|

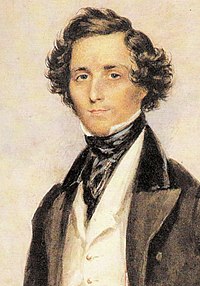

A Midsummer Night's Dream (Mendelssohn)

On two occasions, Felix Mendelssohn composed music for William Shakespeare's play A Midsummer Night's Dream (in German Ein Sommernachtstraum). First in 1826, near the start of his career, he wrote a concert overture (Op. 21). Later, in 1842, five years before his death, he wrote incidental music (Op. 61) for a production of the play, into which he incorporated the existing overture. The incidental music includes the famous "Wedding March". OvertureThe overture in E major, Op. 21, was written by Mendelssohn at 17 years and 6 months old (it was finished on 6 August 1826).[1] Contemporary music scholar George Grove called it "the greatest marvel of early maturity that the world has ever seen in music".[2] It was written as a concert overture, not associated with any performance of the play. The overture was written after Mendelssohn had read a German translation of the play in 1826. The translation was by August Wilhelm Schlegel, with help from Ludwig Tieck. There was a family connection as well: Schlegel's brother Friedrich married Felix Mendelssohn's Aunt Dorothea.[3] While a romantic piece in atmosphere, the overture incorporates many classical elements, being cast in sonata form and shaped by regular phrasings and harmonic transitions. The piece is also noted for its striking instrumental effects, such as the emulation of scampering 'fairy feet' at the beginning and the braying of Bottom as an ass (effects which were influenced by the aesthetic ideas and suggestions of Mendelssohn's friend at the time, Adolf Bernhard Marx). Heinrich Eduard Jacob, in his biography of the composer, surmised that Mendelssohn had scribbled the opening chords after hearing an evening breeze rustle the leaves in the garden of the family's home.[3] Also, Mendelssohn liberally used a theme borrowed from the Act II Finale of Carl Maria von Weber’s opera Oberon. Given that Mendelssohn’s overture has the same key and largely the same orchestration as that section of the opera, it was likely meant to be a tribute to the recently deceased Weber. The overture begins with four chords in the winds. Following the first theme in the parallel minor (E minor) representing the dancing fairies, a transition (the royal music of the court of Athens) leads to a second theme, that of the lovers. This is followed by the braying of Bottom with the "hee-hawing" being evoked by the strings. A final group of themes, reminiscent of craftsmen and hunting calls, brings the exposition to a close. The fairies dominate most of the development section, while the lover's theme is played in a minor key. The recapitulation begins with the same opening four chords in the winds, followed by the fairies theme and the other section in the second theme, including Bottom's braying. The fairies return, and ultimately have the final word in the coda, just as in Shakespeare's play. The overture ends once again with the same opening four chords by the winds. The overture was premiered in Stettin (then in Prussia; now Szczecin, Poland) on 20 February 1827,[4] at a concert conducted by Carl Loewe. Mendelssohn had turned 18 just over two weeks earlier. He had to travel 80 miles through a raging snowstorm to get to the concert,[5] which was his first public appearance. Loewe and Mendelssohn also appeared as soloists in Mendelssohn's Concerto in A-flat major for two pianos and orchestra, and Mendelssohn alone was the soloist for Carl Maria von Weber's Konzertstück in F minor. After the intermission, he joined the first violins for a performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.[6] The first British performance of the overture was conducted by Mendelssohn himself, on 24 June 1829, at the Argyll Rooms in London, at a concert in benefit of the victims of the floods in Silesia, and played by an orchestra that had been assembled by Mendelssohn's friend Sir George Smart.[4] At the same concert, Mendelssohn was the soloist in the English premiere of Beethoven's "Emperor" Concerto. After the concert, Thomas Attwood was given the score for the Overture for safe-keeping, but he left it in a cab and it was never recovered. Mendelssohn rewrote it from memory.[7] Incidental music Mendelssohn wrote the incidental music, Op. 61, for A Midsummer Night's Dream in 1842, 16 years after he wrote the overture. It was written to a commission from King Frederick William IV of Prussia. Mendelssohn was by then the music director of the King's Academy of the Arts and of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra.[8] A successful presentation of Sophocles' Antigone on 28 October 1841 at the New Palace in Potsdam, with music by Mendelssohn (Op. 55) led to the King asking him for more such music, to plays he especially enjoyed. A Midsummer Night's Dream was produced on 14 October 1843, also at Potsdam. The producer was Ludwig Tieck. This was followed by incidental music for Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus (Potsdam, 1 November 1845; published posthumously as Op. 93) and Jean Racine's Athalie (Berlin, 1 December 1845; Op. 74).[1] The A Midsummer Night's Dream overture, Op. 21, originally written as an independent piece 16 years earlier, was incorporated into the Op. 61 incidental music as its overture, and the first of its 14 numbers. There are also vocal sections and other purely instrumental movements, including the Scherzo, Nocturne and "Wedding March". The vocal numbers include the song "Ye spotted snakes" and the melodramas "Over hill, over dale", "The Spells", "What hempen homespuns", and "The Removal of the Spells". The melodramas served to enhance Shakespeare's text. Act 1 was played without music. The Scherzo, with its sprightly scoring, dominated by chattering winds and dancing strings, acts as an intermezzo between acts 1 and 2. The Scherzo leads directly into the first melodrama, a passage of text spoken over music. Oberon's arrival is accompanied by a fairy march, scored with triangle and cymbals. The vocal piece "Ye spotted snakes" ("Bunte Schlangen, zweigezüngt") opens act 2's second scene. The second intermezzo comes at the end of the second act. Act 3 includes a quaint march for the entrance of the Mechanicals. We soon hear music quoted from the overture to accompany the action. The Nocturne includes a solo horn doubled by bassoons, and accompanies the sleeping lovers between acts 3 and 4. There is only one melodrama in act 4. This closes with a reprise of the Nocturne to accompany the mortal lovers' sleep. The intermezzo between acts 4 and 5 is the famous "Wedding March", probably the most popular single piece of music composed by Mendelssohn, and one of the most ubiquitous pieces of music ever written. Act 5 contains more music than any other, to accompany the wedding feast. There is a brief fanfare for trumpets and timpani, a parody of a funeral march, and a Bergamask dance. The dance uses Bottom's braying from the overture as its main thematic material. The play has three brief epilogues. The first is introduced with a reprise of the theme of the "Wedding March" and the fairy music of the overture. After Puck's speech, the final musical number is heard – "Through this house give glimmering light" ("Bei des Feuers mattem Flimmern"), scored for solo soprano and women's chorus. Puck's famous valedictory speech "If we shadows have offended" is accompanied, as day breaks, by the four chords first heard at the very beginning of the overture, bringing the work full circle and to a fitting close. The music was dedicated to a gifted amateur musician friend of Mendelssohn's, Dr Heinrich Conrad Schleinitz.[9] MovementsIn published scores the overture and finale are usually not numbered.

Suite and excerptsThe purely instrumental movements (Overture, Scherzo, Intermezzo, Nocturne, "Wedding March", and Bergamask) are often played as a unified suite or as independent pieces, at concert performance or on recording, although this approach never had Mendelssohn's imprimatur. Like many others, Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra recorded selections for RCA Victor; Ormandy broke with tradition by using the German translation of Shakespeare's text. In the 1970s Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos recorded a Decca Records LP of the complete incidental music with the New Philharmonia Orchestra and soloists Hanneke van Bork and Alfreda Hodgson; it later was issued on CD.[10] In October 1992, Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra recorded another album of the full score for Deutsche Grammophon; they were joined by soloists Frederica von Stade and Kathleen Battle as well as the Tanglewood Festival Chorus. Actress Judi Dench was heard reciting those excerpts from the play that were acted against the music. In 1996, Claudio Abbado recorded an album for Sony Masterworks of extended excerpts with Kenneth Branagh acting several roles from the play, performed live.[11] ScoringThe overture is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, ophicleide, timpani and strings. The ophicleide part was originally written for English bass horn ("corno inglese di basso"), which was also used at the first performance and the London premiere in 1829;[6] the composer subsequently replaced this instrument with the ophicleide in the first published edition,[12] though Hogwood points out that it is unclear whether this was "an artistic or executive decision".[6] The incidental music adds a third trumpet, three trombones, triangle, cymbals, soprano, mezzo-soprano and women's chorus to this scoring. ArrangementsIn 1844 Mendelssohn arranged three movements for piano solo (Scherzo, Nocturne, Wedding March), which received their first recording by Roberto Prosseda in 2005. Slightly better known is the composer's own arrangement, also made in 1844, of five movements for piano duet (Overture, Scherzo, Intermezzo, Nocturne, Wedding March). Other arrangements for piano include: Franz Liszt's transcription of the Wedding March and Dance of the Elves, S410; Sigismond Thalberg's arrangement of the Scherzo; Moritz Moszkowski's arrangement of the Nocturne; and Sergei Rachmaninoff's arrangement of the Scherzo. There is a multitude of other arrangements for piano and for other instruments. UsesSections of the score were used in Woody Allen's 1982 film A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy.[13] Portions of the score were used extensively in the film The Scarlet Empress (1934), directed by Josef von Sternberg, starring Marlene Dietrich as Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia.[14][15] Director Max Reinhardt asked Erich Wolfgang Korngold to re-orchestrate Mendelssohn's Midsummer Night's Dream music for his 1935 film, A Midsummer Night's Dream.[16] Korngold added other works by Mendelssohn to the mix. Critic Leonard Maltin singles the music out for praise, as contemporary critics did.[16] The Scherzo is briefly used in the opening scene of the 2002 thriller Red Dragon.[17] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||