ye have care of, whereas your parishioners may most commodiously resort to the same and read it." The Great Bible includes much from the Tyndale Bible, with the objectionable features revised. As the Tyndale Bible was incomplete, Coverdale translated the remaining books of the Old Testament and Apocrypha from the Latin Vulgate and German translations, rather than working from the original Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic texts. Although called the Great Bible because of its large size, it is known by several other names as well: the King's Bible, because the King Henry VIII of England authorized and permitted it; the Cromwell Bible, since Thomas Cromwell directed its publication; Whitchurch's Bible after its first English printer; the Chained Bible, since it was chained to prevent removal from the church. It has less accurately been termed Cranmer's Bible, since although Thomas Cranmer was not responsible for the translation, a preface by him appeared in the second edition.[1] Sources and historyThe Tyndale New Testament had been published in 1525, followed by his English version of the Pentateuch in 1530; but both employed vocabulary, and appended notes, that were unacceptable to English churchmen, and to the King. Tyndale's books were banned by royal proclamation in 1530, and Henry then held out the promise of an officially authorised English Bible being prepared by learned and catholic scholars. In 1534, Thomas Cranmer sought to advance the King's project by press-ganging ten diocesan bishops to collaborate on an English New Testament, but most delivered their draft portions late, inadequately, or not at all. By 1537 Cranmer was saying that the proposed Bishops' Bible would not be completed until the day after Doomsday. The King was becoming impatient with the slow progress, especially in view of his conviction that the Pilgrimage of Grace had been substantially exacerbated due to the rebels' exploitation of popular religious ignorance. With the bishops showing no signs of completing their task, Cromwell obtained official approval for the Matthew Bible as an interim measure in 1537, the year of its publication under the pseudonym "Thomas Matthew", actually John Rogers.[2][3] Cromwell had helped to fund the printing of this version.[4] The Matthew Bible combined the New Testament of William Tyndale, and as much of the Old Testament as Tyndale had been able to translate before being put to death the prior year for heresy. Coverdale's translation of the Bible from the Latin into English and Matthew's translation of the Bible using much of Tyndale's work were each licensed for printing by Henry VIII, but neither was fully accepted by the Church. By 1538, it became compulsory for all churches to own a Bible in accordance with Cromwell's Injunctions to the Clergy.[5][6] Coverdale based the Great Bible on Tyndale's work, but removed the features objectionable to the bishops. He translated the remaining books of the Old Testament using mostly the Latin Vulgate and German translations.[7] Coverdale's failure to translate from the original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek texts gave impetus to the Bishops' Bible. The Great Bible's New Testament revision is chiefly distinguished from Tyndale's source version by the interpolation of numerous phrases and sentences found only in the Vulgate. For example, here is the Great Bible's version of Acts 23:24–25 (as given in The New Testament Octapla[8]):

The non-italicised portions are taken over from Tyndale without change, but the italicised words, which are not found in the Greek text translated by Tyndale, have been added from the Latin. (The added sentence can also be found, with minor verbal differences, in the Douai-Rheims New Testament.) These inclusions appear to have been done to make the Great Bible more palatable to conservative English churchmen, many of whom considered the Vulgate to be the only legitimate Bible. The psalms in the Book of Common Prayer of 1662 continue to be taken from the Great Bible rather than the King James Bible. In 1568, the Great Bible was superseded as the authorised version of the Anglican Church by the Bishops' Bible. The last of over 30 editions of the Great Bible appeared in 1569.[9] PrintingMyles Coverdale and Richard Grafton went over to Paris and put the work into the hands of the French printer, François Regnault at the University of Paris, with the countenance of Bonner, then (Bishop Elect of Hereford and) British Ambassador at Paris. There was constant fear of the Inquisition. Coverdale packed off a large quantity of the finished work through Bonner to Cromwell, and just when this was done, the officers of the Inquisition came on the scene. Coverdale and Grafton made their escape. A large quantity of the printed sheets were sold as waste paper to a haberdasher, who resold them to Cromwell's agents, and they were, in due course, sent over to London. Cromwell bought the type and presses from Regnault and secured the services of his compositors.[10] The first edition[11] was a run of 2,500 copies that were begun in Paris in 1539. Much of the printing – in fact 60 percent – was done at Paris, and after some misadventures where the printed sheets were seized by the French authorities on grounds of heresy (since relations between England and France were somewhat troubled at this time), the remaining 40 percent of the publication was completed in London in April 1539.[7] Two luxurious editions were printed to showcase for presentation. One edition was produced for King Henry VIII and the other for Thomas Cromwell. Each was printed on parchment rather than on paper. The woodcut illustrations of these editions, moreover, were then exquisitely painted by hand to look like illuminations. Today, the copy that was owned by King Henry VIII is held by the British Library in London, England. Thomas Cromwell's edition is today held by the Old Library at St John's College in Cambridge, England. It went through six subsequent revisions between 1540 and 1541. The second edition of 1540 included a preface by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, recommending the reading of the scriptures. (Cranmer's preface was also included in the front of the Bishops' Bible.) Seven editions of the Great Bible were published in quick succession.[12] 1. 1539, April – Printed in Paris and London by Richard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch. 8. 1549, ________ – Printed in London by Edward Whitchurch.[13] 9. "In 1568, the Great Bible was superseded as the authorised version of the Anglican Church by the Bishops' Bible. The last of over 30 editions of the Great Bible appeared in 1569."[14] A version of Cranmer's Great Bible can be found included in the English Hexapla, produced by Samuel Baxter and Sons in 1841. However copies of this work are fairly rare. The most available reprinting of the Great Bible's New Testament (minus its marginal notes) can be found in the second column of the New Testament Octapla edited by Luther Weigle, chairman of the translation committee that produced the Revised Standard Version.[15] LanguageThe language of the Great Bible marks the advent of Early Modern English. Moreover, this variant of English is pre-Elizabethan. The text, which was regularly read in the parish churches, helped to standardise and stabilise the language across England. Some of the readings of the First Authorised Version of the Bible differ from the more familiar 1611 edition, the Third Authorised Version. For example, the commandment against adultery in the Great Bible reads, "Thou shalt not breake wedlocke."[16] IllustrationsThe woodcut illustrations in the earlier editions of the Great Bible evidence a lack of projective geometry in their designs. Though this Bible falls into the Renaissance period of Bible production in the early years of the Protestant Reformation of church theology and religious practice, the artwork used in the Great Byble more closely resembles the woodcut illustrations found in a typical Biblia pauperum from the medieval period. The woodcut designs appear in the 1545 edition of Le Premier [-second] volume de la Bible en francoiz nouvellement hystoriee, reveue & corrigee oultre les precedentes impressions published in Paris by Guillaume Le Bret, and now held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Réserve des livres rares, A-282. "[17] The style employed by the French woodcutter appears to have been influenced by the Venetian engraver Giovanni Andrea Valvassori, who in 1511 produced the block print picture bible Opera nova contemplativa.[18] In 2020, it was discovered that the illustrations in Henry VIII's personal copy had been altered to appeal to the king.[19] AftermathThe later years of Henry VIII were marked by serious reaction. In 1542 Convocation with the royal consent made an attempt thwarted by Cranmer to Latinise the English version and to make it in reality what the Catholic version of Rheims subsequently became. In the following year Parliament (which then practically meant the King and two or three members of the Privy Council) restricted the use of the English Bible to certain social classes – excluding nine tenths of the population. Three years later it would prohibit the use of everything but the Great Bible. It was probably at this time that there took place the great destruction of all previous work on the English Bible which has rendered examples of that work so scarce. Even Tunstall and Heath were anxious to escape from their responsibility in lending their names to the Great Bible. In the midst of this reaction Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547.[20] See also

References

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Great Bible.

|

||||||||||||||||||||