|

Mental model

A mental model is an internal representation of external reality: that is, a way of representing reality within one's mind. Such models are hypothesized to play a major role in cognition, reasoning and decision-making. The term for this concept was coined in 1943 by Kenneth Craik, who suggested that the mind constructs "small-scale models" of reality that it uses to anticipate events. Mental models can help shape behaviour, including approaches to solving problems and performing tasks. In psychology, the term mental models is sometimes used to refer to mental representations or mental simulation generally. The concepts of schema and conceptual models are cognitively adjacent. Elsewhere, it is used to refer to the "mental model" theory of reasoning developed by Philip Johnson-Laird and Ruth M. J. Byrne. HistoryThe term mental model is believed to have originated with Kenneth Craik in his 1943 book The Nature of Explanation.[1][2] Georges-Henri Luquet in Le dessin enfantin (Children's drawings), published in 1927 by Alcan, Paris, argued that children construct internal models, a view that influenced, among others, child psychologist Jean Piaget. Jay Wright Forrester defined general mental models thus:

Philip Johnson-Laird published Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference and Consciousness in 1983. In the same year, Dedre Gentner and Albert Stevens edited a collection of chapters in a book also titled Mental Models.[3] The first line of their book explains the idea further: "One function of this chapter is to belabor the obvious; people's views of the world, of themselves, of their own capabilities, and of the tasks that they are asked to perform, or topics they are asked to learn, depend heavily on the conceptualizations that they bring to the task." (see the book: Mental Models). Since then, there has been much discussion and use of the idea in human-computer interaction and usability by researchers including Donald Norman and Steve Krug (in his book Don't Make Me Think). Walter Kintsch and Teun A. van Dijk, using the term situation model (in their book Strategies of Discourse Comprehension, 1983), showed the relevance of mental models for the production and comprehension of discourse. Charlie Munger popularized the use of multi-disciplinary mental models for making business and investment decisions.[4] Mental models and reasoningOne view of human reasoning is that it depends on mental models. In this view, mental models can be constructed from perception, imagination, or the comprehension of discourse (Johnson-Laird, 1983). Such mental models are similar to architects' models or to physicists' diagrams in that their structure is analogous to the structure of the situation that they represent, unlike, say, the structure of logical forms used in formal rule theories of reasoning. In this respect, they are a little like pictures in the picture theory of language described by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in 1922. Philip Johnson-Laird and Ruth M.J. Byrne developed their mental model theory of reasoning which makes the assumption that reasoning depends, not on logical form, but on mental models (Johnson-Laird and Byrne, 1991). Principles of mental modelsMental models are based on a small set of fundamental assumptions (axioms), which distinguish them from other proposed representations in the psychology of reasoning (Byrne and Johnson-Laird, 2009). Each mental model represents a possibility. A mental model represents one possibility, capturing what is common to all the different ways in which the possibility may occur (Johnson-Laird and Byrne, 2002). Mental models are iconic, i.e., each part of a model corresponds to each part of what it represents (Johnson-Laird, 2006). Mental models are based on a principle of truth: they typically represent only those situations that are possible, and each model of a possibility represents only what is true in that possibility according to the proposition. However, mental models can represent what is false, temporarily assumed to be true, for example, in the case of counterfactual conditionals and counterfactual thinking (Byrne, 2005). Reasoning with mental modelsPeople infer that a conclusion is valid if it holds in all the possibilities. Procedures for reasoning with mental models rely on counter-examples to refute invalid inferences; they establish validity by ensuring that a conclusion holds over all the models of the premises. Reasoners focus on a subset of the possible models of multiple-model problems, often just a single model. The ease with which reasoners can make deductions is affected by many factors, including age and working memory (Barrouillet, et al., 2000). They reject a conclusion if they find a counterexample, i.e., a possibility in which the premises hold, but the conclusion does not (Schroyens, et al. 2003; Verschueren, et al., 2005). CriticismsScientific debate continues about whether human reasoning is based on mental models, versus formal rules of inference (e.g., O'Brien, 2009), domain-specific rules of inference (e.g., Cheng & Holyoak, 2008; Cosmides, 2005), or probabilities (e.g., Oaksford and Chater, 2007). Many empirical comparisons of the different theories have been carried out (e.g., Oberauer, 2006). Mental models of dynamics systems: mental models in system dynamicsCharacteristicsA mental model is generally:

Mental models are a fundamental way to understand organizational learning. Mental models, in popular science parlance, have been described as "deeply held images of thinking and acting".[8] Mental models are so basic to understanding the world that people are hardly conscious of them. Expression of mental models of dynamic systemsS.N. Groesser and M. Schaffernicht (2012) describe three basic methods which are typically used:

These methods allow showing a mental model of a dynamic system, as an explicit, written model about a certain system based on internal beliefs. Analyzing these graphical representations has been an increasing area of research across many social science fields.[9] Additionally software tools that attempt to capture and analyze the structural and functional properties of individual mental models such as Mental Modeler, "a participatory modeling tool based in fuzzy-logic cognitive mapping",[10] have recently been developed and used to collect/compare/combine mental model representations collected from individuals for use in social science research, collaborative decision-making, and natural resource planning. Mental model in relation to system dynamics and systemic thinkingIn the simplification of reality, creating a model can find a sense of reality, seeking to overcome systemic thinking and system dynamics. These two disciplines can help to construct a better coordination with the reality of mental models and simulate it accurately. They increase the probability that the consequences of how to decide and act in accordance with how to plan.[5]

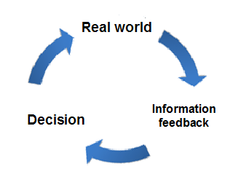

Experimental studies carried out in weightlessness[11] and on Earth using neuroimaging [12] showed that humans are endowed with a mental model of the effects of gravity on object motion. Single and double-loop learningAfter analyzing the basic characteristics, it is necessary to bring the process of changing the mental models, or the process of learning. Learning is a back-loop process, and feedback loops can be illustrated as: single-loop learning or double-loop learning. Single-loop learningMental models affect the way that people work with information, and also how they determine the final decision. The decision itself changes, but the mental models remain the same. It is the predominant method of learning, because it is very convenient. Double-loop learningDouble-loop learning (see diagram below) is used when it is necessary to change the mental model on which a decision depends. Unlike single loops, this model includes a shift in understanding, from simple and static to broader and more dynamic, such as taking into account the changes in the surroundings and the need for expression changes in mental models.[6]

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External links |

|||||||||||||||