|

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment (Amendment XV) to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government and each state from denying or abridging a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It was ratified on February 3, 1870,[1] as the third and last of the Reconstruction Amendments. In the final years of the American Civil War and the Reconstruction Era that followed, Congress repeatedly debated the rights of the millions of black freedmen. By 1869, amendments had been passed to abolish slavery and provide citizenship and equal protection under the laws, but the election of Ulysses S. Grant to the presidency in 1868 convinced a majority of Republicans that protecting the franchise of black male voters was important for the party's future. On February 26, 1869, after rejecting more sweeping versions of a suffrage amendment, Republicans proposed a compromise amendment which would ban franchise restrictions on the basis of race, color, or previous servitude. After surviving a difficult ratification fight and opposition from Democrats, the amendment was certified as duly ratified and part of the Constitution on March 30, 1870. According to the Library of Congress, in the House of Representatives 144 Republicans voted to approve the 15th Amendment, with zero Democrats in favor, 39 no votes, and seven abstentions. In the Senate, 33 Republicans voted to approve, again with zero Democrats in favor. United States Supreme Court decisions in the late nineteenth century interpreted the amendment narrowly. From 1890 to 1910, the Democratic Party in the Southern United States adopted new state constitutions and enacted "Jim Crow" laws that raised barriers to voter registration. This resulted in most black voters and many Poor Whites being disenfranchised by poll taxes and literacy tests, among other barriers to voting, from which white male voters were exempted by grandfather clauses. A system of white primaries and violent intimidation by Democrats through the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) also suppressed black participation. Although the fifteenth amendment is “self-executing” the court early emphasized that the right granted to be free from racial discrimination should be kept free and pure by congressional enactment whenever necessary.[2] In the twentieth century, the Court began to interpret the amendment more broadly, striking down grandfather clauses in Guinn v. United States (1915) and dismantling the white primary system created by the Democratic Party in the "Texas primary cases" (1927–1953). Voting rights were further incorporated into the Constitution in the Nineteenth Amendment (voting rights for women, effective 1920), the Twenty-fourth Amendment (prohibiting poll taxes in federal elections, effective 1964) and the Twenty-sixth Amendment (lowering the voting age from 21 to 18, effective 1971). The Voting Rights Act of 1965 provided federal oversight of elections in discriminatory jurisdictions, banned literacy tests and similar discriminatory devices, and created legal remedies for people affected by voting discrimination. The Court also found poll taxes in state elections unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections (1966). Text

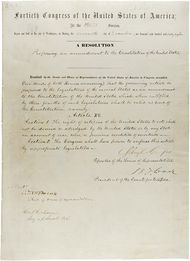

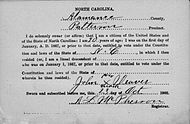

BackgroundIn the final years of the American Civil War and the Reconstruction Era that followed, Congress repeatedly debated the rights of black former slaves freed by the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and the 1865 Thirteenth Amendment, the latter of which had formally abolished slavery. Following the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment by Congress, however, Republicans grew concerned over the increase it would create in the congressional representation of the Democratic-dominated Southern states. Because the full population of freed slaves would be now counted rather than the three-fifths mandated by the previous Three-Fifths Compromise, the Southern states would dramatically increase their power in the population-based House of Representatives.[4] Republicans hoped to offset this advantage by attracting and protecting votes of the newly enfranchised black population.[5][6][7] In 1865, Congress passed what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1866, guaranteeing citizenship without regard to race, color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude. The bill also guaranteed equal benefits and access to the law, a direct assault on the Black Codes passed by many post-war Southern states. The Black Codes attempted to return ex-slaves to something like their former condition by, among other things, restricting their movement, forcing them to enter into year-long labor contracts, prohibiting them from owning firearms, and by preventing them from suing or testifying in court.[8] Although strongly urged by moderates in Congress to sign the bill, President Johnson vetoed it on March 27, 1866. In his veto message, he objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the freedmen at a time when 11 out of 36 states were unrepresented in the Congress, and that it allegedly discriminated in favor of African Americans and against whites.[9][10] Three weeks later, Johnson's veto was overridden and the measure became law. Despite this victory, even some Republicans who had supported the goals of the Civil Rights Act began to doubt that Congress possessed the constitutional power to turn those goals into laws.[11][12] The experience encouraged both radical and moderate Republicans to seek Constitutional guarantees for black rights, rather than relying on temporary political majorities.[13] On June 18, 1866, Congress adopted the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed citizenship and equal protection under the laws regardless of race, and sent it to the states for ratification. After a bitter struggle that included attempted rescissions of ratification by two states, the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted on July 28, 1868.[14] Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment punished, by reduced representation in the House of Representatives, any state that disenfranchised any male citizens over 21 years of age. By failing to adopt a harsher penalty, this signaled to the states that they still possessed the right to deny ballot access based on race.[15] Northern states were generally as averse to granting voting rights to blacks as Southern states. In the year of its ratification, only eight Northern states allowed blacks to vote.[16] In the South, blacks were able to vote in many areas, but only through the intervention of the occupying Union Army.[17] Before Congress had granted suffrage to blacks in the territories by passing the Territorial Suffrage Act on January 10, 1867 (Source: Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 2nd Session, pp. 381-82),[18][19] blacks were granted the right to vote in the District of Columbia on January 8, 1867.[20] Proposal and ratificationProposal Anticipating an increase in Democratic membership in the following Congress, Republicans used the lame-duck session of the 40th United States Congress to pass an amendment protecting black suffrage.[21] Representative John Bingham, the primary author of the Fourteenth Amendment, pushed for a wide-ranging ban on suffrage limitations, but a broader proposal banning voter restriction on the basis of "race, color, nativity, property, education, or religious beliefs" was rejected.[22] A proposal to specifically ban literacy tests was also rejected.[21] Some Representatives from the North, where nativism was a major force, wished to preserve restrictions denying the franchise to foreign-born citizens, as did Representatives from the West, where ethnic Chinese people were banned from voting.[22] Both Southern and Northern Republicans also wanted to continue to deny the vote temporarily to Southerners disenfranchised for support of the Confederacy, and they were concerned that a sweeping endorsement of suffrage would enfranchise this group.[23] A House and Senate conference committee proposed the amendment's final text, which banned voter restriction only on the basis of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."[3] To attract the broadest possible base of support, the amendment made no mention of poll taxes or other measures to block voting, and did not guarantee the right of blacks to hold office.[24] Preliminary drafts did include officeholding language, but scholars disagree as to the reason for this change.[25] This compromised proposal was approved by the House on February 25, 1869, and the Senate the following day.[26][27] The vote in the House was 144 to 44, with 35 not voting. The House vote was almost entirely along party lines, with no Democrats supporting the bill and only 3 Republicans voting against it,[28] some because they thought the amendment did not go far enough in its protections.[27][29] The House of Representatives passed the amendment, with 143 Republicans and one Conservative Republican voting "Yea" and 39 Democrats, three Republicans, one Independent Republican and one Conservative voting "No"; 26 Republicans, eight Democrats, and one Independent Republican did not vote.[30] The final vote in the Senate was 39 to 13, with 14 not voting.[31] The Senate passed the amendment, with 39 Republicans voting "Yea" and eight Democrats and five Republicans voting "Nay"; 13 Republicans and one Democrat did not vote.[32] Some Radical Republicans, such as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, abstained from voting because the amendment did not prohibit literacy tests and poll taxes.[33] Following congressional approval, the proposed amendment was then sent by Secretary of State William Henry Seward to the states for ratification or rejection.[27] Ratification Though many of the original proposals for the amendment had been moderated by negotiations in committee, the final draft nonetheless faced significant hurdles in being ratified by three-fourths of the states. Historian William Gillette wrote of the process, "it was hard going and the outcome was uncertain until the very end."[21] One source of opposition to the proposed amendment was the women's suffrage movement, which before and during the Civil War had made common cause with the abolitionist movement. State constitutions often connected race and sex by limiting suffrage to "white male citizens."[25] However, with the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, which had explicitly protected only male citizens in its second section, activists found the civil rights of women divorced from those of blacks.[15] Matters came to a head with the proposal of the Fifteenth Amendment, which barred race discrimination but not sex discrimination in voter laws. One of Congress's most explicit discussions regarding the link between suffrage and officeholding occurred during discussions about the Fifteenth Amendment.[25] Initially, both houses passed a version of the amendment that included language referring to officeholding but ultimately the language was omitted.[25] During this time, women continued to advocate for their own rights, holding conventions and passing resolutions demanding the right to vote and hold office.[25] Some preliminary versions of the amendment even included women.[25] However, the final version omitted references to sex, further splintering the women's suffrage movement.[25] After an acrimonious debate, the American Equal Rights Association, the nation's leading suffragist group, split into two rival organizations: the National Woman Suffrage Association of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who opposed the amendment, and the American Woman Suffrage Association of Lucy Stone and Henry Browne Blackwell, who supported it. The two groups remained divided until the 1890s.[36]  Nevada was the first state to ratify the amendment, on March 1, 1869.[27] The New England states and most Midwest states also ratified the amendment soon after its proposal.[21] Southern states still controlled by Radical reconstruction governments, such as North Carolina, also swiftly ratified.[26] Newly elected President Ulysses S. Grant strongly endorsed the amendment, calling it "a measure of grander importance than any other one act of the kind from the foundation of our free government to the present day." He privately asked Nebraska's governor to call a special legislative session to speed the process, securing the state's ratification.[21] In April and December 1869, Congress passed Reconstruction bills mandating that Virginia, Mississippi, Texas and Georgia ratify the amendment as a precondition to regaining congressional representation; all four states did so.[27] The struggle for ratification was particularly close in Indiana and Ohio, which voted to ratify in May 1869 and January 1870, respectively.[21][27] New York, which had ratified on April 14, 1869, tried to revoke its ratification on January 5, 1870. However, in February 1870, Georgia, Iowa, Nebraska, and Texas ratified the amendment, bringing the total ratifying states to twenty-nine—one more than the required twenty-eight ratifications from the thirty-seven states, and forestalling any court challenge to New York's resolution to withdraw its consent.[27] The first twenty-eight states to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment were:[37]

Secretary of State Hamilton Fish certified the amendment on March 30, 1870,[27][39] also including the ratifications of: The remaining seven states all subsequently ratified the amendment:[40]

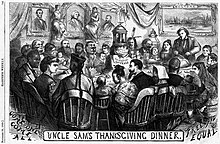

The amendment's adoption was met with widespread celebrations in black communities and abolitionist societies; many of the latter disbanded, feeling that black rights had been secured and their work was complete. President Grant said of the amendment that it "completes the greatest civil change and constitutes the most important event that has occurred since the nation came to life."[21] Many Republicans felt that with the amendment's passage, black Americans no longer needed federal protection; congressman and future president James A. Garfield stated that the amendment's passage "confers upon the African race the care of its own destiny. It places their fortunes in their own hands."[24] Congressman John R. Lynch later wrote that ratification of those two amendments made Reconstruction a success.[42] ApplicationIn the year of the 150th anniversary of the Fifteenth Amendment Columbia University history professor and historian Eric Foner said about the Fifteenth Amendment as well as its history during the Reconstruction era and Post-Reconstruction era:

Reconstruction African Americans called the amendment the nation's "second birth" and a "greater revolution than that of 1776," according to historian Eric Foner in his book The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution.[43] The first black person known to vote after the amendment's adoption was Thomas Mundy Peterson, who cast his ballot on March 31, 1870, in a Perth Amboy, New Jersey, referendum election adopting a revised city charter.[44] African Americans—many of them newly freed slaves—put their newfound freedom to use, voting in scores of black candidates. During Reconstruction, 16 black men served in Congress and 2,000 black men served in elected local, state, and federal positions.[43] White supremacists, such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), used paramilitary violence to prevent blacks from voting. The Enforcement Acts were passed by Congress in 1870–1871 to authorize federal prosecution of the KKK and others who violated the amendment.[45] In United States v. Reese (1876),[46] the first U.S. Supreme Court decision interpreting the Fifteenth Amendment, the Court interpreted the amendment narrowly, upholding ostensibly race-neutral limitations on suffrage, including poll taxes, literacy tests, and a grandfather clause that exempted citizens from other voting requirements if their grandfathers had been registered voters.[47][48] The Court also stated that the amendment does not confer the right of suffrage, but it invests citizens of the United States with the right of exemption from discrimination in the exercise of the elective franchise on account of their race, color, or previous condition of servitude, and empowers Congress to enforce that right by "appropriate legislation".[49] The Court wrote:

A number of blacks were killed at the Colfax massacre of 1873 while attempting to defend their right to vote. In United States v. Cruikshank (1876, decided the same day as Reese), the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government did not have the authority to prosecute the perpetrators of the Colfax massacre because they were not state actors.[50][51] In 1877, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was elected president after a highly contested election, receiving support from three Southern states in exchange for a pledge to allow white Democratic governments to rule without federal interference. As president, he refused to enforce federal civil rights protections, allowing states to begin to implement racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws. Federal troops were withdrawn and prosecutions under the Enforcement Acts dropped significantly. [52] Post-ReconstructionIn Ex Parte Yarbrough (1884), the Court allowed individuals who were not state actors to be prosecuted because Article I, Section 4, gives Congress the power to regulate federal elections. A Federal Elections Bill (the Lodge Bill of 1890) was successfully filibustered in the Senate.[53] Congress further weakened the Enforcement Acts in 1894 by removing a provision against conspiracy.[51] From 1890 to 1910, poll taxes and literacy tests were instituted across the South, effectively disenfranchising the great majority of black men. White male-only primary elections also served to reduce the influence of black men in the political system. Along with increasing legal obstacles, blacks were excluded from the political system by threats of violent reprisals by whites in the form of lynch mobs and terrorist attacks by the Ku Klux Klan.[47] Some Democrats even advocated a repeal of the amendment, such as William Bourke Cockran of New York.[54] In the 20th century, the Court began to read the Fifteenth Amendment more broadly.[51] In Guinn v. United States (1915),[55] a unanimous Court struck down an Oklahoma grandfather clause that effectively exempted white voters from a literacy test, finding it to be discriminatory. The Court ruled in the related case Myers v. Anderson (1915), that the officials who enforced such a clause were liable for civil damages.[56][57] The Court addressed the white primary system in a series of decisions later known as the "Texas primary cases". In Nixon v. Herndon (1927),[58] Dr. Lawrence A. Nixon sued for damages under federal civil rights laws after being denied a ballot in a Democratic party primary election on the basis of race. The Court found in his favor on the basis of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal protection under the law, while not discussing his Fifteenth Amendment claim.[59] After Texas amended its statute to allow the political party's state executive committee to set voting qualifications, Nixon sued again; in Nixon v. Condon (1932),[60] the Court again found in his favor on the basis of the Fourteenth Amendment.[61] Following Nixon, the Democratic Party's state convention instituted a rule that only whites could vote in its primary elections; the Court unanimously upheld this rule as constitutional in Grovey v. Townsend (1935), distinguishing the discrimination by a private organization from that of the state in the previous primary cases.[62][63] However, in United States v. Classic (1941),[64] the Court ruled that primary elections were an essential part of the electoral process, undermining the reasoning in Grovey. Based on Classic, the Court in Smith v. Allwright (1944),[65] overruled Grovey, ruling that denying non-white voters a ballot in primary elections was a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment.[66] In the last of the Texas primary cases, Terry v. Adams (1953),[67] the Court ruled that black plaintiffs were entitled to damages from a group that organized whites-only pre-primary elections with the assistance of Democratic party officials.[68]  The Court also used the amendment to strike down a gerrymander in Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1960).[69] The decision found that the redrawing of city limits by Tuskegee, Alabama officials to exclude the mostly black area around the Tuskegee Institute discriminated on the basis of race.[51][70] The Court later relied on this decision in Rice v. Cayetano (2000),[71] which struck down ancestry-based voting in elections for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs; the ruling held that the elections violated the Fifteenth Amendment by using "ancestry as a racial definition and for a racial purpose".[72] After judicial enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment ended grandfather clauses, white primaries, and other discriminatory tactics, Southern black voter registration gradually increased, rising from five percent in 1940 to twenty-eight percent in 1960.[51] Although the Fifteenth Amendment was never interpreted to prohibit poll taxes, in 1962 the Twenty-fourth Amendment was adopted banning poll taxes in federal elections, and in 1966 the Supreme Court ruled in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections (1966)[73] that state poll taxes violate the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause.[74][75] Congress used its authority pursuant to Section 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965, achieving further racial equality in voting. Sections 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act required states and local governments with histories of racial discrimination in voting to submit all changes to their voting laws or practices to the federal government for approval before they could take effect, a process called "preclearance". By 1976, sixty-three percent of Southern blacks were registered to vote, a figure only five percent less than that for Southern whites.[51] The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Sections 4 and 5 in South Carolina v. Katzenbach (1966). However, in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the Supreme Court ruled that Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act, which established the coverage formula that determined which jurisdictions were subject to preclearance, was no longer constitutional and exceeded Congress's enforcement authority under Section 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment. The Court declared that the Fifteenth Amendment "commands that the right to vote shall not be denied or abridged on account of race or color, and it gives Congress the power to enforce that command. The Amendment is not designed to punish for the past; its purpose is to ensure a better future."[76] According to the Court, "Regardless of how to look at the record no one can fairly say that it shows anything approaching the 'pervasive', 'flagrant', 'widespread', and 'rampant' discrimination that faced Congress in 1965, and that clearly distinguished the covered jurisdictions from the rest of the nation." In dissent, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote, "Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet."[77][78] While the preclearance provision itself was not struck down, it will continue to be inoperable unless Congress passes a new coverage formula.[76][79] See also

ReferencesInformational notes Citations

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. |