|

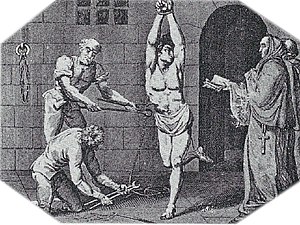

Black Legend of the Spanish InquisitionThe Black Legend of the Spanish Inquisition is the hypothesis of the existence of a series of myths and fabrications about the Spanish Inquisition used as propaganda against the Spanish Empire in a time of strong military, commercial and political rivalry between European powers, starting in the 16th century. According to its advocates, Protestant propaganda depicted inquisitions of Catholic monarchs as the epitome of human barbarity with fantastic scenes of tortures, witch hunting and evil friars. Proponents of the theory see it as part of the Spanish Black Legend propaganda, as well as of anti-Catholic propaganda, and one of the most recurrent black legend themes. Black legendAccording to the black legend theory, the factual reality of the Spanish Inquisition was distorted, turning it into a phenomenon of religious intolerance in which torture was practised. The theory supposes that it was mixed with fabrications and blown out of proportion: the argument is that the number of victims claimed would account for one third of the population and impact the economy in ways that were not observed; moreover, the advocates of the theory point to the fantastic descriptions of torture machines and stories of sadism and mutilation of millions of people, and claim they were fabricated in propaganda workshops.[1] Supporters of the theory argue that the context was ignored: both religious intolerance and torture were common practices all across Europe, and among the manifestations of it the Spanish inquisition proved itself, according to the theory, among the most mellow ones;[2][3] ignoring any positive traits (it was the first judicial body in Europe that operated according to a system and not to judicial discretion, torture was restricted to 15 minutes per session and only allowed on adults under very specific conditions for a set number of times,[4] inquisitors couldn't draw blood, mutilate or cause any permanent harm to victims[5] so waterboarding was the most common method as opposed to the fantastic devices portrayed in propaganda,[6] a doctor had to be present, (most inquisitors didn't believe in witchcraft[4] etc...); and finally systematically neglecting to mention similar actions by other institutions or nations). In Kamen's view this construction, the Black Legend, turns a relatively regular or unremarkable event into something exceptional in scope and nature, attached to one nation alone. As such, the Black Legend of the Inquisition is created to demonize the other - Spain and/or Catholicism - and maintained as self-justification for those whose own deeds are overshadowed or ignored. Origin Kamen[7] establishes two sources for the Black Legend of the Spanish Inquisition. Firstly, an Italian Catholic origin, and secondly, a Protestant background in Central and Northern Europe. Most historians place the bulk of the weight on the Protestant and Calvinist origin, since in the Italian propaganda Spaniards were more often portrayed as atheists or Jews than as fanatics.[8] ItalyThe increasing influence during the sixteenth century of the Aragonese Crown and later of the Spanish one on the Italian Peninsula led public opinion, and the Papacy, to see the Spaniards as a threat. An unfavorable image of Spain grew that ended up involving a negative view of the Inquisition. Revolts against the Inquisition in Spanish Crown territories in Sicily occurred in 1511 and 1526 and mere rumors of the future establishment of tribunals caused riots in Naples in 1547 and 1564. According to the theory of the Black Legend, ambassadors of the independent Italian governments promoted the image of an impoverished Spain dominated by a tyrannical Inquisition. In 1525, Venetian ambassador Contarini said that all people trembled before the Inquisition. Another ambassador, Tiepolo, wrote in 1563 that everyone was afraid of its authority, which had absolute power over property, life, honor and even the souls of men. He also commented that the King favored it as a way to control the population. Ambassador Soranzo asserted in 1565 that the Inquisition had greater authority than the King. Francesco Guicciardini, Florentine ambassador at the court of Charles I, stated that Spaniards were "in appearance religious, but not in reality", almost the same words by Tiepolo in 1536. In general, Italians considered the Inquisition as a necessary evil for the Spaniards, whose religion the Italians viewed as questionable if not false, after centuries of mixing with Jews and moriscos.[9] In fact, after 1492, the word marrano became synonymous with Spaniard and Pope Alexander VI was called the "circumcised marrano".[10] In contrast, Italians viewed placing an Inquisition in Italy as unnecessary, because they felt Spaniards were by nature more prone to heresy than pious Italians.[citation needed] In addition, the Papal Inquisition had been operating in Naples as a way of controlling the territory since the Middle Ages. One of the reasons why Spain wanted to introduce the Spanish Inquisition was precisely to counter or reduce that "foreign" influence in Spanish territory, and as such the Pope and powers rival to Spain encouraged disobedience to try and preserve their power in Naples.[11] However, Italian sources can hardly be considered as part of the construction legend, since their deformation of the facts is not systematic and sustained through time, but a temporary reaction to having a foreign institution imposed upon them; however, they may have been used out of context once the legend was established.[citation needed] Habsburg SpainThe Spanish Inquisition was one of the administrative and juridic arms of the Spanish Crown. It was created, among other things, to keep both powerful noble families and the Roman Catholic Church in check. This sectors of society had the power to dispute, or dodge, the authority of the king at a local level, and were also the demographics with higher literacy rates, wealth, and international relationships. The main role of the Inquisition was to prevent internal division in the empire and, even though the religious aspect of it is overly emphasized in the popular image, the fragmentation of power and local coalitions to dispute Royal power were an important part of this cohesion as well. It investigated nobles who wished to put their own local interests over the interests of the crown, and the Pope's desires to intervene and gain control over the Empire, usually with the aid of foreign powers (here is where the religious aspect comes and mixes since said powers usually were Protestant). As an independent body from the Pope, the Spanish Inquisition also had the ability to judge clergy for both corruption and treason without the interference of the Pope, which allowed the king to hold clergy accountable in his realm and limit Papal influence in it. As a consequence, the Inquisition systematically ruffled the feathers of the most powerful people inside the Spanish Empire as well as in the Vatican. The Spanish Inquisition's trial records show a disproportionate over-representation of nobility and clergy among those who are being investigated and prosecuted. The vast majority of the investigations that the Inquisition initiated itself (investigations on middle and low-class people were usually the consequence of denunciation by neighbors and rarely self-started by the institution). Among the trials, those who are conducted over nobility and clergy were also far more likely to be found guilty and convicted. While for the lay Spaniard who had no education to put their thoughts on paper nor the power to spread them, the Inquisition was far more compassionate and lenient than the civil alternative (the civil tribunals and the King's prisons, with no food and unrestricted use of torture), for the powerful the Inquisition was far worse than what they were used to in civil courts (no accountability at all). The sectors the Spanish Inquisition was designed to address and control were also the same sectors that had the education and resources to write and spread said writing, as well as the ones with something to win from any propaganda campaign. Either by accident, just as the result of mostly discontent people were the only ones who could write and talk about the institution internationally, or by design, the negative accounts from Spain's very international nobility constituted a large number of the total accounts of the Inquisition produced.[12] ProtestantismIn Northern Europe, the religious confrontation and the threat of Spanish imperial power gave birth to the Black Legend, as the small number of Protestants who were executed by the Inquisition would not have justified such a campaign. Protestants, who had successfully used the press to disseminate their ideas, tried to win with propaganda the war they could not win by force of arms.[13] On one hand, Catholic theologians criticized the Protestants as newcomers, who, unlike the Catholic Church could not prove a continuity from the time of Christ. On the other hand, Protestants theologians reasoned that this was not true and that theirs was the true Church which had been oppressed and persecuted by the Catholic Church throughout history.[13] This reasoning, which was only outlined by Luther and Calvin, was fleshed out by later Protestant historiography identified with Wycliffe of the Lollards, the Hussites of Bohemia and the Waldensians of France. All this despite the fact that in the 16th century heretics were persecuted in both Catholic and Protestant countries.[14][15] By the end of the 16th century the Protestant denominations had identified with the heretics of previous times and defined them as martyrs.[16] When the persecution of Protestants started in Spain the hostility felt towards the Pope was immediately extended to include the King of Spain, on whom the Inquisition depended, and the Dominicans who carried it out. After all, the greatest defeat suffered by the Protestants had been at the hands of Charles I of Spain in the battle of Mühlberg in 1547. An image of Spain as the champion of Catholicism spread throughout Europe. This image was in part promoted by the Spanish crown.  This identification by the Protestants with heretics from the time of the conversion of Imperial Rome until the 15th century lad to the creation of martyrologies in Protestant countries, description of the lives of martyrs in morbid detail, usually heavily illustrated, that circulated among the poorer classes and which incited indignation against the Catholic Church. One of the most famous and influential was the Book of Martyrs by John Foxe (1516–1587). Foxe dedicated an entire chapter to the Spanish Inquisition: The execrable Inquisition of Spayne.[17] Many of the themes that are repeated later on are to be found in this text: anyone can be tried for any triviality; the Inquisition is infallible; people are usually accused to gain money, because of jealousy, or to hide the actions of the Inquisition; if proof is not found it is invented; the prisoners are isolated with no contact with the outside world in dark dungeons where they suffer horrible torture etc. Foxe warned that this sinister organization could be introduced into any country that accepted the Catholic faith. Another influential book was the Sanctae Inquisitionis Hispanicae Artes (Exposition of the Arts of the Spanish Holy Inquisition) published in Heidelberg in 1567 under the pseudonym Reginaldus Gonsalvius Montanus. It appears that Gonzalvius was a pseudonym of Antonio del Corro, a Spanish Protestant theologian exiled in the United Provinces. Del Corro added credibility to his tale with his knowledge of the tribunal. The book was an immediate success, two editions were printed between 1568 and 1570 in English and French, three in Dutch, four in German and one in Hungarian, and the book continued to be published and referenced until the 19th century. The largely fabricated story relates the tale of a prisoner who passes through all the stages of the process and above all the interrogation, allowing the reader to identify with the victim. Del Corro's description presents some of the most extreme practices as being routine, such as the innocence of all the accused; the officials of the Inquisition are shown as being devious and vain and each step of the process is shown as a violation of natural law. Del Corro supported the initial purpose of the Inquisition, which was to persecute false converts, and he had not foreseen that his book would be used to support the Black Legend in a similar manner to that of Bartolomé de las Casas. He was convinced that the Dominican friars had converted the Inquisition into something execrable, that Philip II was not aware of the true proceedings and that the Spanish people were opposed to the sinister organization. Bourbon SpainSpanish Bourbons brought French absolutism and centralization to a largely decentralized and relatively liberal nation. The reaction was one of resentment and further polarization of Spanish society as the high nobility and the church, happy with the new acquisition of power, sided and supported the French monarchy ("afrancesados") while other sectors became polarised into growing antimonarchic and anti-French hostility. This situation contributed to feeding the black legend of the Inquisition from both extremes. On one side, the court of Spain was suddenly dominated by French intellectuals that came along with the first Bourbon king. As a result, the predominant historiographic view was the French view, which portrayed Spain and the Inquisition as violent and barbaric as consequence of centuries of rivalry between both powers. Those Spanish intellectuals who wished to advance and earn recognition in the court had to adopt said views in order to earn respect. On the other extreme, the protection for the absolutist Bourbons of the church generated a growing identification of the church, the old regime, monarchic absolutism and the king. Eventually, anti-monarchic intellectuals and Spaniards resenting the new rule started identifying the alleged cruelties of the medieval church and the Inquisition as reflections of their own perceived oppression under the Bourbons. The Black Legend of the Inquisition, already created and packed for consumption through the 16th and 17th century by anti-Catholic writers in Protestant countries, and introduced in Spain through France, was adopted by both sides. Since the legend used the alleged cruelty of the Inquisition to diminish both Spain and Catholicism, each side picked half of it and used it to either defend the "illustrated" French rule or to attack absolutism.[12] This strife provided a new body of completely misinformed and undocumented texts on the Inquisition written by Spaniards as propaganda against certain aspects of the government. During the 18th century, the existence of said Inquisition itself seemed to calm the waters and most criticisms were focussed towards the past. During the severe unrest of the 19th century, it was turned by the king not against foreign powers but against Spanish liberals.[18] Some examples of these Spanish Liberal contributions to the black legend are Goya's engravings, José del Olmo's narrative accounts, and engravings by Francisco Rizi (Italian but a Spanish sympathiser).[19] European politics in the 16th centuryA number of books appeared between 1559 and 1562 that presented the Inquisition as a threat to the liberties enjoyed by Europeans. These writings reasoned that those countries that accepted the Catholic religion not only lost their religious liberties but also their civil liberties due to the Inquisition. To illustrate their point they would describe autos-da-fé and tortures and they would provide numerous stories from people that had fled from the Inquisition. The Reformation was seen as a liberation of the human soul from darkness and superstition.[20] Dutch RepublicThere was a generally held fear in Holland dating from the reign of Charles I that the king would try to introduce the Inquisition in order to reduce civil liberties, even though Phillip II had stated that the Spanish Inquisition was not exportable. Phillip II recognized that Holland had its own inquisition more ruthless than the one in Spain. Between 1557 and 1562 the courts in Antwerp executed 103 heretics, more than were killed in the whole of Spain in this same period. Various changes in the organization of the Dutch Inquisition increased people's fears of both the Spanish Inquisition and the local one. In addition, opposition grew to such an extent through the 16th century that it was feared anarchy would break out if Calvinism was not legalized.  This fear was manipulated by Protestants and by those calling for Dutch independence in pamphlets such as On the Unchristian, tyrannical Inquisition that Persecutes Belief, Written from the Netherlands or The Form of the Spanish Inquisition Introduced in Lower Germany in the Year 1550 published by Michael Lotter. In 1570, religious refugees presented a document to the Imperial Diet entitled A Defence and true declaration of the things lately done in the lowe countrey which described not only the crimes perpetrated against Protestants but also accused the Spanish Inquisition of inciting revolts in Holland in order to force Phillip II to exercise a firm hand, and accused him of the death of Prince Carlos of Asturias. EnglandThe English fear of a Spanish invasion since the Spanish Armada during the Anglo-Spanish War stimulated anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic sentiment in England. John Story, an English MP and lawyer was kidnapped under orders from Elizabeth from the Dutch Republic where he was beheaded on charges of treason, which was influenced by allegations he still held onto his Catholic faith.[21][22][23] During this period, religious fanatics gained the support of others who were more moderate and above all of members of the government, which financed pamphlets and published edicts. During this time many pamphlets were published and translated including A Fig for the Spaniard.[24] A leaflet published by Antonio Pérez in 1598 entitled A treatise Paraenetical repeated William of Orange's claims conferring a tragic aspect to Prince Carlos of Asturias and one of religious fanaticism to Phillip II and the Inquisition that survived into modern era.[25] The 17th centuryDuring the 16th century some Catholic and Protestant thinkers had already begun to discuss the freedom of conscience, but the movement was marginal up until the start of the 17th century. It considered that those states that carried out religious persecution were not only poor Christians,[26] but also illogical,[27] given that they acted on the basis of a conjecture and not a certainty. These thinkers attacked all types of religious persecution, but the Inquisition offered them a perfect target for their criticism. These points of view were most popular with the followers of minority religious beliefs, "dissidents", such as Remonstrants, Anabaptists, Quakers, Unitarians, Mennonites etc. In fact, Philipp van Limborch, the great historian of the Inquisition, was a Remonstrant and Gilbert Brunet, an English historian of the Reformation was a Latitudinarian. Towards the end of the 16th century the religious wars in Europe had made it clear that any attempt to make religiously uniform states were bound to fail. Intellectuals, starting in Holland and France, affirmed that the State should occupy itself with the well-being of its citizens even if this allowed the growth of the heresy of allowing tolerance in exchange for social peace. By the end of the 17th century these ideas had spread to Central Europe and diversity was beginning to be considered more "natural" than uniformity, and that, in fact, uniformity threatened the richness of a nation. Spain was the perfect demonstration of this. It had started to decline economically by the middle of the 17th century and the expulsion of the Jews and other rich, industrious citizens was thought to be one of the main reasons for this decline. Also, the fines and seizures of property and wealth would make the problem worse, as the money was being directed to unproductive areas of the Catholic Church. The Inquisition was therefore converted into an enemy of the state and as such was reflected as such in the economic and political tracts of the time. In 1673, Francis Willoughby wrote A Relation of a Voyage Made through a Great Part of Spain in which he concluded the following:[28]

The liberal European societies started to look down on those societies that maintained their uniformity, they were also the object of social analysis. The existence of the Inquisition in Portugal, Spain and Rome was thought to be due to the use of force or because the spirit of the people was weakened, it was not considered possible that the Inquisition was supported voluntarily. This supposed weakness of spirit combined with the strength of the Inquisition in these countries was predicted to lead to a lack of imagination and learning as well as hindering advances in science, literature and the arts. Spain, despite the golden age of the Siglo de Oro and although the Inquisition generally only focused on doctrinal matters, is represented after the 17th century as a country without literature, art or science. As of the 17th century the "Spanish character" was included as part of the analysis of the Inquisition. This supposed "Spanish character" was publicized in many travel books which were the most popular type of literature of the period. One of the first and the most influential was written by the Countess d'Aulnoy in 1691 in which she consistently belittled Spanish achievements in the arts and sciences. Other notable books from the 18th century include those by Juan Álvarez de Colmenar, (1701), Jean de Vayarac (1718), Pierre-Louis-Auguste de Crusy, Marquis de Marcillac,[29] Edward Clarke,[30] Henry Swinburne,[31] Tobias George Smollett,[32] Richard Twiss and innumerable others who perpetuated the Black Legend.[33] It has been noted that influential Enlightenment writers such as Pierre Bayle (1647–1706) obtained much of their knowledge of Spain from these stories. The EnlightenmentMontesquieu saw in Spain the perfect example of the maladministration of a state under the influence of the clergy. Once again the Inquisition was deemed to be guilty of the economic ruin of nations, the great enemy of political freedom and social productivity, and not just in Spain and Portugal, there were signs throughout Europe that other countries could come to be "infected" with this contagion. He described an Inquisitor as someone "separated from society, in a wretched condition, starved of any kind of relationship, so that he will be tough, ruthless and inexorable...". In his book "The Spirit of the Laws" he dedicates chapter XXV.13 to the Inquisition. The chapter is written in such a way as to call attention to a young Jew who was burnt to death by the Inquisition in Lisbon. Montesquieu is therefore one of the first to describe the Jews as victims.  No 18th-century author did more to disparage religious persecution than Voltaire. Voltaire did not have a deep knowledge of the Inquisition until later in life, but he often used it to sharpen his satire and ridicule his opponents, as shown by his Don Jerónimo Bueno Caracúcarador, an Inquisitor who appears in Histoire de Jenni (1775). In Candide (1759), one of his best known titles, he does not show a knowledge of the functioning of the Inquisition greater than that to be found in travel books and general histories. Candide includes his famous description of an auto-da-fé in Lisbon, a satirical gem, that introduces the Inquisition to comedy. Voltaire's attacks on the Inquisition became more serious and acute from 1761. He shows a better understanding and knowledge of the internal workings of the tribunal, probably thanks to the work of Abbe Morellet who he used extensively and to his direct knowledge of some cases, such as that of Gabriel Malagrida, whose death in Lisbon caused a wave of indignation throughout Europe. Abbe Morellet published his Petite écrit sur une matière intéresante and Manuel des Inquisiteurs in 1762.[34] Both works extracted and summarized the darkest parts of the Inquisition and focussed on the use of deception to secure convictions, thereby making procedures known that even the most bitter enemies of the Inquisition had ignored. Abbe Guillaume-Thomas Raynal attained a fame equivalent to that of Montesquieu, Voltaire or Rousseau with his book Histoire philosophique et politique des établissements et du commerce des européens dans les deux Indes, even to the point that in 1789 he was considered one of the fathers of the French Revolution. His History of the Indies gained fame thanks to its censorship and a number of editions were published in Amsterdam, Geneva, Nantes and The Hague between 1770 and 1774. As one would expect, the book was also about the Inquisition. In this case Raynal did not criticize the deaths or the use of torture, instead he stated that thanks to the Inquisition Spain had not suffered religious wars. He thought that in order to return Spain to the Concert of Europe the Inquisition would need to be eliminated which would require the importation of foreigners of all beliefs as the only means of attaining "good results" in a reasonable amount of time; as he considered that the use of indigenous workers would take centuries to achieve the same results. One of the most important works of the century, L'Encyclopédie, dedicated one of its entries to the Inquisition. The article was written by Louis de Jaucourt a man of science who had studied at Cambridge and who also wrote the majority of the articles about Spain. Jaucourt was not very fond of Spain and many of his articles were filled with invective. He wrote articles on Spain, Iberia, Holland, wool, monasteries and titles of the nobility etc. which were all derogatory. Although his article on wine praised Spanish wine his conclusion was that its abuse can cause incurable illnesses. The article on the Inquisition is clearly taken from Voltaire's writings. For example, the description of the auto-da-fé is based on that given by Voltaire in Candide. The text is a ferocious attack against Spain:[35]

Repeating what Voltaire had already said: «The Inquisition would be the cause of the ignorance of philosophy that Spain lives in, thanks to which Europe and "even Italy" had discovered so many truths.» After the publication of L'Encyclopédie came an even more ambitious project, that of the "Encyclopédie méthodique" which comprised 206 volumes. The article on Spain was written by Masson de Morvilliers[36] and it naturally mentions the Inquisition. He advances the theory that the Spanish monarchy is nothing more than the play thing of the church and specifically the Inquisition. That is to say, the Inquisition is the true government of Spain. He explains that the cruelty of the Spanish Inquisition is due, in part, to the rivalry between the Franciscans and the Dominicans. In Venice and Tuscany the Inquisition was in the hands of the Franciscans and in Spain it was in the hands of the Dominicans. Who "in order to distinguish itself in this odious task, were led to unprecedented excesses". He recounts the legend of Philip III who on seeing the death of two convicts commented "Here are two unfortunate men who are dying for something they believe in!"[37] When the Inquisition was informed it demanded a phlebotomy of the King whose blood was then burnt. The 19th and 20th centuriesThe Historian Ronald Hilton[38] has attributed much importance to this 18th-century image of Spain. It would have given Napoleon the ideological justification for his invasion in 1807: the enlightened French taking their light to the backward and benighted Spain. In fact, one of the reforms that Napoleon introduced in Spain was the elimination of the Inquisition. In addition, Reverend Ingram Cobbin MA, in a 19th-century reissue of Foxe's The Book of Martyrs regaled his readers with the most fantastic tales about what the French troops found in the Inquisition's prison when they occupied Madrid[39]

United StatesIn the same way that Protestant Europe had used the Black Legend as a political weapon in the 16th century, the United States used it during the Cuban War of Independence. The American politician and orator Robert Green Ingersoll (1833–1899) is quoted as saying:[40]

In America in the 19th century, knowledge of the Inquisition was spread by Protestant polemical writers and historians such as Prescott and John Lothrop, whose ideology influenced the story. Along with the myths woven around the execution of witches in America the myth of the Inquisition was maintained as a malevolent abstraction, sustained by anti-Catholicism. According to Peters, the terms inquisition, inquisitorial and witch hunt became generalized in American society in the 1950s to refer to oppression by its government,[41] whether referring to the past or the present, this was possibly due to the influence of contemporary European authors. Carey McWilliams published Witch Hunt: The Revival of Heresy in 1950 which was a study of the Committee of Un-American Activities in which wide use was made of the term Inquisition to refer to the contemporary phenomenon of anticommunist hysteria. The tenor of the work was later widened in The American Inquisition, 1945–1960 by Cedric Belfrage and even later in 1982 with the book Inquisition: Justice and Injustice in the Cold War by Stanley Kutler. The term inquisition has become so widely used that it has come to be a synonym for "official investigation, especially of a political or religious nature, characterized by its lack of respect for individual rights, prejudice on the part of the judges and cruel punishments".[42] The Black Legend in SpainThe degree to which the Spanish people accepted the Inquisition is hard to evaluate.[43] Kamen tried to summarize the situation by saying that the Inquisition was considered as an evil necessary for maintaining order. It is not as if there were not any critics of the Tribunal, there were many as is evident from the Inquisition's own archives, but these critics are not considered relevant to the Black Legend. For example, in 1542 Alonso Ruiz de Virués, humanist and Archbishop, criticized its intolerance and those that used chains and the axe to change the disposition of the soul; Juan de Mariana, despite supporting the Inquisition, criticized forced conversions and the belief in purity of blood (limpieza de sangre). Public opinion slowly started to change after the 18th century thanks to contacts with the outside world, as a consequence the Black Legend began to appear in Spain. The religious and intellectual freedom in France was watched with interest and the initial victims of the Inquisition, conversos and moriscos, had disappeared. Enlightened intellectuals started to appear such as Pablo de Olavide and later Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes and Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, who blamed the Inquisition for the injust treatment of the conversos. In 1811 Moratín published Auto de fe celebrado en la ciudad de Logroño[44] (Auto de fe held in the city of Logroño) which related the history of a large trial against a number of witches that took place in Logroño, with satirical comments from the author. However, these liberal intellectuals, some of whom were members of the government, were not revolutionary and were preoccupied with the maintenance of the social order. The Inquisition ceased to function in practice in 1808, during the Spanish War of Independence as it was abolished by the occupying French government, although it remained as an institution until 1834. A school of liberal historians appeared in France and Spain at the start of the 19th century who were the first to talk about Spanish decline. They considered the Inquisition to be responsible for this economic and cultural decline and for all the other evils that afflicted the country. Other European historians took up the theme later on and this position can still be seen today. This school of thought stated that the expulsion of the Jews and the persecution of the conversos had led to the impoverishment and decline of Spain as well as the destruction of the middle class.[45] This type of author made Menéndez y Pelayo exclaim:

This school of thought along with the other elements of the Black Legend would form part of the Spanish anticlericalism of the end of the 19th century. This anticlericalism formed part of many other ideologies of the left wing, such as socialism, communism and anarchism. This is demonstrated by a statement made by the Socialist Member of Parliament Fernando Garrido in April 1869[46] that the Church had used the "Court of the Inquisition as an instrument for its own ends. The Church used the Inquisition to gag freedom of expression and impede the diffusion of the truth. It imposed a rigid despotism over three and a half centuries of Spanish history". MisunderstandingsSome common mistakes when reporting inquisitorial activity done by 20th century historians can't be considered fully part of the black legend, even though they are likely prompted by assumptions created by the black legend in historiography. They tend to stem from a lack of awareness of the modern-bureaucratic nature of the Spanish Inquisition in a time in which most trials were still left to the judge's personal discrection and will. This are the most common: Trial-execution ratioHigh volume of investigationsLike any bureaucratic system, the Inquisitorial tribunal had an obligation to consider and investigate every case that any citizen of Spain brought to them, regardless of social level of the accuser or the previous opinion of the tribunal about the veracity of the claim. As a consequence the number of raw cases that the inquisition had to handle and the number of processes it opened was astronomical, even if the actual conviction rate of the Inquisitorial tribunal was low, 6% on average. The raw numbers of trials usually include cases of witchcraft or false accusations that were quickly identified as neighbours' fabrications and dismissed by the system. For example, the Spanish Inquisition trialed 3687 people for witchcraft from 1560 to 1700, of whom only 101 were found guilty.[47] Other estimates of trial-conviction ratio for witchcraft are even lower.[citation needed] A common mistake in some inquisitorial historiography has been to report the number of trials as number of convictions, or even of executions.[48] Another mistake is to assume that the elevated number of trials indicated an active prosecution and search by the inquisitors instead of cases brought to them, or to assume a high ratio of conviction per trial instead of reading through the entire sentences. The mistake comes from the high trial-conviction ratio in cases of heresy observed in Northern Europe in the same period, where verdict was not based on a system but left to individual discretion.[49] Multiple chargesAnother factor that contributed to the high number of inquisitorial investigations was the low conviction ratio. Due to its reputation of relative impartiality during its first two centuries of existence, Spanish citizens preferred the inquisitorial tribunal to the secular courts and presented their cases to them whenever possible. Those held in secular prisons also did all they could to be transferred to Inquisitorial prisons, since prisoners of the inquisitions had rights while those of the king did not. As such, defendants accused of civil infractions would blaspheme or self accuse of false conversion to be transferred to the Inquisition courts, which eventually made the Inquisitors elevate a complaint to the king.[50] Another factor that helped inflate the number of trials the inquisition is reported to have conducted, especially regarding witchcraft and false conversions, were the groups of accusations that often were investigated together. Accusers tended to throw "witchcraft" or other vague accusations into the mix, along with legitimate claims. Those cases in which witchcraft was tried along with other, serious accusations, are sometime reported as "trials of witchcraft by the inquisition". For example, Eleno de Céspedes was accused of witchcraft during a trial and is often reported as "having been trialed for witchcraft by the inquisition", although the trial began on charges of sodomy, and the later additional charge of witchcraft was dismissed by the tribunal, which convicted de Céspedes only of bigamy.[51][52] Role of the InquisitorIn popular culture the Inquisitor is an all-powerful, evil and sadistic entity. Even serious researchers who didn't take the time to investigate the Spanish legal system as a whole tend to make the mistake of attributing him more power in the final verdict than he held. As it has been stated, the Inquisitorial court was a court regulated by a system, not by a person, much like how courts work in modern European democracies. The inquisition was merely a civil servant, a bureaucrat. As such the inquisitor had no power to introduce his own judgment in the trials, he had power only to apply the law. This had its problems, but was more beneficial than not. A popular example of this can be found in Alonso de Salazar Frías's intervention in the case of the Witches of Zurragamurdi, one of the few cases of witchcraft in Spain that ended in actual execution. During the trial, the Inquisitor Frías, who like most educated Spaniards did not believe in witchcraft, refused to condemn the witches despite their voluntary confessions-no torture was used. He declared that "These women think that they can turn into ravens, but they are just mentally ill!" and " There were no witches in Spain until the French started talking and writing about them". However, he didn't have the power to arbitrary declare them innocent. The case was taken to the General-Inquisitor in Madrid, who agreed with Frías in considering that the women were not witches, just mentally disturbed. However, and even though both men considered that the women were not guilty, they had to be convicted because the neighbors refused to drop the charges and the legal requisites for conviction of any crime-voluntary confession of it combined with unanimous and consistent testimony from a lot of eyes witnesses- had been met. The judges had no right to make an arbitrary decision over the written law.[53] This shows both the bureaucratic and modern nature of the Spanish Inquisition when compared to other European courts, and the limited power the inquisitors themselves held. See alsoReferences

BibliographyIf there is no indication to the contrary, the contents comes from Kamen and Peters, with the exception of The Enlightenment the majority of which was sourced from Hilton.

|