|

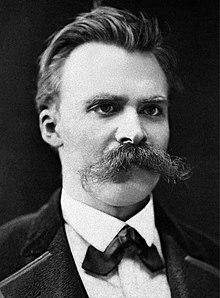

Friedrich Nietzsche's views on women

Friedrich Nietzsche's views on women have attracted controversy, beginning during his life and continuing to the present. Assessments by contemporariesIda von Miaskowski was the wife of the economist August von Miaskowski, who taught at the University of Basel. Between 1874 and 1876 Nietzsche had close relations with her family. In her memoir of Nietzsche, published seven years after his death, she remarked:

Despite Nietzsche's writings being viewed as being misogynistic by many, others, such as Anthony Ludovici, insist that he is only an anti-feminist, not a misogynist.[2] Relationship with SaloméLou Andreas-Salomé, who knew Nietzsche very well, claimed that he had proposed to her (according to her, she refused him) and that there was something feminine in Nietzsche's "spiritual nature". According to her, Nietzsche considered genius to be a feminine genius.[3][clarification needed] [4] WritingsNietzsche wrote specifically about his views on women in Section VII of Human, All Too Human, which seems to hold women in high regard; but given some of his other comments, his overall attitude towards women is ambivalent. For instance, while in Human, All Too Human, he states that "the perfect woman is a higher type of human than the perfect man, and also something much more rare, " there are a number of contradictions and subtleties in Nietzsche's thought elsewhere which are not easily reconcilable. At times he could speak both in praise and in contempt of women, as in the following passage: "What inspires respect for woman, and often enough even fear, is her nature, which is more “natural” than man's, the genuine, cunning suppleness of a beast of prey, the tiger's claw under the glove, the naiveté of her egoism, her uneducatability and inner wildness, the incomprehensibility, scope, and movement of her desires and virtues." (Beyond Good and Evil, section 239.) His attitude can sometimes be entirely disparaging: "From the beginning, nothing has been more alien, repugnant, and hostile to woman than truth—her great art is the lie, her highest concern is mere appearance and beauty. " In section 6 in "Why I Write Such Excellent Books" of Ecce Homo, he claims that "goodness" in women is a sign of "physiological degeneration", and that women are on the whole cleverer and more wicked than men—which in Nietzsche's view, constitutes a compliment. Yet he goes on to claim that the feminist campaign for the emancipation of women was merely the resentment of some women against other women, who were physically better constituted and able to bear children. Other writings include: "Woman's love involves injustice and blindness against everything that she does not love... Woman is not yet capable of friendship: women are still cats and birds. Or at best cows... (Thus Spoke Zarathustra, On the Friend) "Woman! One-half of mankind is weak, typically sick, changeable, inconstant... she needs a religion of weakness that glorifies being weak, loving, and being humble as divine: or better, she makes the strong weak—she rules when she succeeds in overcoming the strong... Woman has always conspired with the types of decadence, the priests, against the 'powerful', the 'strong', the men-" (The Will to Power - 864, Second German edition of 1906) Philosophical influencesScholars of Aristotle have drawn comparisons between Aristotle's views on women and those of Nietzsche. They have argued that Nietzsche may have borrowed much of his political philosophy from the latter.[5] Degree of importanceView that misogynistic statements are significantKelly Oliver and Marilyn Pearsall have even suggested that Nietzsche's philosophy cannot be understood or analyzed apart from his remarks on women. They opine that, even though Nietzsche's work has been useful in the development of some feminist theory, it cannot be considered feminist per se: "While Nietzsche challenges traditional hierarchies between mind and body, reason and irrationality, nature and culture, truth and fiction — hierarchies that have been used to degrade and exclude women — his remarks about women and his use of feminine and maternal metaphors throughout his writings confound attempts simply to proclaim Nietzsche a champion of feminism or women."[6] Nietzsche's caveatingCornelia Klinger states in her book Continental Philosophy in Feminist Perspective: "Nietzsche, like Schopenhauer a prominent hater of women, at least relativizes his savage statements about woman-as-such."[7] One of Nietzsche's own statements is cited in support of this assertion:

Apparent misogyny as rhetorical strategyFrances Nesbitt Oppel interprets Nietzsche's attitude towards women as part of a rhetorical strategy.

Kathleen Merrow writes: "Nietzsche's metaphors of 'woman' — far from being misogynist — reveal a positive, affirmative 'woman.' His use of this metaphor radically dislocates traditional conceptions of the relationship masculine/feminine as it dislocates the 'truth' of metaphysics. I argue that the metaphor 'woman' is central to Nietzsche's attack on traditional philosophy and notions of truth."[9] Truly but self-critically misogynisticBabette Babich takes up this same quote as above, recognizing that "[a]lthough Nietzsche as generously as ever saves his commentators the labor of interpretation, the problem recurs precisely because of the nature of what he proceeds to call his truths." But instead of focusing on putative misogyny she opines:

References

Further readingMichael J. McNeal (editor) (2023). Nietzsche on Women and the Eternal-Feminine: A Critique of Truth and Values. Bloomsbury Academic. Caroline Joan S. Picart (1999). Resentment and the "Feminine" in Nietzsche's Politico-Aesthetics. Penn State University Press. Paul Patton (1993). Nietzsche, Feminism and Political Theory. Routledge. |