|

Rani Padmini

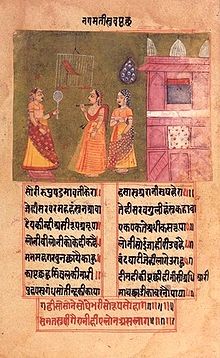

Padmini, also known as Padmavati, was a 13th–14th century Rani (queen) of the Mewar kingdom of present-day India. Several medieval texts mention her, although these versions are disparate and many modern historians question the extent of their overall authenticity.[2] The Jayasi text describes her story as follows: Padmavati was an exceptionally beautiful princess of the Sinhalese kingdom (in Sri Lanka).[a] Ratan Sen, the Rajput ruler of Chittor Fort, heard about her beauty from a talking parrot named Hiraman. After an adventurous quest, he won her hand in marriage and brought her to Chittor. Ratan Sen was captured and imprisoned by Alauddin Khalji, the Sultan of Delhi. While Ratan Sen was in prison, the king of Kumbhalner Devapal became enamoured with Padmavati's beauty and proposed to marry her. Ratan Sen returned to Chittor and entered into a duel with Devapal, in which both died. Alauddin Khalji laid siege to Chittor to obtain Padmavati. Facing a defeat against Khalji, before Chittor was captured, she and her companions committed Jauhar (self-immolation) thereby defeating Khalji's aim and protecting their honour. Coupled to the Jauhar, the Rajput men died fighting on the battlefield. Many other written and oral tradition versions of her life exist in Hindu and Jain traditions. These versions differ from the Sufi poet Jayasi's version. For example, Rani Padmini's husband Ratan Sen dies fighting the siege of Alauddin Khalji, and thereafter she leads a jauhar. In these versions, she is characterised as a Hindu Rajput queen, who defended her honour against a Muslim invader. Over the years she came to be seen as a historical figure and appeared in several novels, plays, television serials and movies. Versions of the legendSeveral 16th-century texts survive that offer varying accounts of Rani Padmini's life.[6] Of these, the earliest is the Awadhi language Padmavat (1540 CE) of the Sufi composer Malik Muhammad Jayasi, likely composed originally in the Persian script.[7] The 14th-century accounts written by Muslim court historians that describe Alauddin Khalji's 1302 CE conquest of Chittorgarh make no mention of this queen.[8] Jain texts between 14th and 16th century – Nabinandan Jenudhar, Chitai Charitra and Rayan Sehra have mentioned Rani Padmini.[5] Subsequently, many literary works mentioning her story were produced; these can be divided into four major categories:[9]

In addition to these various literary accounts, a variety of legends are located in vernacular oral traditions from about 1500 or later; these have evolved over time.[11][13] The oral legends and the literary accounts share the same characters and general plot, but diverge in the specifics and how they express the details. The oral versions narrate the social group's perspective while the early literary versions narrate the author's court-centric context.[13] According to Ramya Sreenivasan, the oral and written legends about Rani Padmini likely fed each other, each version of her life affected by the sensitivities of the audience or the patron, with Muslim versions narrating the conquest of Chitor by Delhi Sultanate under Alauddin Khalji, while the Hindu and Jain versions narrating the local resistance to the sultan of Delhi exemplified in the life of Padmini.[14] AccountsMalik Muhammad Jayasi's Padmavat (1540 CE)In the Jayasi version, states Ramya Sreenivasan, Padmavati is described as the daughter of Gandharvsen, the king of the island kingdom of Sinhala (Singhal kingdom, Sri Lanka).[15] A parrot tells Chittor's king Ratansen of Padmavati and her beauty. Ratansen is so moved by the parrot's description that he renounces his kingdom, becomes an ascetic, follows the parrot as the bird leads him across seven seas to the island kingdom.[16] There he meets Padmavati, overcomes obstacles and risks his life to win her. He succeeds, marries her and brings his wife to Chittor where he becomes king again. Ratansen expels a Brahmin scholar for misconduct, who then reaches Sultan Alauddin and tells him about the beautiful Padmavati.[16] The sultan lusts for Padmavati, and invades Chittor in his quest for her. Ratansen, meanwhile, dies in another battle with a rival Rajput ruler.[16] Padmavati immolates herself. Alauddin thus conquers Chitor for the Islamic state, but Alauddin fails in his personal quest.[17] This earliest known literary version is attributed to Jayasi, whose year of birth and death are unclear.[18] He lived during the rule of Babur, the Islamic emperor who started the Mughal Empire after ending the Delhi Sultanate. Jayasi's compositions spread in the Sufi tradition across the Indian subcontinent.[19] Variants derived from Jayasi's work on Padmavati were composed between the 16th and 19th centuries and these manuscripts exist in the Sufi tradition.[20] In one, princess Padmavati became close friends with a talking parrot named Hiraman. She and the parrot together studied the Vedas – the Hindu scriptures.[21] Her father resented the parrot's closeness to his daughter, and ordered the bird to be killed. The panicked parrot bade goodbye to the princess and flew away to save its life. It was trapped by a bird catcher, and sold to a Brahmin. The Brahmin bought it to Chittor, where the local king Ratan Sen purchased it, impressed by its ability to talk.[21] The parrot greatly praised Padmavati's beauty in front of Ratan Sen, who became determined to marry Padmavati. He leaves his kingdom as a Nath yogi. Guided by the parrot and accompanied by his 16,000 followers, Ratan Sen reached Singhal after crossing the seven seas. There, he commenced austerities in a temple to seek Padmavati. Meanwhile, Padmavati came to the temple, informed by the parrot, but quickly returned to her palace without meeting Ratan Sen. Once she reached the palace, she started longing for Ratan Sen.[21] Meanwhile, Ratan Sen realized that he had missed a chance to meet Padmavati. In desolation, he decided to immolate himself, but was interrupted by the deities Shiva and Parvati.[22] On Shiva's advice, Ratan Sen and his followers attacked the royal fortress of Singhal kingdom. They were defeated and imprisoned, while still dressed as ascetics. Just as Ratan Sen was about to be executed, his royal bard revealed to the captors that he was the king of Chittor. Gandharv Sen then married Padmavati to Ratan Sen, and also arranged 16,000 padmini women of Singhal for the 16,000 men accompanying Ratan Sen.[23]  Sometime later, Ratan Sen learned from a messenger bird that his first wife — Nagmati — is longing for him back in Chittor. Ratan Sen decided to return to Chittor, with his new wife Padmavati, his 16,000 followers and their 16,000 companions. During the journey, the Ocean God punished Ratan Sen for having excessive pride in winning over the world's most beautiful woman: everyone except Ratan Sen and Padmavati was killed in a storm. Padmavati was marooned on the island of Lacchmi, the daughter of the Ocean God. Ratan Sen was rescued by the Ocean God. Lacchmi decided to test Ratan Sen's love for Padmavati. She disguised herself as Padmavati, and appeared before Ratan Sen, but the king was not fooled. The Ocean god and Lacchmi then reunited Ratan Sen with Padmavati, and rewarded them with gifts. With these gifts, Ratan Sen arranged a new retinue at Puri, and returned to Chittor with Padmavati.[23] At Chittor, a rivalry developed between Ratan Sen's two wives, Nagmati and Padmavati. Sometime later, Ratan Sen banished a Brahmin courtier named Raghav Chetan for fraud. Raghav Chetan went to the court of Alauddin Khalji, the Sultan of Delhi, and told him about the exceptionally beautiful Padmavati.[23] Alauddin decided to obtain Padmavati, and besieged Chittor. Ratan Sen agreed to offer him tribute but refused to give away Padmavati. After failing to conquer to the Chittor fort, Alauddin feigned a peace treaty with Ratan Sen. He deceitfully captured Ratan Sen and took him to Delhi. Padmavati sought help from Ratan Sen's loyal feudatories Gora and Badal, who reached Delhi with their followers, disguised as Padmavati and her female companions. They rescued Ratan Sen; Gora was killed fighting the Delhi forces, while Ratan Sen and Badal reached Chittor safely.[24] Meanwhile, Devpal, the Rajput king of Chittor's neighbour Kumbhalner, had also become infatuated with Padmavati. While Ratan Sen was imprisoned in Delhi, he proposed marriage to Padmavati through an emissary. When Ratan Sen returned to Chittor, he decided to punish Devpal for this insult. In the ensuing single combat, Devpal and Ratan Sen killed each other. Meanwhile, Alauddin invaded Chittor once again, to obtain Padmavati. Facing a certain defeat against Alauddin, Nagmati and Padmavati along with other women of Chittor committed suicide by mass self-immolation (jauhar) in order to avoid being captured and to protect their honor. The men of Chittor fought to death against Alauddin, who acquired nothing but an empty fortress after his victory.[24] Khalji's imperial ambitions are defeated by Ratansen and Padmavati because they refused to submit and instead annihilated themselves.[25] Hemratan's Gora Badal Padmini Chaupai (1589 CE)Ratan Sen, the Rajput king of Chitrakot (Chittor) had a wife named Prabhavati, who was a great cook. One day, the king expressed dissatisfaction with the food she had prepared. Prabhavati challenged Ratan Sen to find a woman better than her. Ratan Sen angrily set out to find such a woman, accompanied by an attendant. A Nath Yogi ascetic told him that there were many padmini women on the Singhal island. Ratan Sen crossed the sea with help of another ascetic, and then defeated the king of Singhal in a game of chess. The king of Singhal married his sister Padmini to Ratan Sen, and also gave him a huge dowry which included half of the Singhal kingdom, 4000 horses, 2000 elephants and 2000 companions for Padmini.[26] In Chittor, while Ratan Sen and Padmini were making love, a Brahmin named Raghav Vyas accidentally interrupted them. Fearing Ratan Sen's anger, he escaped to Delhi, where he was received honourably at the court of Alauddin Khalji. When Alauddin learned about the existence of beautiful padmini women on the island of Singhal, he set out on an expedition to Singhal. However, his soldiers drowned in the sea. Alauddin managed to obtain a tribute from the king of Singhal, but could not obtain any padmini women. Alauddin learned that the only padmini woman on the mainland was Padmavati. So, he gathered an army of 2.7 million soldiers, and besieged Chittor. He deceitfully captured Ratan Sen, after having caught a glimpse of Padmini.[26] The frightened nobles of Chittor considered surrendering Padmini to Alauddin. But two brave warriors — Goru and Badil (also Gora and Vadil/Badal) — agreed to defend her and rescue their king. The Rajputs pretended to make arrangements to bring Padmavati to Alauddin's camp, but instead brought warriors concealed in palanquins. The Rajput warriors rescued the king; Gora died fighting Alauddin's army, as Badil escorted the king back to the Chittor fort. Gora's wife committed self-immolation (sati). In heaven, Gora was rewarded with half of Indra's throne.[27] James Tod's versionThe 19th-century British writer James Tod compiled a version of the legend in his Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han. Tod mentioned several manuscripts, inscriptions and persons as his sources for the information compiled in the book.[28] However, he does not name the exact sources that he used to compile the legend of Padmini in particular.[29] He does not mention Malik Muhammad Jayasi's Padmavat or any other Sufi adaptions of that work among his sources, and seems to have been unaware of these sources.[28] He does mention Khumman Raso in connection with the legend of Padmini, but he seems to have relied more on the local bardic legends along with Hindu and Jain literary accounts. Tod's version of Padmini's life story was a synthesis of multiple sources and a Jain monk named Gyanchandra assisted Tod in his research of the primary sources relating to Padmini.[30] According to Tod's version, Padmini was the daughter of Hamir Sank, the Chauhan ruler of Ceylon.[31] The contemporary ruler of Chittor was a minor named Lachhman Singh (alias Lakhamsi or Lakshmanasimha). Padmini was married to Lachhman Singh's uncle and regent Maharana Bhim Singh (alias Bhimsi).[32] She was famous for her beauty, and Alauddin (alias Ala) besieged Chittor to obtain her. After negotiations, Alauddin restricted his demand to merely seeing Padmini's beauty through a mirror and do so alone as a symbol of trust. The Rajputs reciprocate the trust and arrange to have Padmini sit in a room at the edge of a water tank. Alauddin gets a fleeting glimpse of her in a mirror in a building at a distance across the water tank. That glimpse inflamed his lust for her. The unsuspecting Rajput king further reciprocates the trust shown by Alauddin by accompanying the Sultan to his camp so that he returns without harm.[32] However, Alauddin had resolved to capture Padmini by treachery. The Sultan took Bhimsi hostage when they arrived at the Muslim army camp, and he demanded Padmini in return for Rajput king's release. Padmini plots an ambush with her uncle Gora and his nephew Badal, along with a jauhar – a mass immolation – with other Rajput women.[32] Gora and Badal attempt to rescue Bhimsi without surrendering Padmini. They informed Alauddin that Padmini would arrive accompanied by her maids and other female companions. In reality, soldiers of Chittor were placed in palanquins, and accompanied by other soldiers disguised as porters.[32] With this scheme, Gora and Badal managed to rescue Bhimsi, but a large number of the Chittor soldiers died in the mission. Alauddin then attacked Chittor once again with a larger force. Chittor faced a certain defeat. Padmini and other women died from self-immolation (jauhar). Bhimsi and other men then fought to death, and Alauddin captured the fort.[32][33] Inscriptions discovered after the publication of James Tod's version suggest that he incorrectly stated Lakshmanasimha (Lachhman Singh) as the ruler. According to these inscriptions, at the time of Alauddin's attack on Chittor, the local ruler was Ratnasimha (Ratan Singh or Ratan Sen), who is mentioned in other versions of the Rani Padmini-related literature.[34] Further, even though Lakshmanasimha's placement in 1303 was anachronistic, the evidence confirms that Lakshmanasimha resisted the Muslim invasion of Chittor after Ratnasimha.[35] Bengali adaptationsSyed Alaol composed the epic poem Padmavati in the mid-17th century which was influenced by Jayasi's text. According to this text, Padmini handed over the responsibility of her two sons to Alauddin before her death by committing jauhar.[36] Yagneshwar Bandyopadhyay's Mewar (1884) vividly describes the jauhar (mass self-immolation) of Padmini and other women, who want to protect their chastity against the "wicked Musalmans".[37] Rangalal Bandyopadhyay's patriotic and narrative poem Padmni Upakhyan based on the story of Rajput queen Padmini was published in 1858.[38][39] Kshirode Prasad Vidyavinode's play Padmini (1906) is based on James Tod's account: The ruler of Chittor is Lakshmansinha, while Padmini is the wife of the Rajput warrior Bhimsinha. Vidyavinode's story features several sub-plots, including those about Alauddin's exiled wife Nasiban and Lakshmansinha's son Arun. Nevertheless, his account of Alauddin and Padmini follows Tod's version with some variations. Alauddin captures Bhimsinha using deceit, but Padmini manages to rescue him using the palanquin trick; another noted warrior Gora is killed in this mission. As the Rajput men fight to death, Padmini and other women immolate themselves. The lineage of Lakshmansinha survives through Arun's son with a poor forest-dwelling woman named Rukma.[40] Abanindranath Tagore's Rajkahini (1909) is also based on Tod's narrative, and begins with a description of the Rajput history. Bhimsinha marries Padmini after a voyage to Sinhala, and brings her to Chittor. Alauddin learns about Padmini's beauty from a singing girl, and invades Chittor to obtain her. Bhimsinha offers to surrender his wife to Alauddin to protect Chittor, but his fellow Rajputs refuse the offer. They fight and defeat Alauddin. But later, Alauddin captures Bhimsinha, and demands Padmini in exchange for his release. Padmini, with support from the Rajput warriors Gora and Badal, rescues her husband using the palanquin trick; Gora dies during this mission. Meanwhile, Timur invades the Delhi Sultanate, and Alauddin is forced to return to Delhi. 13 years later, Alauddin returns to Chittor and besieges the fort. Lakshmansinha considers submission to Alauddin, but Bhimsinha convinces him to fight on for seven more days. With blessings of the god Shiva, Padmini appears before Lakshmansinha and his ministers as a goddess, and demands a blood sacrifice from them. The women of Chittor die in mass self-immolation, while the men fight to death. The victorious Alauddin razes all the buildings in Chittor, except Padmini's palace and then returns to Delhi.[41] Historicity    Alauddin Khalji's siege of Chittor in 1303 CE is a historical event. Although this conquest is often narrated through the legend of Padmini wherein Sultan Khalji lusted for the queen, this narration has little historical basis.[43] The earliest source to mention the Chittor siege of 1303 CE is Khaza'in ul-Futuh by Amir Khusrau, a court poet and panegyrist, who accompanied Alauddin during the campaign. Khusrau makes no mention of any Padmavati or Padmini, though later translator of Khusrau's allegorical work sees allusions to Padmini.[44] Amir Khusrau also describes the siege of Chittor in his later romantic composition Diwal Rani Khizr Khan (c. 1315 CE), which describes the love between a son of Alauddin and the princess of Gujarat. Again, he makes no mention of Padmini.[45] Some scholars, such as Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava, Dasharatha Sharma, and Mohammad Habib, have suggested that Amir Khusrau makes a veiled reference to Padmini in Khaza'in ul-Futuh.[46] Similarly, the historian Subimal Chandra Datta in 1931 stated that the Khusrau's 14th-century poetic eulogy of his patron's conquest of Chittor, there is a mention of a bird hudhud that in later accounts appears as a parrot,[47] and implies "Alauddin insisted on the surrender of a woman, possibly Padmini".[48]

Other historians, such as Kishori Saran Lal and Kalika Ranjan Qanungo, have questioned the interpretation that Amir Khusrau's reference is about Padmini.[49] According to Datta, a definitive historical interpretation of Khusrau's poetic work is not possible. It is unlikely that Alauddin attacked Chittor because of his lust for Padmini, states Datta, and his reasons were likely political conquest just like when he attacked other parts of Mewar region.[48] According to Ziauddin Barani, in 1297 CE, a Kotwal officer of Alauddin had told him that he would have to conquer Ranthambore, Chittor, Chanderi, Dhar and Ujjain before he could embark on world conquest. This, not Padmini, would have prompted Alauddin to launch a campaign against Chittor.[50] In addition, Mewar had given refuge to people who had rebelled or fought against Alauddin.[51] Datta states that there is a mention of Alauddin demanding Padmini during negotiations of surrender, a demand aimed to humiliate the long defiant Rajput state.[52] Further, Khusrau's account does abruptly mention that Alauddin went into the fort with him, but does not provide any details of why. The Khusrau source then mentions his patron emperor "crimson in rage", the Rajput king surrendering then receiving "royal mercy", followed by an order of Alauddin that led to "30,000 Hindus being slain in one day", states Datta.[53] The word Padmini or equivalent does not appear in the Khusrau source, but it confirms the siege of Chittor, a brutal war and the kernel of facts that form the framework of later era Padmini literature.[54] According to archeologist Rima Hooja, most of the romantic details of Jayasi's work are indeed legendary but the central plot of the text is certainly based on historical fact. Amir Khusrau's work presented Alauddin as Solomon and himself as Hud-Hud bird who carried the news of beautiful Queen of Shebha (who lives in Chittor fort) to Solomon. Further, being a courtier of Alauddin, Khusrau was not in a position to be straightforward about unpleasant facts of Alauddin's life and omitted several of those incidents from his work, including the murder of Jalal-ud-din Khalji for the throne and his defeat against the Mongols and their besieging of Delhi.[55] Development as a historical figureOther early accounts of the Chittor siege, such as those by Ziauddin Barani and Isami, do not mention Padmini. Their records state that Alauddin seized Chittor, set up military governors there, then returned to Delhi after forgiving Ratansen and his family.[56][57] The first uncontestable literary mention of Padmini is Malik Muhammad Jayasi's Padmavat (c. 1540 CE).[16] According to Ramya Sreenivasan, "it is possible that Jayasi mixed-up Alauddin Khilji and Ghiyath al-din Khilji of Malwa Sultanate (1469–1500) who had a roving eye, and is reported to have undertaken the quest for Padmini (not a particular Rajput princess, but the ideal type of woman according to Hindu erotology). Ghiyath al-din Khalji, according to a Hindu inscription in the Udaipur area, was defeated in battle in 1488 by a Rajput chieftain, Badal-Gora, which incidentally also happened to be the names of the twins, Badal and Gora, the vassals of Ratansen"[58] Hemratan's Gora Badal Padmini Chaupai (c. 1589 CE) narrates another version of the legend, presenting it as based on true events.[12] From then until the 19th century, several other adaptions of these two versions were produced.[11] The 16th-century historians Firishta and Haji-ud-Dabir were among the earliest writers to mention Padmini as a historical figure, but their accounts differ with each other and with that of Jayasi. For example, according to Firishta, Padmini was a daughter (not wife) of Ratan Sen.[59] Regarding the historicity of Padmini's story, historian S. Roy wrote in The History and Culture of the Indian People that "...... Abu-'l Fazl definitely says that he gives the story of Padminī from "ancient chronicles", which cannot obviously refer to the Padmāvat, an almost contemporary work. ...... it must be admitted that there is no inherent impossibility in the kernel of the story of Padminī devoid of all embellishments, and it should not be totally rejected off-hand as a myth. But it is impossible, at the present state of our knowledge, to regard it definitely as a historical fact."[60] When the British writer James Tod, who is now considered to be unreliable,[61] compiled the legends of Rajasthan in the 1820s, he presented Padmini as a historical figure, and Padmini came to be associated with the historical siege of Chittor. In the 19th century, during the Swadeshi movement, Padmini became a symbol of Indian patriotism. Indian nationalist writers portrayed her story as an example of a heroic sacrifice, and a number of plays featuring her were staged after 1905.[62] Ireland-born Sister Nivedita (1866–1971) also visited Chittor and historicised Padmini. The Rajkahini by Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951) popularised her as a historical figure among schoolchildren. Later, some history textbooks began to refer to Khalji invading Chittor to obtain Padmini.[63] Jawaharlal Nehru's The Discovery of India (1946) also narrates Khalji seeing Padmini in a mirror; Nehru's narrative is believed to be based on recent local poets.[citation needed] By the 20th century, Rajput Hindu women of Rajasthan characterised Padmini as a historical figure who exemplifies Rajput womanhood.[64] Hindu activists have characterised her as a chaste Hindu woman, and her suicide as a heroic act of resistance against the invader Khalji.[63] She has been admired for her character, her willingness to commit jauhar instead of being humiliated and accosted by Muslims, as a symbol of bravery and an exemplar like Meera.[65] Padmini Mahal (Padmini Palace), said to be the royal abode of Queen Padmini, is situated at the southern part of Chittorgarh Fort.[66][67][68] It is said that here Alauddin Khalji had a glimpse of Padmini's legendary beauty through a mirror.[69][3][70][71][b] Padmini's Palace find its mention in several historical texts of Mewar. his Palace find its reference in some of the historical texts of Mewar. One mention of it is in Amar Kavyam which states the confinement of Mahmud Khilji- II, Sultan of Malwa here by Rana Sanga. When Maharana Udai Singh married his daughter JasmaDe to Rai Singh of Bikaner, a song was composed about the charity done by Rai Singh, in which it is mentions that he donated an elephant for each step of the stairs of Padmini's Palace. It was repaired by Maharana Sajjan Singh, who got some new constructions done before Lord Ripon, the then Governor General of India, arrived here on 23 November 1881.[73] SymbolismThe life story of Rani Padmini appears in some Muslim Sufi, Hindu Nath and Jain tradition manuscripts with embedded notes that the legend is symbolic.[74] Some of these are dated to the 17th-century, and state that Chittor (Chit-aur) symbolizes the human body, the king is the human spirit, the island kingdom of Singhal is the human heart, Padmini is the human mind. The parrot is the guru (teacher) who guides, while Sultan Alauddin symbolizes the Maya (worldly illusion).[75] Such allegorical interpretations of the Rani Padmini's life story are also found in the bardic traditions of the Hindus and Jains in Rajasthan.[76] In popular cultureSeveral films based on the legend of Padmini have been made in India. These include Baburao Painter's Sati Padmini (1924), Debaki Bose's Kamonar Agun or Flames of Flesh (1930),[77] Daud Chand's Padmini (1948), and the Hindi language Maharani Padmini (1964).[78]

See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to Rani Padmini. Wikiquote has quotations related to Rani Padmini.

ReferencesNotes

Citations

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||