|

Symphony No. 4 (Bruckner)

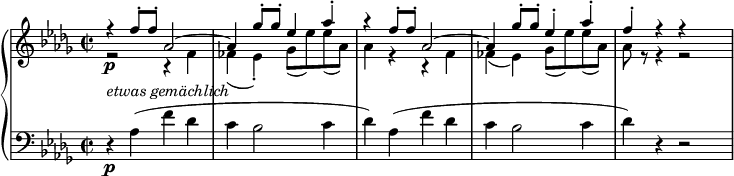

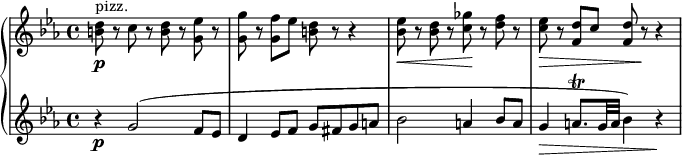

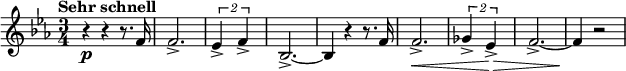

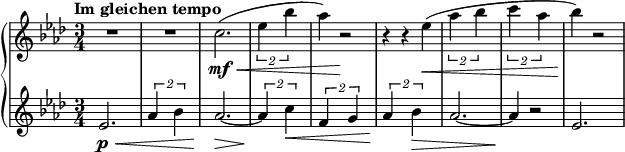

Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 4 in E-flat major, WAB 104, is one of the composer's most popular works. It was written in 1874 and revised several times through 1888. It was dedicated to Prince Konstantin of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst. It was premiered in 1881 by Hans Richter in Vienna to great acclaim. The symphony's nickname of Romantic was used by the composer himself. This was at the height of the Romantic movement in the arts as depicted, amongst others, in the operas Lohengrin and Siegfried of Richard Wagner.[1] According to Albert Speer, the symphony was performed before the fall of Berlin, in a concert on 12 April 1945. Speer chose the symphony as a signal that the Nazis were about to lose the war.[2] DescriptionThe symphony has four movements. Bruckner revised the symphony multiple times and it exists in three major versions. The initial version of 1874 differs in several respects from the other two, most importantly the entirely separate scherzo movement: Here are the tempo markings in the 1880 version: The 1888 version edited by Benjamin Korstvedtin the Gesamtausgabe (Band IV Teil 3) has different tempo and metronome markings: First movementThe movement opens, like many other Bruckner symphonies, with tremolo strings. A horn call opens the first theme group: This leads into the second theme of the first group, an insistent statement of the Bruckner rhythm: Like all Bruckner symphonies, the exposition contains three theme groups. The second group, called the "Gesangsperiode" by Bruckner, is in D♭ major: The third theme group differs between versions; in the 1874 original it opens with a variation on the opening horn call: In the 1878 version and later it opens with a variation of the Bruckner rhythm theme from the first group: The expansive development features a brass chorale based on the opening horn call: There exists much evidence that Bruckner had a program in mind for the Fourth Symphony. In a letter to conductor Hermann Levi of 8 December 1884, Bruckner wrote: "In the first movement after a full night's sleep the day is announced by the horn, 2nd movement song, 3rd movement hunting trio, musical entertainment of the hunters in the wood."[3] There is a similar passage in a letter from the composer to Paul Heyse of 22 December 1890: "In the first movement of the 'Romantic' Fourth Symphony the intention is to depict the horn that proclaims the day from the town hall! Then life goes on; in the Gesangsperiode [the second subject] the theme is the song of the great tit Zizipe. 2nd movement: song, prayer, serenade. 3rd: hunt and in the Trio how a barrel-organ plays during the midday meal in the forest.[3] In addition to these clues that come directly from Bruckner, the musicologist Theodor Helm communicated a more detailed account reported via the composer's associate Bernhard Deubler: "Mediaeval city—Daybreak—Morning calls sound from the city towers—the gates open—On proud horses the knights burst out into the open, the magic of nature envelops them—forest murmurs—bird song—and so the Romantic picture develops further..."[3] Second movementThis movement, in C minor, begins with a melody on the cellos: The accompaniment is significantly different in the original 1874 version. This movement, like most Bruckner slow movements, is in five-part ternary form (A–B–A–B–A–Coda). The second part (B) is slower than the first: Third movementBruckner completely recomposed the Scherzo movement after his first version. First version (1874)This so-called "Alphorn Scherzo" is based mostly on a horn call that opens the movement: This is followed by tremolo string figures and a slightly different version of the horn call. Eventually a climax is reached with the horn call sounded loudly and backed by the full orchestra, leading to the Trio: Second version (1878)The autograph of the so-called "Hunting Scherzo" of the 1878 version of the symphony contains markings such as Jagdthema (hunting theme) and Tanzweise während der Mahlzeit auf der Jagd (dance tune during the lunch break while hunting).[3] This is the more well known of the Scherzi. It opens with triadic hunting horn calls, that recalls the Military march, WAB 116:[4] The more melodic Trio follows: Fourth movementThis movement went through three major versions, but the third version of the Finale corresponds with the second major version of the symphony as a whole. There were further revisions for the 1888 version, but these amount to cuts and reorchestration; the underlying thematic material does not change after 1880. Much of the thematic material is shared between different versions, albeit with rhythmic simplification after 1874. The stark main theme, in E♭ minor, is the same in all three versions: First version (1874)This version begins with cascading string figures and a reappearance of the horn call that opened the symphony, albeit first appearing on the oboe. This builds to a climax and the main theme is stated by the full orchestra. Pizzicato strings introduce the second theme group, built on two themes. This group is very polyrhythmic, with heavy usage of quintuplets. The first theme: This group has several bars of five notes against eight, beginning in the second theme: The third theme group is started by a descending B♭ minor scale, which recalls Wotan's Spear leitmotif, given by the whole orchestra: Towards the end, the horn call that opened the symphony returns, heralding the bright E♭ major finish to the symphony. Second version 'Volksfest' (1878)The second version of the movement, whose nickname, meaning 'people's festival', comes from Bruckner's autograph,[3] is generally not played as part of the symphony as a whole. It is a simplified and shortened version of the finale. The movement's opening and first theme group are generally the same as the first version. The second group shows substantial differences in rhythm, with the difficult quintuplets replaced by simpler rhythmic patterns (Bruckner rhythm "2 + 3" or "3 + 2"). The actual notes, leaving aside transpositions and differences in accompaniment and articulation, are unchanged. The first theme: The second theme: The third theme group is again headed off by a descending scale, with the rhythm simplified: Significant changes are made to the coda, bringing it closer to the third version. Third version (1880)This version has the most substantial changes. The cascading string figures are changed, and the overall mood is much more somber than in previous versions. After the first theme group comes the modified second group. Here Bruckner has inserted a new theme that precedes the two themes seen in the previous versions:[5] Additionally, the third theme group has been recomposed: In the coda, a quiet chorale is introduced at bar 489, and, before the peroration (at bar 517), an ascending scale[6] – a quote of that before the third climax in part 5 of the Adagio of the Fifth Symphony.[7] In the 1888 version, the recapitulation begins with the second theme group, skipping over the first entirely.[6] There does not seem to be any clear hint of a program for this third version of the finale.[3] VersionsBruckner scholars recognise currently three versions of the Fourth Symphony:

At least seven authentic versions and revisions of the Fourth Symphony have been identified.

In an interview given to coincide with his performance of the work with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra at the 2024 BBC Proms, conductor Simon Rattle stated that he had found fourteen versions of the symphony.[9] Rattle also made a cut before the finale, and composed his own four-bar transition to replace it.[9] Version I (1874)Bruckner's original version of the symphony was composed between 2 January and 22 November 1874. The edition by Leopold Nowak in 1975, based on manuscript Mus.Hs.6082, includes some revisions from 1875 that Bruckner made in the autograph score. This version was never performed or published during the composer's lifetime, though the Scherzo was played in Linz on 12 December 1909. The first complete performance was given in Linz more than a century after its composition on 20 September 1975 by the Munich Philharmonic conducted by Kurt Wöss. The first commercial recording was made in September 1982 by the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Eliahu Inbal (CD 2564 61371-2). 1876 variantIn 1876 Bruckner made some additional, mainly metrical adjustments, that he introduced in a copy of the autograph score (manuscript Mus.Hs.6032), when he prepared the score for a planned performance – which ultimately fell through.[10] The 1876 variant, that has been premiered in November 2020 by Jakub Hrůša with the Bamberger Symphoniker, has been issued by Benjamin Korstvedt in 2021. Version IIA (1878)When he had completed the original version of the symphony, Bruckner turned to the composition of his Fifth Symphony. When he had completed that piece he resumed work on the Fourth. Between 18 January and 30 September 1878 he thoroughly revised the first two movements and replaced the original finale with a new movement entitled Volksfest ("Popular Festival"). In December 1878 Bruckner replaced the original Scherzo with a completely new movement, which is sometimes called the "Hunt" Scherzo (Jagd-Scherzo). In a letter to the music critic Wilhelm Tappert (October 1878), Bruckner said that the new Scherzo "represents the hunt, whereas the Trio is a dance melody which is played to the hunters during their repast". The original title of the Trio reads: Tanzweise während der Mahlzeit auf der Jagd ("Dance melody during the hunters' meal"). The Volksfest finale was published as an appendix to Robert Haas's edition of 1936, and in a separate edition by Leopold Nowak in 1981. The complete 1878 version of the symphony has been first issued by William Carragan in 2014 for a foreseen performance by Gerd Schaller. A critical edition of the 1878 version has been issued by Benjamin Korstvedt in 2022. In close contact with Korstvedt, MusicaNova Phoenix, Arizona, has performed a world premiere of the 1878 version of the Symphony on 1 May 2022.[11][12] Version IIB (1880)After the lapse of almost a year (during which he composed his String Quintet in F Major), Bruckner took up his Fourth Symphony once again. Between 19 November 1879 and 5 June 1880 he composed a new finale – the third, though it shares much of its thematic material with the first version[13] – and discarded the Volksfest finale. This was the version performed at the work's premiere on 20 February 1881, which was the first premiere of a Bruckner symphony not to be conducted by Bruckner himself. Some changes made after the first performance of the latter – numerous changes in orchestration, a replacement of a 4-bar passage with a 12-bar passage in the Finale, and a 20-bar cut in the Andante.[14] Most of these changes are described in Carragan's "Red Book".[15] Moreover, Bruckner reworked the passage that bridges the end of the development section of the Finale and the beginning of the reprise. Bars 351–430, i.e. the transition at the end of the development as well as the reprise of the first motif and the first part of the second motif, were removed and replaced by a few bars new transition. This abbreviated version was used for the first performance and Bruckner specifically requested that it was used when the Fourth was played for a second time.[16] The 1880 version is available in an edition by Robert Haas, which was published in 1936, based on Bruckner's manuscript in the Austrian National Library.[17] 1886 variantThe 1886 version is largely the same as the 1880 version but has a number of changes – notably in the last few bars of the Finale, in which the third and fourth horns play the main theme of the first movement[14] – made by Bruckner while preparing a score of the symphony for Anton Seidl, who took it with him to New York City. This version was published in an edition by Nowak in 1953, based on the original copyist's score, which was rediscovered in 1952 and is now in the collection of Columbia University. In the title of Nowak's publication, it was confusingly described as the "1878–1880 version". It was performed in New York by Seidl on 4 April 1888. Version III (1888)With the assistance of Ferdinand Löwe and probably also Franz and Joseph Schalk, Bruckner thoroughly revised the symphony in 1887–88 with a view to having it published. Although Löwe and the Schalks made some changes to the score, these are now thought to have been authorized by Bruckner. This version was first performed, to acclaim, by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Hans Richter in Vienna on 20 January 1888. The only surviving manuscript which records the compositional process of this version is the Stichvorlage, or engraver's copy of the score, which was prepared for the symphony's publisher Albert J. Gutmann of Vienna. The Stichvorlage was written down by three main copyists whose identities are unknown – but it is possible they were none other than Löwe and the two Schalks. One copyist copied out the 1st and 4th movements; the others each copied out one of the inner movements. Some tempi and expression marks were added in a fourth hand; these may have been inserted by Hans Richter during rehearsals, or even by Bruckner, who is known to have taken an interest in such matters. The Stichvorlage is now in an inaccessible private collection in Vienna; there is, however, a set of black-and-white photographs of the entire manuscript in the Wiener Stadtbibliothek (A-Wst M.H. 9098/c).[19] In February 1888, Bruckner made extensive revisions to all four movements after having heard the premiere of the 1887 version the previous month. These changes were entered in Bruckner's own hand into the Stichvorlage, which he then dated. The Stichvorlage was sent to the Viennese firm of Albert J. Gutmann sometime between 15 May and 20 June 1888. In September 1889 the score was published by Gutmann. This was the first edition of the symphony to be published in the composer's lifetime. In 1890 Gutmann issued a corrected text of this edition, which rectified a number of misprints. A critical edition has been issued in 2004 by Benjamin Korstvedt.[20] Mahler reorchestrationIn 1895 Gustav Mahler made an arrangement of the 1888 version which is heavily cut and reorchestrated. It is available in recordings by Gennady Rozhdestvensky and Anton Nanut. Details of the different versionsThe following table summarises the details of the different versions.

Bruckner's Fourth Symphony and the "Bruckner Problem"Any critical appraisal of Bruckner's Fourth Symphony must take into account the so-called Bruckner Problem – that is, the controversy surrounding the degrees of authenticity and authorial status of the different versions of his symphonies. Between 1890 and 1935 there was no such controversy as far as the Fourth was concerned: Gutmann's print of the symphony, the 1888 version, was unchallenged. British musicologist Donald Tovey's analysis of the symphony mentioned no other version, nor does the Swiss theorist Ernst Kurth. Gutmann's version was the one performed by the leading conductors of the day: Mahler,[21] Weingartner, Richter and Fischer. HaasIn 1936, Robert Haas, editor of the Gesamtausgabe (the critical edition of all of Bruckner's works), dismissed the version printed in 1889 as being without authenticity, saying that "the circumstances that accompanied its publication can no longer be verified"[17] and calling it "a murky source for the specialist".[17] In Haas's opinion the 1880 version was the Fassung letzter Hand (that is, the last version of the symphony to be transmitted in a manuscript in Bruckner's own hand). It later transpired that this assertion is not entirely true, but when Haas denied authorial status to the 1889 version he was unaware that the Stichvorlage from which that print was taken has extensive revisions in Bruckner's own hand, which Bruckner made in February 1888 after the premiere of the 1887 version of the symphony. To account for the fact that Bruckner had allowed the 1888 version to be printed, Haas created the now popular image of Bruckner as a composer with so little confidence in his own orchestral technique that he was easily persuaded to accept the revisions of others like Löwe and the Schalks. Haas's 1936 edition contained the entire symphony based on Bruckner's 1881 autograph and included the Volksfest finale in an appendix: he described this edition as the "original version" (Originalfassung). He planned a second volume containing the earlier 1874 version of the symphony, but this was never completed.[22] In 1940 Alfred Orel announced the rediscovery of the Stichvorlage from which the 1888 version had been printed. He noted that Bruckner had emended it himself and in 1948 declared it the true Fassung letzter Hand. Even Haas appears to have had second thoughts on the matter when he learned of the existence of the Stichvorlage. In 1944 he announced his intention to restore the 1888 version to the Bruckner Gesamtausgabe; but events overtook him. NowakWith the Anschluss of Austria to Hitler's Germany in 1938, the Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag Wien (MWV) and the Internationale Bruckner-Gesellschaft (IBG) in Vienna had been dissolved, and all efforts had been transferred to Leipzig. In 1945, late into a bomb attack on Leipzig, the publishing stock was destroyed. After the war, the IBG, the MWV, and Bruckner's documented output returned to Austria. In 1951 Leopold Nowak presented the first volume of the Neue Bruckner-Gesamtausgabe with a corrected reprint of Alfred Orel's edition of the Ninth Symphony. Nowak had already served in score-editing capacities before 1945, had worked on discovering new sources, and had corrected errors.[23] About the Fourth Symphony, Nowak was not immediately convinced that the 1888 version was authentic. He rejected the evidence of the Stichvorlage on the grounds that Bruckner had not signed it. He also repeated, and revised, arguments Haas had invoked to cast doubt on Bruckner's involvement in the preparation of the 1887 version. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century most commentators accepted Haas's and Nowak's arguments without taking the trouble to investigate the matter any further.[24] The rediscovery of the copyist's score of the 1886 version was the only significant change to the Gesamtausgabe during Nowak's long editorship (1951–1989). Nowak issued critical editions of the original 1874 version (1975), the 1886 version (1953) and the Volksfest finale of the 1878 version (1981), as well as a new edition of the 1881 version (1981). Gutmann's print of the 1888 version, however, remained beyond the pale as far as Nowak was concerned. Critical appreciation of the symphony took an interesting turn in 1954, when Eulenburg issued a new edition of the 1888 version by the German-born British musicologist Hans F. Redlich. According to Redlich, the publication of the revised version in 1889 did not mark the end of the Fourth Symphony's long process of composition and revision, as most commentators had assumed, for on 18 January 1890 Bruckner supposedly began to indite yet another version of the symphony:

Redlich buttressed this argument by questioning the authenticity of a number of emendations to the score which he considered alien to Bruckner's native style. Among these, the following may be noted: the introduction of piccolo and cymbals in bar 76 of the finale; the use of pp cymbals in bar 473 of the finale; and the use of muted horns in bar 147 of the finale, the aperto command for which is omitted in bar 155.[26] In 1969 Deryck Cooke repeated these arguments in his influential series of articles The Bruckner Problem Simplified, going so far as to claim that Bruckner "withheld his ultimate sanction by refusing to sign the copy sent to the printer".[27] Cooke, who referred to the 1888 version as the "completely spurious… Löwe/Schalk score", concluded that the existence of the alleged manuscript of 1890 to which Redlich had first drawn attention effectively annulled all revisions made after 1881. KorstvedtIn 1996, however, critical opinion of the Fourth Symphony was turned on its head by the American musicologist Benjamin Korstvedt, who demonstrated that the manuscript referred to by Redlich and Cooke does not in fact exist: "Were it true that Bruckner made such a copy, Cooke's claim would merit consideration. But Bruckner never did. Redlich and Cooke were misled by a photograph in Haas's biography of Bruckner. This photograph, which shows the first page of Bruckner's autograph score of the second version, is cropped in such a way that the date 18. Jänner 1878 – which is mentioned by Haas – seems to read 18 Jänner 1890".[28][29] Korstvedt has also refuted Haas's oft-repeated argument that Bruckner was a diffident composer who lacked faith in his own ability and was willing to make concessions that contravened his own artistic judgement. No evidence has been adduced in support of this assessment of the composer. On the contrary, there are first-hand accounts from Bruckner's own associates that it was impossible to persuade him to accept emendations against his own better judgement. It is Korstvedt's contention that while the preparation of the 1888 version was indeed a collaborative effort between Bruckner, Löwe, and probably also Franz and Joseph Schalk, this in no way undermines its authorial status; it still represents Bruckner's final thoughts on his Fourth Symphony and should be regarded as the true Endfassung or Fassung letzter Hand. There is no evidence that Bruckner "refused" to sign the Stichvorlage. He may have omitted to do so, but this is also true of other Bruckner manuscripts whose authenticity is not doubted. Furthermore, there is no real evidence that Bruckner was forced to accept revisions in order to get the work published, as Haas claimed. The only condition that Gutmann made prior to publication was that he be paid 1,000 fl. in advance to cover his costs. Once this money was delivered to him, he would have been quite happy, presumably, to print whatever version of the symphony Bruckner sent him. In 2004 Korstvedt issued the first modern edition of the 1888 version of the symphony for the Gesamtausgabe.[30] In 2019 Korstvedt issued a modern edition of the 1881 version,[18] in 2021 an edition of the 1876 variant of the first version, and in 2022 the 1878 version. Composition historyThe following table summarizes the Fourth Symphony's complicated history of composition (or Wirkungsgeschichte, to use the critical term preferred by Bruckner scholars). The principal sources for these data are Korstvedt 1996 and Redlich 1954. (B = Bruckner; FS = Fourth Symphony; mvt = movement.)

InstrumentationThe score calls for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. From the 1878 revision onwards, a single bass tuba is also incorporated into the instrumentation. The published score of 1889 introduces a part for third flute (doubling on the piccolo) and a pair of cymbals. RecordingsThe first commercial recording of part of the symphony was of the scherzo from the 1888 version, made by Clemens Krauss with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1929. The first commercial recording of the entire symphony was made by Karl Böhm with the Staatskapelle Dresden in 1936, in the Haas/1881 version. The versions most often recorded are the Haas and Nowak editions of the 1880 score (referred to as the 1881 and 1886 versions in the list above). Any modern recording that does not specify this can be safely assumed to be one of these versions, while early LPs and CD remasterings of old recordings are usually of Ferdinand Löwe's 1888 edition (for example, those by Wilhelm Furtwängler and Hans Knappertsbusch). The first recording of the original 1874 version was by Kurt Wöss with the Munich Philharmonic – a live performance on 20 September 1975. The first studio recording of the 1874 version was by Eliahu Inbal with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony. The first recording of the 1878 version was by Warren Cohen with the MusicaNova Orchestra – a live performance on 1 May 2022.[12] First version (1874–1876)Nowak edition (1975), based on the 1874 manuscript

Korstvedt edition (2021), based on the 1876 revision

Version 2A (1878)Korstvedt edition (2022)

"Volksfest" finale only

Andante and "Volksfest" finale

Version 2B (1881–1886)Haas edition (1936, rev. 1944), based on the 1881 manuscript

Nowak edition (1953), based on the 1886 manuscript

Korstvedt edition (2018), based on the 1881 manuscript

Cohrs edition (2021), based on the 1881 manuscript

Third version (1888)First edition (Gutmann, 1889)

Mahler reorchestration (1895)

Korstvedt critical edition (2004)

Published editions of the symphony

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![{ \new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff \relative e''' { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"piano" \key c \major \clef treble \time 2/2 \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \tempo 2 = 43

e4.. \mf ( g,16 ) g4 -! g4 -! | % 2

f8 [ ( g8 ]\noBeam \once \override TupletBracket #'stencil = ##f

\times 2/3 {

as8 g8 f8

}

g4 ) r4 | % 3

e'4.. ( g,16 ) g4 -! g4 -! | % 4

\once \override TupletBracket #'stencil = ##f

\times 2/3 {

f8 ( g8 f8

}

e8\noBeam [d8 ]c4 ) r4

}

\new Staff \relative g { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"piano" \key c \major \clef treble \time 2/2

g2 \mf e'4.. ( g,16 ) | % 2

f'8\noBeam [d8 ]( \once \override TupletBracket #'stencil = ##f

\times 2/3 {

b8 d8 f8 )

}

e4 r4 | % 3

g,2 e'4.. ( g,16 ) | % 4

f'8 \noBeam [d8 ] ( \once \override TupletBracket #'stencil = ##f

\times 2/3 {

b8 g8 b8 )

}

c4 r4 }

>> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/a/2aewo2t5oixs7ppbwu4ey1tev5bspy3/2aewo2t5.png)