|

Business Plot

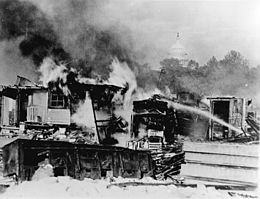

The Business Plot, also called the Wall Street Putsch[1] and the White House Putsch, was a political conspiracy in 1933, in the United States, to overthrow the government of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and install Smedley Butler as dictator.[2][3] Butler, a retired Marine Corps major general, testified under oath that wealthy businessmen were plotting to create a fascist veterans' organization with him as its leader and use it in a coup d'état to overthrow Roosevelt. In 1934, Butler testified under oath before the United States House of Representatives Special Committee on Un-American Activities (the "McCormack–Dickstein Committee") on these revelations.[4] Although no one was prosecuted, the congressional committee final report said, "there is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient." Early in the committee's gathering of testimony most major news media dismissed the plot, with a New York Times editorial characterizing it as a "gigantic hoax".[5] When the committee's final report was released, the Times said the committee "purported to report that a two-month investigation had convinced it that General Butler's story of a Fascist march on Washington was alarmingly true" and "... also alleged that definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington, which was to have been led by Major Gen. Smedley D. Butler, retired, according to testimony at a hearing, was actually contemplated".[6] The individuals involved all denied the existence of a plot. While historians have questioned whether a coup was actually close to execution, most agree that some sort of "wild scheme" was contemplated and discussed.[7][8][9][10] BackgroundButler and the veterans On July 17, 1932, thousands of World War I veterans converged on Washington, D.C., set up tent camps, and demanded immediate payment of bonuses due to them according to the World War Adjusted Compensation Act of 1924 (which made certain bonuses initially due no earlier than 1925 and all no later than 1945). Walter W. Waters, a former Army sergeant, led this "Bonus Army".[citation needed] It was encouraged by an appearance from retired Marine Corps Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler, a popular military figure of the time.[11] A few days after Butler's arrival, President Herbert Hoover ordered the marchers removed and U.S. Army cavalry troops under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur destroyed their camps.[citation needed] Butler, although a self-described Republican, responded by supporting Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 US presidential election.[12] By 1933, Butler started denouncing capitalism and bankers, going on to explain that for 33 years he had been a "high-class muscle man" for Wall Street, the bankers and big business, labeling himself as a "racketeer for Capitalism".[13] Reaction to RooseveltRoosevelt's election was upsetting for many conservative businessmen of the time, as his "campaign promise that the government would provide jobs for all the unemployed had the reverse effect of creating a new wave of unemployment by businessmen frightened by fears of socialism and reckless government spending".[14] Some writers have said concerns over the gold standard were also involved; Jules Archer, in The Plot to Seize the White House, wrote that with the end of the gold standard, "conservative financiers were horrified. They viewed a currency not solidly backed by gold as inflationary, undermining both private and business fortunes and leading to national bankruptcy. Roosevelt was damned as a socialist or Communist out to destroy private enterprise by sapping the gold backing of wealth in order to subsidize the poor."[15] McCormack–Dickstein CommitteeThe McCormack–Dickstein Committee began examining evidence of an alleged plot on November 20, 1934. On November 24, the committee released a statement detailing the testimony it had heard and its preliminary findings. On February 15, 1935, the committee submitted its final report to the House of Representatives.[16] During the committee hearings, Butler testified that Gerald C. MacGuire attempted to recruit him to lead a coup, promising him an army of 500,000 men for a march on Washington, D.C., and financial backing. Butler testified that the pretext for the coup would be that the president's health was failing.[17] Despite Butler's support for Roosevelt in the election[12] and his reputation as a strong critic of capitalism,[18] Butler said the plotters felt his good reputation and popularity were vital in attracting support amongst the general public and saw him as easier to manipulate than others. Given a successful coup, Butler said that the plan was for him to have held near-absolute power in the newly created position of "Secretary of General Affairs", while Roosevelt would have assumed a figurehead role.[19] Those implicated in the plot by Butler all denied any involvement. MacGuire was the only figure identified by Butler who testified before the committee. Others whom Butler accused were not called to testify because the "committee has had no evidence before it that would in the slightest degree warrant calling before it such men ... The committee will not take cognizance of names brought into testimony which constitute mere hearsay."[20] On the final day of the committee,[21] January 29, 1935, John L. Spivak published the first of two articles in the Communist magazine New Masses, revealing portions of testimony to the committee that had been redacted as hearsay. Spivak argued that the plot was part of a plan by J. P. Morgan and other financiers who were coordinating with fascist groups to overthrow Roosevelt.[22] Historian Hans Schmidt concludes that while Spivak made a cogent argument for taking the suppressed testimony seriously, he embellished his article with his "overblown" claims regarding Jewish financiers, which Schmidt dismisses as guilt by association not supported by the evidence of the Butler-MacGuire conversations themselves.[23] On March 25, 1935, MacGuire died in a hospital in New Haven, Connecticut, at the age of 36. His attending doctor at the hospital attributed the death to pneumonia and its complications, but also said that the accusations against MacGuire had led to his weakened condition and collapse which in turn led to the pneumonia.[24] Butler's testimony in detail1933On July 1, 1933, Butler met with MacGuire and Bill Doyle for the first time. MacGuire was a $100-a-week bond salesman for Wall Street banking firm Grayson Murphy & Company[25][26] and a member of the Connecticut American Legion.[27][28] Doyle was commander of the Massachusetts American Legion.[27] Butler stated that he was asked to run for National Commander of the American Legion.[29] On July 3 or 4, Butler held a second meeting with MacGuire and Doyle. He stated that they offered to get hundreds of supporters at the American Legion convention to ask for a speech.[30] MacGuire left a typewritten speech with Butler that they proposed he read at the convention. "It urged the American Legion convention to adopt a resolution calling for the United States to return to the gold standard, so that when veterans were paid the bonus promised to them, the money they received would not be worthless paper."[15] The inclusion of this demand further increased Butler's suspicion.[citation needed] Around August 1, MacGuire visited Butler alone. Butler stated that MacGuire told him Grayson Murphy underwrote the formation of the American Legion in New York, and Butler told MacGuire that the American Legion was "nothing but a strikebreaking outfit."[31] Butler never saw Doyle again.[citation needed] On September 24,[32][33] MacGuire visited Butler's hotel room in Newark.[34] In late September Butler met with Robert Sterling Clark.[35] Clark was an art collector and an heir to the Singer Corporation fortune.[36][37] MacGuire had known Clark when Clark was a second lieutenant in China during the Boxer Rebellion, where he had been nicknamed "the millionaire lieutenant".[37] 1934During the first half of 1934, MacGuire traveled to Europe and mailed postcards to Butler.[38] On March 6, MacGuire wrote Clark and Clark's attorney a letter describing the Croix-de-Feu,[39] a nationalist French league of the Interwar period.[citation needed] On August 22, Butler met MacGuire at a hotel, the last time Butler met him.[40][41] According to Butler's account, it was on this occasion that MacGuire asked Butler to run a new veterans' organization and lead a coup attempt against the President.[citation needed] On September 13, Paul Comly French, a reporter who had once been Butler's personal secretary,[42] met MacGuire in his office.[43] In late September, Butler told Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) commander James E. Van Zandt that co-conspirators would be meeting him at an upcoming Veterans of Foreign Wars convention.[citation needed] On November 20 the committee began examining evidence. French broke the story in the Philadelphia Record and the New York Post on November 21.[44] On November 22, The New York Times wrote its first article on the story and described it as a "gigantic hoax".[5][45] Committee reportsThe Congressional committee preliminary report of November 24, 1934 said:

The congressional committee final report, released on February 15, 1935, said:

Contemporaneous reactionOn November 21, 1934, one day into the committee gathering testimony, The New York Times ran an article with the headline, "Gen. Butler Bares 'Fascist Plot' To Seize Government by Force; Says Bond Salesman, as Representative of Wall St. Group, Asked Him to Lead Army of 500,000 in March on Capital – Those Named Make Angry Denials – Dickstein Gets Charge".[47] The Philadelphia Record also reported on the story on November 21 and 22, 1934.[citation needed] A November 22, 1934, New York Times editorial published just two days into committee testimony dismissed Butler's story as "a gigantic hoax" and a "bald and unconvincing narrative."[5][45] Time magazine reported on December 3, 1934, that the committee "alleged that definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington, which was to have been led by Maj. Gen. Smedley D. Butler, retired, according to testimony at a hearing, was actually contemplated".[6] Thomas W. Lamont of J.P. Morgan & Co. called it "perfect moonshine."[45][when?] Gen. Douglas MacArthur, alleged to be the back-up leader if Butler declined, referred to it as "the best laugh story of the year."[45] By February 16, 1935, one day after the committee had released its final report, The New York Times had changed its tone, running on page one the headline: "Asks Laws To Curb Foreign Agitators; Committee In Report To House Attacks Nazis As The Chief Propagandists In Nation. State Department Acts Checks Activities Of An Italian Consul – Plan For March On Capital Is Held Proved." The article stated, "It also alleged that definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington, which was to have been led by Major. Gen. Smedley D. Butler, retired, according to testimony at a hearing, was actually contemplated. The committee recalled testimony by General Butler, saying he had testified that Gerald C. MacGuire had tried to persuade him to accept the leadership of a Fascist army."[48] Separately, VFW commander James E. Van Zandt stated to the press, "Less than two months" after Gen. Butler warned him, "he had been approached by 'agents of Wall Street' to lead a Fascist dictatorship in the United States under the guise of a 'Veterans Organization'."[49] Later reactionsPulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. said in 1958, "Most people agreed with Mayor La Guardia of New York in dismissing it as a 'cocktail putsch'".[50] In Schlesinger's summation of the affair in 1958, "No doubt, MacGuire did have some wild scheme in mind, though the gap between contemplation and execution was considerable, and it can hardly be supposed that the Republic was in much danger."[10] Historian Robert F. Burk wrote, "At their core, the accusations probably consisted of a mixture of actual attempts at influence peddling by a small core of financiers with ties to veterans organizations and the self-serving accusations of Butler against the enemies of his pacifist and populist causes."[7] Historian Hans Schmidt wrote, "Even if Butler was telling the truth, as there seems little reason to doubt, there remains the unfathomable problem of MacGuire's motives and veracity. He may have been working both ends against the middle, as Butler at one point suspected. In any case, MacGuire emerged from the HUAC hearings as an inconsequential trickster whose base dealings could not possibly be taken alone as verifying such a momentous undertaking. If he was acting as an intermediary in a genuine probe, or as agent provocateur sent to fool Butler, his employers were at least clever enough to keep their distance and see to it that he self-destructed on the witness stand."[8] Prescott BushIn July 2007, a BBC investigation reported that Prescott Bush, father of U.S. President George H. W. Bush and grandfather of then-president George W. Bush, was to have been a "key liaison" between the 1933 Business Plotters and the newly emerged Nazi regime in Germany,[51] although this has been disputed by Jonathan Katz as a misconception caused by a clerical research error.[52] According to Katz, "Prescott Bush was too involved with the actual Nazis to be involved with something that was so home grown as the Business Plot."[53] Film adaptationsCity of Angels, Stephen J. Cannell’s 1976 television detective series set in 1930s Los Angeles, featured a three-part pilot (later released separately on VHS and DVD), "The November Plan," loosely based on the Business Plot.[54] The Business Plot inspired the 2022 comedy mystery film, Amsterdam, written and directed by American filmmaker David O. Russell, starring Christian Bale, Margot Robbie and John David Washington as a trio of protagonists who uncover the conspiracy and prevent it from materializing.[55] General Gil Dillenbeck, played by Robert De Niro, is based on Major General Smedley Butler. During the end of the film, a clip of Dillenbeck speaking before the congressional committee is played alongside footage of Butler's actual testimony, revealing it to be the same speech.[56] See alsoReferencesCitations

Works cited

External linksWikisource has original text related to this article:

|