|

Fire-setting

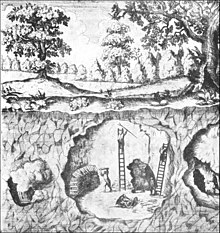

Fire-setting is a method of traditional mining used most commonly from prehistoric times up to the Middle Ages. Fires were set against a rock face to heat the stone, which was then doused with liquid, causing the stone to fracture by thermal shock. Rapid heating causes thermal shock by itself—without subsequent cooling—by producing different degrees of expansion in different parts of the rock (and in other materials). In practice, rapid cooling may or may not have been helpful to produce the desired effect. Some experiments have suggested that the water (or any other liquid) did not have a noticeable effect on the rock, but rather helped the miners' progress by quickly cooling down the area after the fire.[1][2] This technique was best performed in opencast mines where the smoke and fumes could dissipate safely. The technique was very dangerous in underground workings without adequate ventilation. The method became largely redundant with the growth in use of explosives. Although fire-setting was frequently used before modern times, it has been used sporadically since then. In some regions of the world, notably Africa and Eurasia, fire-setting continued to be in use until the 19th and 20th centuries.[3][4] It was used where rock was too hard to drill holes with steel borers for blasting or whenever it was economic because of cheapness of wood.[3] History  The oldest traces of this method in Europe were found in southern France (département of Hérault) and date back to the Copper Age.[5] Numerous finds exist from the Bronze Age, such as in the Alps, in the former mining district of Schwaz-Brixlegg in Tyrol,[6][7] or in the Goleen area in Cork,[8] to name a few. As for antique written sources, fire-setting is first described by Diodorus Siculus in his Bibliotheca historica written about 60 BC, about methods of mining used in ancient Egyptian gold mines. It is also mentioned in greater detail by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia, published in the first century AD. In Book XXXIII, he describes mining methods for gold, and the pursuit of the gold-bearing veins underground using tunnels and stopes. He mentions the use of vinegar to quench the hot rock, but water would have been just as effective, as vinegar was expensive at the time for regular use in a mine. The reference to vinegar may come from a description by Livy of Hannibal's crossing of the Alps, when it was said that the soldiers used vinegar in fire-setting to remove large rocks in the path of his army. The effectiveness of strong acetic acid solutions on heated limestone has been demonstrated in laboratory experiments.[9] Pliny also says that the method was used both in opencast and deep mining. This is confirmed by remains found at the Roman gold mine of Dolaucothi in west Wales, when modern miners broke into much older workings during the 1930s where they found wood ashes near worked rock faces. In another part of the mine, there are three adits at different heights which have been driven through barren rock to the gold-bearing veins for some considerable distance, and they would have provided drainage as well as ventilation to remove the smoke and hot gases during a fire-setting operation. They were certainly much larger in section than was normal for access galleries, and the draught of air through them would have been considerable. Fire-setting was used extensively during opencast mining, and is also described by Pliny in connection with the use of another mining technique known as hushing. Aqueducts were built to supply copious amounts of water to the minehead, where they were used to fill tanks and cisterns. The water was unleashed to scour the hillside below, both soil in the case of prospecting for metal veins, and then rock debris after a vein had been found. Fire-setting was used to break up the hard rocks of the vein and the surrounding barren rock, and was much safer to use in above ground workings since the smoke and fumes could dissipate more easily than in a confined space underground. Pliny also describes undermining methods that were used to facilitate the removal of hard rocks, and probably softer alluvial deposits as well.[9] Medieval EuropeThe method continued in use in the medieval period, and is described by Georg Agricola in his treatise on mining and mineral extraction, De re metallica. He warns about the problem of the "foetid vapours" and the need to evacuate the workings while the fires are lit, and presumably for some time afterwards until the gases and smoke had cleared. The problem raises the question of ventilation means in the mines, a problem often solved by ensuring that there was a continuous path for escape of the noxious fumes, perhaps aided by artificial ventilation. Agricola mentions the use of large water-powered bellows to create a draught, and continuity of workings to the surface were essential for a stream of air to run through them. In later times, a fire at the base of a shaft was used to create an updraught, but just like fire-setting, it was a hazardous and dangerous procedure, especially in collieries. As the number and complexity of the underground workings increased, care was needed to channel the air draught to all parts of the tunnels and faces. It was usually achieved by installing doors at key points. Most of the deaths in coal mine disasters were caused by inhalation of the toxic gases produced by firedamp explosions. The method continued in use for many years afterwards until finally made redundant by the use of explosives. However, they also produce toxic gases and care is needed to ensure good ventilation to remove those gases, like carbon monoxide, as well as choice of the explosive itself to minimise their emission.

See alsoReferences

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Fire-setting. |