|

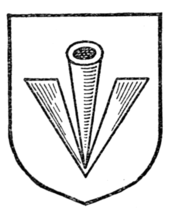

Broad arrow  The broad arrow, of which the pheon is a variant, is a stylised representation of a metal arrowhead, comprising a tang and two barbs meeting at a point. It is a symbol used traditionally in heraldry, most notably in England, and later by the British government to mark government property. It became particularly associated with the Board of Ordnance, and later the War Department and the Ministry of Defence. It was exported to other parts of the British Empire, where it was used in similar official contexts. It is sometimes nicknamed the crows foot.[1] In heraldry, the arrowhead generally points downwards, whereas in other contexts it more usually points upwards. In heraldry The broad arrow as a heraldic device comprises a socket tang with two converging blades, or barbs. When these barbs are engrailed on their inner edges, the device may be termed a pheon. Woodward's Treatise on Heraldry: British and Foreign with English and French Glossaries (1892), makes the following distinction: "A BROAD ARROW and a PHEON are represented similarly, except that the Pheon has its inner edges jagged, or engrailed."[2] Parker's Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry (1894) likewise states, "A broad arrow differs somewhat ... and resembles a pheon, except in the omission of the jagged edge on the inside of the barbs."[3] However, A. C. Fox-Davies, in his Complete Guide to Heraldry (1909), comments: "This is not a distinction very stringently adhered to."[4] The pheon features prominently in the arms of the Sidney family of Penshurst, and thence in the arms of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, and of Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia. Sidney Sussex's newsletter for alumni is titled Pheon.[5] Use for British Government property   The broad arrow was used in England (and later Britain), apparently from the early 14th century, and more widely from the 16th century, to mark objects purchased from the monarch's money, or to indicate government property. It became particularly associated with the Office or Board of Ordnance, the principal duty of which was to supply guns, ammunition, stores and equipment to the King's Navy. OriginsThe origins of the broad arrow device used by the Board of Ordnance are debated. The symbol is widely supposed to have been derived from the pheon in the arms of the Sidney family, through the influence either of Sir Philip Sidney, who served as Joint Master-General of the Ordnance in 1585–6; or that of his great-nephew, Henry Sydney, 1st Earl of Romney, who served as Master-General from 1693 to 1702.[6][7][8] However, as noted by the Oxford English Dictionary, "this is not supported by the evidence", as the use of the device predates the association of either Sidney with the Board.[9] The earliest known use of the symbol in what seems to be an official capacity is in 1330, on the seal used by Richard de la Pole as butler to King Edward III.[10][11] In 1383, it is recorded that a member of the butlery staff, having selected a pipe of wine for the King's use, "signo regio capiti sagitte consimili signavit" ("marked it with the royal sign like an arrowhead").[10] In 1386, Thomas Stokes was condemned to stand in the pillory by the Court of Aldermen of London for the offence of having impersonated an officer of the royal household, in which role he had commandeered several barrels of ale from brewers, marking them with a symbol referred to as an "arewehead".[12] The device was also used in the 15th and 16th centuries as an assay mark for pewter and tin.[10] An alternative theory is that the device used on naval stores and property was in its origins a simplified and corrupted version of an anchor symbol.[13] Thus, a set of "Instructions for marking of Timber for His Majesty's Navy" issued in 1609 commands:

Later useA letter sent by Thomas Gresham to the Privy Council in 1554, relating to the shipment of 50 cases of Spanish reals (coins) from Seville to England, explained that each case was "marked with the broad arrow and numbered from 1 to 50".[15] A proclamation of Charles I issued in 1627 ordered that tobacco imported to England from non-English plantations should be sealed with "a seale engraven with a broad Arrow and a Portcullice".[16] A proclamation issued by Charles II in 1661 ran:

An Order in Council of 1664, relating to the requisitioning of merchant ships for naval use, similarly authorised the Commissioners of the Navy "to put the broad arrow on any ship in the River they had a mind to hire, and fit them out for sea";[17] while the Embezzlement of Public Stores Act 1697 (9 Will. 3. c. 41) sought to prevent the theft of military and naval property by prohibiting anyone other than official contractors from marking "any Stores of War or Naval Stores whatsoever, with the Marks usually used to and marked upon His Majesties said Warlike and Naval or Ordnance Stores; ... [including] any other Stores with the Broad Arrow by Stamp Brand or otherwise".[17]  From the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, the broad arrow regularly appeared on military boxes and equipment such as canteens, bayonets and rifles. The prisons built by the Admiralty for the French Revolutionary Wars were equipped with mattresses and other items bearing the broad arrow: at Norman Cross Prison, Huntingdonshire, this was proven effective, when a local tradesman found in possession of items bearing the marks was convicted and sentenced to stand in the pillory and two years in a house of correction.[18] The broad arrow was routinely used on British prison uniforms from about the 1830s onwards.[19] An instance of the Admiralty using the mark in a salvage case occurred at Wisbech, Isle of Ely in 1860: "The barque Angelo C, laden with barley, from Sulina, lying at Mr Morton's granary, has been marked with the 'broad arrow', a writ at Admiralty having been issued at the instance of Peter Pilkington, one of the pilots of this port, who claims £400 for salvage services alleged to have been rendered to the vessel during the great gale of the 28th ult."[20]  Topped with a horizontal line, the broad arrow was widely used on Ordnance Survey benchmarks.[21] Broad arrow marks were also used by Commonwealth countries on their ordnance. The Board of Ordnance was absorbed into the War Department in 1855, but the broad arrow continued to be used by its successor bodies: the War Department 1855–57, the War Office 1857–1964, and by the Ministry of Defence from 1964 onwards, before being phased out in the 1980s. LegalityIt is currently a criminal offence in the United Kingdom to reproduce the broad arrow without authority (in the same way as it is an offence to reproduce hallmarks). Section 4 of the Public Stores Act 1875 makes it illegal to use the "broad arrow" on any goods without permission.[22][23] NewspaperA newspaper, The Broad Arrow, including the broad arrow symbol in its masthead, and described as "A Paper for the Services", was published from 1833. Its title was later extended to include The Naval and Military Gazette. During the First World War it was printed by W. H. Smith & Son. It later became The Army, Navy and Air Force Gazette: incorporating "The Broad Arrow" and "Naval and Military Gazette". In 1936, it merged with the Naval and Military Record to form the United Services Review.[24] Surplus material Items deemed no longer serviceable, but still of market value, were stamped again with a second broad arrow, nose-to-nose with the first, to mark them as legally "sold out of service".[25] In the American coloniesThe broad arrow was used by the British to mark trees (one species of which was the eastern white pine) intended for ship building use in North America during colonial times. Three axe strikes, resembling an arrowhead and shaft, were marked on large mast-grade trees.[26] Use of the broad arrow mark commenced in earnest in 1691 with the Massachusetts Charter, which contained a Mast Preservation Clause specifying, in part:[27]

Initially England imported its mast trees from the Baltic states, but it was an expensive, lengthy and politically treacherous proposition. Much of British naval policy at the time revolved around keeping the trade route to the Baltics open. With Baltic timber becoming less appealing to use, the Admiralty's eye turned towards the Colonies. Colonists paid little attention to the Charter's Mast Preservation Clause, and tree harvesting increased with disregard for broad arrow protected trees. However, as Baltic imports decreased, the British timber trade increasingly depended on North American trees, and enforcement of broad arrow policies increased.[28] Persons appointed to the position of Surveyor-General of His Majesty's Woods were responsible for selecting, marking and recording trees as well as policing and enforcing the unlicensed cutting of protected trees. This process was open to abuse, and the British monopoly was very unpopular with colonists. Part of the reason was that many protected trees were on either town-owned or privately owned lands. Colonists could only sell mast trees to the British, but were substantially underpaid for the lumber. Even though it was illegal for the colonists to sell to enemies of the crown, both the French and the Spanish were in the market for mast trees as well and would pay a much better price. Acts of Parliament in 1711, 1722 and 1772 (Timber for the Navy Act 1772) extended protection finally to 12-inch-diameter (300 mm) trees and resulted in the Pine Tree Riot that same year. This was one of the first acts of rebellion by the American colonists leading to the American Revolution in 1775, and a flag bearing a white pine is said[by whom?] to have been flown at the Battle of Bunker Hill. In Australia The broad arrow was used to denote government property in the Australian colonies[29] from the earliest times of settlement[30] until well after federation.[31] William Oswald Hodgkinson's government-sponsored North-West Expedition in Queensland used the broad arrow to mark trees along the expedition's route.[32] The broad arrow mark was also used on survey markers.[33] It can still be seen on some Australian military property. The broad arrow brand is also still used to mark trees as the property of the Crown, and is protected against unauthorised use. In Victoria, Australia for example, Part 4 of the Forests (Licences and Permits) Regulations 2009 states that "an authorised officer may use the broad arrow brand ... to mark trees in a timber harvesting area which are not to be felled; or to indicate forest produce which has been seized under the Act; or to indicate that forest produce lawfully cut or obtained is not to be removed until the brand is obliterated with the crown brand by any authorised officer."[34] The broad arrow is used currently by the Australian Army to denote property owned by the Department of Defence.[35] The mark was not widely used for convict clothing in Australia during the early period of transportation, as government-issued uniforms were rare.[36] The Board of Ordnance took over supply in the 1820s, and uniforms from this period onwards were generally marked with the broad arrow,[37] including so-called "magpie" uniforms.[38] In an account published in 1827, Peter Miller Cunningham described Australian convicts as wearing "white woollen Paramatta frocks and trowsers, or grey and yellow jackets with duck overalls, (the different styles of dress denoting the oldness or newness of their arrival,) all daubed over with broad arrows, P.B.s, C.B.s, and various numerals in black, white, and red".[39] In 1859, Caroline Leakey, writing under the pen-name "Oliné Keese", published a fictionalised account of the convict experience entitled The Broad Arrow: Being Passages from the History of Maida Gwynnham, a Lifer. In India The device was used in Colonial India, and continues to be used in modern India on military vehicle registration plates, although the symbol now employed is a standard typographical upward-pointing arrow rather than a true broad arrow.[40] In characterisation of internal combustion enginesMulti-cylinder internal combustion engines have their cylinder banks arranged in different ways. If there are just two, they may be in-line, opposed or at an angle, the latter often described as a Vee (or V) arrangement. When there are more than two cylinders, they are either arranged radially, in-line or in in-line groups. Thus a V-6 engine has two banks of three cylinders at an angle driving a common crankshaft, a V-12 two groups of six in-line. Broad arrow or W engines have three groups, one vertical and the two others symmetrically angled at less than 90° on either side. Both the air-cooled Anzani 3-cylinder fan engines of the "pioneer era" of aviation, and the later, "Golden Age of Aviation"-era British Napier Lion 12-cylinder, triple-bank liquid-cooled inline aviation engine could be said to have this layout when seen from a "nose-on" view. See alsoNotes

References

External links

|