|

Theotokos

Theotokos (Greek: Θεοτόκος)[a] is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are Dei Genitrix or Deipara (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations are "Mother of God" or "God-bearer" – but these both have different literal equivalents in Ancient Greek: Μήτηρ Θεοῦ, and Θεοφόρος respectively.[4][5] The title has been in use since the 3rd century, in the Syriac tradition (as Classical Syriac: ܝܠܕܬ ܐܠܗܐ, romanized: Yāldath Alāhā/Yoldath Aloho) in the Liturgy of Mari and Addai (3rd century)[6] and the Liturgy of St James (4th century).[7] The Council of Ephesus in AD 431 decreed that Mary is the Theotokos because Her Son Jesus is both God and man: one divine person from two natures (divine and human) intimately and hypostatically united.[8][9] The title of Mother of God (Greek: Μήτηρ (τοῦ) Θεοῦ) or Mother of Incarnate God, abbreviated ΜΡ ΘΥ (the first and last letter of main two words in Greek), is most often used in English, largely due to the lack of a satisfactory equivalent of the Greek τόκος. For the same reason, the title is often left untranslated, as "Theotokos", in Eastern liturgical usage of other languages. Theotokos is also used as the term for an Eastern icon, or type of icon, of the Mother with Child (typically called a Madonna in western tradition), as in "the Theotokos of Vladimir" both for the original 12th-century icon and for icons that are copies or imitate its composition. Etymology

Theotokos is an adjectival compound of two Greek words Θεός "God" and τόκος "childbirth, parturition; offspring". A close paraphrase would be "[she] whose offspring is God" or "[she] who gave birth to one who was God".[10] The usual English translation is simply "Mother of God"; Latin uses Deipara or Dei Genitrix. The Church Slavonic translation is Bogoroditsa (Russian/Serbian/Bulgarian Богородица). The full title of Mary in Slavic Orthodox tradition is Прест҃а́ѧ влⷣчица на́ша бцⷣа и҆ прⷭ҇нод҃ва мр҃і́а (Russian Пресвятая Владычица наша Богородица и Приснодева Мария), from Greek Ὑπεραγία δέσποινα ἡμῶν Θεοτόκος καὶ ἀειπάρθενος Μαρία "Our Most Holy Lady Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary". German has the translation Gottesgebärerin (lit. "bearer of God"). In Arabic, there are two main terms which are widely used at the general level, first one is: "Walidatu-liilahi" (Arabic: وَالِدَةُ ٱلْإِلَـٰهِ, lit. 'Birther of God') and "Ùmmu-'llahi" or "Ùmmu-l'iilahi" (Arabic: أُمُّ ٱللهِ or أُمُّ ٱلْإِلَـٰهِ, lit.'Mother of God'). "Mother of God" is the literal translation of a distinct title in Greek, Μήτηρ τοῦ Θεοῦ (translit. Mētēr tou Theou), a term which has an established usage of its own in traditional Orthodox and Catholic theological writing, hymnography, and iconography.[11] In an abbreviated form, ΜΡ ΘΥ (М҃Р Ѳ҃Ѵ), it often is found on Eastern icons, where it is used to identify Mary. The Russian term is Матерь Божия (also Богома́терь).[12] Variant forms are the compounds

The theological dispute over the term concerned the term Θεός "God" vs. Χριστός "Christ", and not τόκος (genitrix, "bearer") vs. μήτηρ (mater, "mother"), and the two terms have been used as synonyms throughout Christian tradition. Both terms are known to have existed alongside one another since the early church, but it has been argued, even in modern times, that the term "Mother of God" is unduly suggestive of Godhead having its origin in Mary, imparting to Mary the role of a Mother Goddess. But this is an exact reiteration of the objection by Nestorius, resolved in the 5th century, to the effect that the term "Mother" expresses exactly the relation of Mary to the incarnate Son ascribed to Mary in Christian theology.[b][c][d][15] Theology

Theologically, the terms "Mother of God", "Mother of Incarnate God" (and its variants) should not be taken to imply that Mary is the source of the divine nature of Jesus, who Christians believe existed with the Father from all eternity.[16][17] Within the Orthodox and Catholic tradition, Mother of God has not been understood, nor been intended to be understood, as referring to Mary as Mother of God from eternity — that is, as Mother of God the Father — but only with reference to the birth of Jesus, that is, the Incarnation. To make it explicit, it is sometimes translated Mother of God Incarnate.[18] (cf. the topic of Christology, and the titles of God the Son and Son of man). The Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381 affirmed the Christian faith on "one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds (æons)", that "came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost and of the Virgin Mary, and was made man". Since that time, the expression "Mother of God" referred to the Dyophysite doctrine of the hypostatic union, about the uniqueness with the twofold nature of Jesus Christ God, which is both human and divine (nature distincted, but not separable nor mixed). Since that time, Jesus was affirmed as true Man and true God from all eternity.[citation needed] The status of Mary as Theotokos was a topic of theological dispute in the 4th and 5th centuries and was the subject of the decree of the Council of Ephesus of 431 to the effect that, in opposition to those who denied Mary the title Theotokos ("the one who gives birth to God") but called her Christotokos ("the one who gives birth to Christ"), Mary is Theotokos because her son Jesus is one person who is both God and man, divine and human.[8][9] This decree created the Nestorian Schism. Cyril of Alexandria wrote, "I am amazed that there are some who are entirely in doubt as to whether the holy Virgin should be called Theotokos or not. For if our Lord Jesus Christ is God, how is the holy Virgin who gave [Him] birth, not [Theotokos]?" (Epistle 1, to the monks of Egypt; PG 77:13B). But the argument of Nestorius was that divine and human natures of Christ were distinct, and while Mary is evidently the Christotokos (bearer of Christ), it could be misleading to describe her as the "bearer of God". At issue is the interpretation of the Incarnation, and the nature of the hypostatic union of Christ's human and divine natures between Christ's conception and birth. Within the Orthodox doctrinal teaching on the economy of salvation, Mary's identity, role, and status as Theotokos is acknowledged as indispensable. For this reason, it is formally defined as official dogma. The only other Mariological teaching so defined is that of her virginity. Both of these teachings have a bearing on the identity of Jesus Christ. By contrast, certain other Marian beliefs which do not bear directly on the doctrine concerning the person of Jesus (for example, her sinlessness, the circumstances surrounding her conception and birth, her Presentation in the Temple, her continuing virginity following the birth of Jesus, and her death), which are taught and believed by the Orthodox Church (being expressed in the Church's liturgy and patristic writings), are not formally defined by the Church.[citation needed] History of useEarly ChurchThe term was certainly in use by the 4th century. Athanasius of Alexandria in 330, Gregory the Theologian in 370, John Chrysostom[failed verification] in 400, and Augustine all used theotokos.[19] Origen (d. 254) is often cited as the earliest author to use theotokos for Mary (Socrates, Ecclesiastical History 7.32 (PG 67, 812 B) citing Origen's Commentary on Romans), but the surviving texts do not contain it. It is also claimed that the term was used c. 250 by Dionysius of Alexandria, in an epistle to Paul of Samosata,[20] but the epistle is a forgery of the 6th century.[21] The oldest preserved extant hymn dedicated to the Virgin Mary, Ὑπὸ τὴν σὴν εὐσπλαγχνίαν (English: "Beneath thy Compassion," Latin: Sub tuum praesidium,) has been continually prayed and sung for at least sixteen centuries, in the original Koine Greek vocative, as ΘΕΟΤΟΚΕ.[22] The oldest record of this hymn is a papyrus found in Egypt, mostly dated to after 450,[23] but according to a suggestion by de Villiers (2011) possibly older, dating to the mid-3rd century.[20] Third Ecumenical Council

The use of Theotokos was formally affirmed at the Third Ecumenical Council held at Ephesus in 431. It proclaimed that Mary truly became the Mother of God by the human conception of the Son of God in her womb:

The competing view, advocated by Patriarch Nestorius of Constantinople, was that Mary should be called Christotokos, meaning "Birth-giver of Christ," to restrict her role to the mother of Christ's humanity only and not his divine nature. Nestorius' opponents, led by Cyril of Alexandria, viewed this as dividing Jesus into two distinct persons, the human who was Son of Mary, and the divine who was not. To them, this was unacceptable since by destroying the perfect union of the divine and human natures in Christ, it sabotaged the fullness of the Incarnation and, by extension, the salvation of humanity. The council accepted Cyril's reasoning, affirmed the title Theotokos for Mary, and anathematized Nestorius' view as heresy. (See Nestorianism) In letters to Nestorius which were afterwards included among the council documents, Cyril explained his doctrine. He noted that "the holy fathers... have ventured to call the holy Virgin Theotokos, not as though the nature of the Word or his divinity received the beginning of their existence from the holy Virgin, but because from her was born his holy body, rationally endowed with a soul, with which the Word was united according to the hypostasis, and is said to have been begotten according to the flesh" (Cyril's second letter to Nestorius). Explaining his rejection of Nestorius' preferred title for Mary (Christotokos), Cyril wrote:

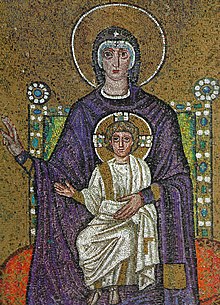

Nestorian schismThe Nestorian Church, known as the Church of the East within the Syrian tradition, rejected the decision of the Council of Ephesus and its confirmation at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. This was the church of the Sasanian Empire during the late 5th and early 6th centuries. The schism ended in 544, when patriarch Aba I ratified the decision of Chalcedon. After this, there was no longer technically any "Nestorian Church", i.e. a church following the doctrine of Nestorianism, although legends persisted that still further to the east such a church was still in existence (associated in particular with the figure of Prester John), and the label of "Nestorian" continued to be applied even though it was technically no longer correct. Modern research suggests that also the Church of the East in China did not teach a doctrine of two distinct natures of Christ."[25] ReformationLutheran tradition retained the title of "Mother of God" (German Mutter Gottes, Gottesmutter), a term already embraced by Martin Luther;[26] and officially confessed in the Formula of Concord (1577),[27] accepted by the Lutheran World Federation.[28] Whilst Calvin believed that Mary was theologically speaking rightly qualified as "the mother of God", he rejected common use of this as a title, saying, "I cannot think such language either right, or becoming, or suitable. ... To call the Virgin Mary the mother of God can only serve to confirm the ignorant in their superstitions."[29] 20th centuryIn 1994, Pope John Paul II and Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East Mar Dinkha IV signed an ecumenical declaration, mutually recognizing the legitimacy of the titles "Mother of God" and "Mother of Christ." The declaration reiterates the Christological formulations of the Council of Chalcedon as a theological expression of the faith shared by both Churches, at the same time respecting the preference of each Church in using these titles in their liturgical life and piety.[30] LiturgyTheotokos is often used in hymns to Mary in the Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Catholic and Oriental Orthodox churches. The most common is Axion Estin (It is truly meet), which is used in nearly every service. Other examples include Sub tuum praesidium, the Hail Mary in its Eastern form, and All creation rejoices, which replaces Axion Estin at the Divine Liturgy on the Sundays of Great Lent. Bogurodzica is a medieval Polish hymn, possibly composed by Adalbert of Prague (d. 997). The Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God is a Roman Catholic feast day introduced in 1969, based on older traditions associating 1 January with the motherhood of Mary.[e][31][f][32] IconographyOne of the two earliest known depictions of the Virgin Mary is found in the Catacomb of Priscilla (3rd century) showing the adoration of the Magi. Recent conservation work at the Catacombs of Priscilla revealed that what had been identified for decades as the earliest image of the Virgin and Child was actually a traditional funerary image of a Roman matron; the pointing figure with her, formerly identified as a prophet, was shown to have had its arm position adjusted and the star he was supposedly pointing to was painted in at a later date.[33] The putative Annunciation scene at Priscilla is also now recognized as yet another Roman matron with accompanying figure and not the Virgin Mary.[citation needed] Recently another third-century image of the Virgin Mary was identified at the eastern Syrian site of Dura Europos in the baptistry room of the earliest known Christian Church. The scene shows the Annunciation to the Virgin.[34] The tradition of Marian veneration was greatly expanded only with the affirmation of her status as Theotokos in 431. The mosaics in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, dating from 432 to 40, just after the council, does not yet show her with a halo. The iconographic tradition of the Theotokos or Madonna (Our Lady), showing the Virgin enthroned carrying the infant Christ, is established by the following century, as attested by a very small number of surviving icons, including one at Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai, and Salus Populi Romani, a 5th or 6th-century Byzantine icon preserved in Rome. This type of depiction, with subtly changing differences of emphasis, has remained the mainstay of depictions of Mary to the present day. The roughly half-dozen varied icons of the Virgin and Child in Rome from the 6th to 8th centuries form the majority of the representations surviving from this period, as most early Byzantine icons were destroyed in the Byzantine Iconoclasm of the 8th and 9th century,[35] notable exceptions being the 7th-century Blachernitissa and Agiosoritissa. The iconographic tradition is well developed by the early medieval period. The tradition of Luke the Evangelist being the first to have painted Mary is established by the 8th century.[36] An early icon of the Virgin as queen is in the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome, datable to 705-707 by the kneeling figure of Pope John VII, a notable promoter of the cult of the Virgin, to whom the infant Christ reaches his hand. The earliest surviving image in a Western illuminated manuscript of the Madonna and Child comes from the Book of Kells of about 800 (there is a similar carved image on the lid of St Cuthbert's coffin of 698). The oldest Russian icons were imports from Byzantium, beginning in the 11th century. Gallery

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External linksLook up Theotokos in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Theotokos.

|