|

Kanuri language

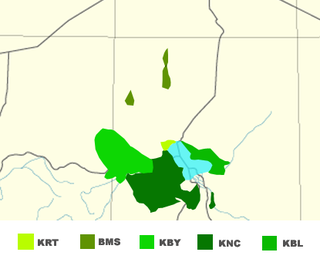

Kanuri (/kəˈnʊəri/[4]) is a Saharan dialect continuum of the Nilo–Saharan language family spoken by the Kanuri and Kanembu peoples in Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroon, as well as by a diaspora community residing in Sudan. BackgroundAt the turn of the 21st century, its two main dialects, Manga Kanuri and Yerwa Kanuri (also called Beriberi, which its speakers consider to be pejorative), were spoken by 9,700,000 people in Central Africa.[5] It belongs to the Western Saharan subphylum of Nilo-Saharan. Kanuri is the language associated with the Kanem and Bornu empires that dominated the Lake Chad region for a thousand years. The basic word order of Kanuri sentences is subject–object–verb. It is typologically unusual in simultaneously having postpositions and post-nominal modifiers – for example, 'Bintu's pot' would be expressed as nje Bintu-be, 'pot Bintu-of'.[6] Kanuri has three tones: high, low, and falling. It has an extensive system of consonantal lenition; for example, sa- 'they' + -buma 'have eaten' → za-wuna 'they have eaten'.[7] Traditionally a local lingua franca, its usage has declined in recent decades. Most first-language speakers speak Hausa or Arabic as a second language.[citation needed] Geographic distributionKanuri is spoken mainly in lowlands of the Chad Basin, with speakers in Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Sudan and Libya.[8] By countryNigeriaThe Kanuri region in Nigeria consists of Borno State and Yobe State. Some other states such as Jigawa, Gombe and Bauchi are also dominated by Kanuri people, but they are not included in this region. Cities and towns where Kanuri is spoken include Maiduguri, Damaturu, Hadejia, Akko, Duku, Kwami, Kano, Kaduna, Gusau, Jos and Lafia.[citation needed] In central Nigeria, the Kanuri are usually referred to as Bare-Bari or Beriberi.[citation needed] Central Kanuri, also known as Yerwa Kanuri, is the main language of the Kanuri people living in Borno State, Yobe State and Gombe State, and it is usually referred to as Kanuri in Nigeria.[citation needed] Manga Kanuri, which is the main language of the Kanuri people in Yobe State, Jigawa State and Bauchi State, is usually referred to as Manga or Mangari or Mangawa, and they are distinct from the Kanuri, which is a term generally used for speakers of Central Kanuri.[citation needed] The Kanembu language is also spoken in Borno State on the border with Chad.[citation needed] NigerIn Niger, the Kanuri region is composed of Diffa Region and Zinder Region in the southeast. Parts of Agadez Region are also Kanuri. Cities where it is spoken include Zinder, Diffa, N'Guigmi and Bilma.[citation needed] In Zinder region, the main dialect is Manga. In Diffa Region, the main dialect is Tumari or Kanembu; Kanembu is spoken by a minority. In Agadez Region, the main dialect is Bilma. Central Kanuri is a minority dialect, and is commonly referred to as Bare-Bari or Beriberi.[citation needed] VarietiesEthnologue divides Kanuri into the following languages, while many linguists (e.g. Cyffer 1998) regard them as dialects of a single language. The first three are spoken by ethnic Kanuri and thought by them as dialects of their language.

The variety attested in 17th-century Qur'anic glosses is known as Old Kanembu. In the context of religious recitation and commentaries, a heavily archaizing descendant of this is still used, called Tarjumo. PhonologyConsonants

Vowels

Written KanuriKanuri has been written using the Ajami Arabic script, mainly in religious or court contexts, for at least four hundred years.[11] More recently, it is also sometimes written in a modified Latin script. The Gospel of John published in 1965 was produced in Roman and Arabic script. AlphabetA standardized romanized orthography (known as the Standard Kanuri Orthography in Nigeria) was developed by the Kanuri Research Unit and the Kanuri Language Board. Its elaboration, based on the dialect of Maiduguri, was carried out by the Orthography Committee of the Kanuri Language Board, under the Chairmanship of Abba Sadiq, Waziri of Borno. It was officially approved by the Kanuri Language Board in Maiduguri, Nigeria, in 1975.[12] Letters used : a b c d e ǝ f g h i j k l m n ny o p r ɍ s sh t u w y z.[13]

Oral literatureIn 1854, Sigismund Koelle published African Native Literature, or Proverbs, Tales, Fables, and Historical Fragments in the Kanuri or Bornu Language[15] which contains texts in Kanuri and in English translation. There is a selection of proverbs,[16] stories and fables,[17] and historical fragments.[18] In his English translation, Koelle misidentifies the trickster ground-squirrel, kə̀nyérì, as a weasel. Richard Francis Burton in his Wit and Wisdom from West Africa included a selection of the proverbs reported by Koelle.[19] Here are some of those proverbs:

Sample text in Kanuri (Universal Declaration of Human Rights)Hakkiwa-a nambe a suro Wowur abəden dəganadə ndu-a nduana-aso kartaa, gayirtə futubibema baaro, gayirta alama jiilibeso, kadigəbeso, alagəbeso, təlambeso, adinbeso, siyasabeso au rayiwu, lardə gade au kaduwu gade, kənganti, tambo au awowa laa gade anyiga samunzəna. Anyibe ngawoman nduma kəla siyasaben, kal kəntəwoben kal au daraja dunyalabe sawawuro kal kərye au lardə kamdə dəganabe sawawuro gayirtinba. Lardə shi gultənama adə kərmai kəlanzəben karga, amanaro musko lardə gadeben karga, kəlanzəlangənyi karga au sədiya kaidawa kəntəwobe laan karga yaye kal. Translation Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under and other limitation of sovereingty. (Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights). See also

Sources

References

Sources

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||