|

Toros Roslin

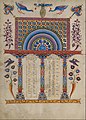

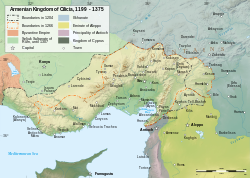

Toros Roslin (Armenian: Թորոս Ռոսլին, Armenian pronunciation: [tʰɔɹɔs rɔslin]); c. 1210–1270)[1] was the most prominent Armenian manuscript illuminator in the High Middle Ages.[2] Roslin introduced a wider range of narrative in his iconography based on his knowledge of western European art while continuing the conventions established by his predecessors.[2] Roslin enriched Armenian manuscript painting by introducing new artistic themes such as the Incredulity of Thomas and Passage of the Red Sea.[3] In addition he revived the genre of royal portraits, the first Cilician royal portraits having been found in his manuscripts.[4] His style is characterized by a delicacy of color, classical treatment of figures and their garments, an elegance of line, and an innovative iconography.[5] The human figures in his illustrations are rendered full of life, representing different emotional states. Roslin's illustrations often occupy the entire surface of the manuscript page and at times only parts of it, in other cases they are incorporated in the texts in harmony with the ensemble of the decoration.[6] Biography Little is known about Toros Roslin's life. He worked at the scriptorium of Hromkla in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia where the patriarchal see was transferred to in 1151.[2] His patrons included Catholicos Constantine I, king Hethum I, his wife Isabella, their children and prince Levon, in particular.[7] The colophons in Roslin's manuscripts permit scholars to partially reconstruct the world in which he lived in.[8] In these colophons Roslin appears as a chronicler, who preserved facts and events of his time. In his earliest surviving manuscript the Zeytun Gospel of 1256, Roslin signed his name as "Toros surnamed Roslin".[9] Only Armenians of noble origin had a surname in the Middle Ages; however, the surname of Roslin does not figure among the noble Armenian families.[10] Roslin may have been an offspring of one of the marriages common between Armenians and Franks (any person originating in Catholic western Europe) that were frequent among the nobility but occurred among the lower classes as well.[7] Roslin also names his brother Anton and asks the readers to recall the names of his teachers in their prayers.[7]  Levon Chookaszian proposed a more detailed explanation of the appearance of this surname in the Armenian milieu. He asserted that the surname Roslin originated from Henry Sinclair of the Clan Sinclair, baron of Roslin who accompanied Godfrey of Bouillon in the 1096 Crusade to Jerusalem. Chookaszian's hypothesis is based on the assumption that like most prominent Crusaders of the time,[11] Sinclair married an Armenian.[8] The approximate dates of Roslin's birth and death can be determined using the dates of his manuscripts. Based on the following it can be assumed that Roslin was at least 30 in 1260.[9] At the time one could only achieve the level of mastery displayed in the Zeytun Gospel of 1256 no earlier than in their mid twenties. In the colophon of the Gospel of 1260, Roslin mentions that he has a son, indicating that he was likely a priest since a monk would have no children while a member of the laity would likely not have been an illuminated manuscript painter. By the time of the Gospel of 1265, Roslin already had his own apprentices. Roslin painted two portraits of prince Levon, the earliest of which was executed in 1250[12] (the prince was born in 1236) and the second in 1262 showing the prince with his bride Keran of Lampron. Roslin's name isn't seen on any manuscript dated after 1286 and he most likely died in the 1270s.[13] None of Roslin's contemporaries or his pupils refer to him in their work and in the following centuries, his name is only mentioned once when the scribe Mikayel working in Sebastea in the late 17th century found in his monastery a gospel book illustrated in 1262 by the "famous scribe Roslin" which he later copied.[14] Manuscripts Signed by Toros RoslinSeven manuscripts have been preserved that bear the signature of Roslin, they are made between 1256 and 1268 five of which are copied and illustrated by Roslin.[15] Of these four are owned by the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem located in the Cathedral of St. James. These include the Gospel of 1260 (MS No. 251) copied for Catholicos Constantine I.[16] The Gospel of 1262 (MS No. 2660) was commissioned by Prince Levon, during the reign of King Het’um (I, 1226 to 1270),[17] copied at Sis by the scribe Avetis, illustrated by Roslin at Hromkla and bound by Arakel Hnazandents.[18] The Gospel of 1265 (MS No. 1965) was copied for the daughter of Constantine of Lampron, lady Keran who after the death of her husband Geoffrey, lord of Servandakar, retired from the world.[19] Mashtots (MS No. 2027) was commissioned in 1266 by bishop Vartan of Hromkla, copied by Avetis who had previously collaborated with Roslin in 1262 at Sis and illustrated by Roslin at Hromkla.[19] The Sebastia Gospel of 1262 (MS No. 539) is located in Baltimore's Walters Art Museum. It was copied for the priest Toros, nephew of Catholicos Constantine I. Written in uncials it is the most lavishly decorated among the signed works of Roslin.[16] The manuscript was kept in Sivas since the 17th century where it remained until the deportation of Armenians in 1919. Ten years later it was purchased by American rail magnate Henry Walters in Paris, whose long standing interest in Armenian art was rekindled by the tragic events of the previous decade. His wife Sadie Walters donated the manuscript to the Walters Art Museum in 1935.[20] The Zeytun Gospels of 1256 (MS. 10450), copied for Catholicos Constantine I {See link[21]}and the Malatia Gospel of 1268 (MS No. 10675) are located at the Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan. The manuscript (formerly MS No. 3627) was presented to Catholicos Vazgen I as a gift by Archbishop Yeghishe Derderian, patriarch of Jerusalem. The Catholicos in turn gave the manuscript to the institute. The manuscript was commissioned by Catholicos Constantine I as a present for the young prince and future king Hethum.[22] In the colophons of the manuscript Roslin describes the brutal sack of the Principality of Antioch by the Mamluk Sultan Baibars: "...at this time great Antioch was captured by the wicked king of Egypt, and many were killed and became his prisoners, and a cause of anguish to the holy and famous temples, houses of God, which are in it; the wonderful elegance of the beauty of those which were destroyed by fire is beyond the power of words."[23] Canon tables and ornamentsThe principal innovation of Roslin in regards to ornaments within canon tables is the addition of bust portraits.[24] In the Gospel of 1262 (MS No. 2660), Eusebius and Carpianus are represented as full figures standing in the outer margins of the Letter of Eusebius. Roslin also represented prophets such as David, Moses and John the Baptist.[25] This system was highly unusual for canon table decoration, for although portraits of prophets had been represented next to canon tables as early as the 6th-century Syriac Rabbula Gospels, their relationship to the gospels was not made explicit through the quotation of their messianic prophecies.[26] New zoomorphic creatures are also added to the usual repertoire of winged sphinxes and sirens such as dog or goat headed men carrying branches of flowers along with various quadrupeds and birds.[24] On the first page of each gospel and the beginning of pericopes floral as well as zoomorphic letters are formed utilizing peacocks or other creatures.[27] Attributions Several contemporary manuscripts from the 13th century, devoid of colophons have sometimes been attributed to Roslin.[7] MS 8321, the mutilated remains of which were formerly at Nor Nakhichevan and now in Yerevan, was commissioned by Catholicos Constantine I as a present for his godchild prince Levon. Prince Levon's portrait was bound by mistake in MS 7690 and was returned to its original place. A dedicatory inscription which faced the portrait has been lost. The portrait shows the prince in his teens wearing a blue tunic decorated with lions passant in gold roundels with a jeweled gold band at the hem. Two angels, in light blue and pink draperies, hold their rhipidia (liturgical fans) above the prince's head. Stylistically these pieces are much closer to the ones painted by Roslin than those of other artists at Hromkla who were still active in the 1250s.[28] Another mutilated manuscript, MS 5458 located in Yerevan is often assigned to Roslin. Thirty-eight vellum leaves from the Gospel of John have been incorporated into the manuscript in the late 14th or early 15th century in Vaspurakan. The priest Hovhannes who salvaged the remains of the old manuscript reports in one of the colophons that he had suffered seeing the old manuscript fall into the hands of the "infidels" like "a lamb delivered to wolves" and that he renovated it so that the "royal memorial written in it might not be lost". Part of the original colophons, the "royal memorial" reports that the manuscript was written in the see of Hromkla in 1266 for the king Hethum. The uncials are identical to that of MS 539 and similar marginal ornaments adorn both.[29] Yet another manuscript attributed to Roslin and his assistants is MS 32.18 currently located at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The colophons are lost but the name of the sponsor, Prince Vassak (brother of king Hethum I) is written on the marginal medallion on page 52: "Lord bless the baron Vassak" and again on the upper band of the frame around the Raising of Lazarus: "Lord have mercy on Vassak, Thy servant, the owner of this, Thy holy Gospel". The uncials and the ornaments match those of MS 539 and MS 5458.[30] Prince Vassak was sent to Cairo by his brother in 1268 to pay ransom and obtain the release of prince Levon and thousands of other hostages captured after the disastrous Battle of Mari. They returned home on June 24, 1268. At this time Roslin had already completed the copy and illustrations of MS 10675 and his chief patron, Catholicos Constantine I having died, Roslin would have been free to work for another patron such as prince Vassak who had a reason to celebrate.[31] IconographyAmong Roslin's various miniatures on the theme of the Nativity, the Nativity scene of the Gospel of 1260 (MS No. 251) stands out the most. Mary and the Child are presented seated on the throne near a grotto combined with in the lower angle with the portrait of Matthew the Evangelist, in reverse proportional correlation. The combination of the two scenes was originally developed in Constantinople during the Comnenian era and reinterpreted by Roslin.[32] Another unique attribute of this composition is seen in the top right corner where the bodyguards of the Magi, who are mentioned in apocryphal gospel accounts as soldiers who accompanied the Magi, are represented as Mongols. Art historian Sirarpie Der-Nersessian suggests that Roslin, "bearing in mind that the Magi came from the East, ...has represented the bodyguards with the facial type and costume of the Oriental peoples best known to him, namely the Mongols, the allies of king of Cilicia [Hethum I]."[33] LegacySirarpie Der-Nersessian devoted the longest chapter in her posthumously published magnum opus Miniature Painting in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia to Toros Roslin whose work she had researched for years. In the chapter she underlines: "Roslin's ability to convey deep emotion without undue emphasis," and in describing one of Roslin's scenes she extols: "The compositional design, the delicate modeling of the individual figures, and the subtle color harmonies show Roslin’s work at its best, equaling in artistic quality some of the finest Byzantine miniatures."[34] A 3.4 meter high statue of Toros Roslin made of basalt was erected in 1967 in front of the entrance of Matenadaran. The statue was designed by Mark Grigoryan and sculpted by Arsham Shahinyan.[35] A fine arts academy named after Toros Roslin was founded in 1981 by the Hamazkayin Armenian Educational and Cultural Association in Beirut, Lebanon.[36] See alsoGallery of his work

Notes

ReferencesWikimedia Commons has media related to Toros Roslin.

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||||