|

Claiborne County, Mississippi

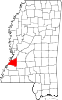

Claiborne County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2020 census, the population was 9,135.[1] Its county seat is Port Gibson.[2] The county is named after William Claiborne, the second governor of the Mississippi Territory. Claiborne County is included in the Vicksburg, MS Micropolitan Statistical Area as well as the Jackson-Vicksburg-Brookhaven, MS Combined Statistical Area. It is bordered by the Mississippi River on the west and the Big Black River on the north. As of the 2020 Census, this small county has the highest percentage of black or African American residents of any U.S. county, at 88.6% of the population.[3] Located just south of the area known as the Mississippi Delta, this area also was a center of cotton plantations and related agriculture along the river, supported by enslaved African Americans. After emancipation, many generations of African Americans have stayed here because of family ties and having made the land their own. Claiborne County was the center of a little-known but profound demonstration and struggle during the civil rights movement.[4] HistoryThe county had been settled by French, Spanish, and English colonists, and American pioneers as part of the Natchez District; organized in 1802, it was the fourth county in the Mississippi Territory.[5] European-American settlers did not develop the area for cotton plantations until after Indian Removal in the 1830s, at which time they brought in numerous slaves through the domestic slave trade. In total, this transported one million enslaved African Americans from the Upper South to the Deep South, disrupting numerous families. Using the enslaved workers, planters developed long plantations that had narrow fronts on the rivers: the Mississippi to the west and the Big Black River to the north,[5] which were the transportation byways. As in other parts of the Delta, the bottomlands areas further from the river remained largely frontier and undeveloped until after the American Civil War.[6] Well before the Civil War, the county had a majority-black population. Grand Gulf, a port on the Mississippi River, shipped thousands of bales of cotton annually before the Civil War. It received cotton shipped by railroad from Port Gibson and three surrounding counties. The trading town became cut off from the river by its changing course and shifting to the west. Grand Gulf had 1,000 to 1500 residents about 1858; by the end of the century, it had 150 and became a ghost town.[7] Businesses in the county seat of Port Gibson, which served the area, included a cotton gin and a cottonseed oil mill (which continued into the 20th century.) It has also been a retail center of trade. After the Reconstruction era, white Democrats regained power in the state legislature by the mid-1870s; paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts suppressed black voting through violence and fraud in many parts of the state.[8] These groups acted as "the military arm of the Democratic Party."[9]  In the late nineteenth century, these Redeemers redefined districts to "reduce Republican voting strength," creating a "'shoestring' Congressional district running the length of the Mississippi River," where most of the black population was concentrated.[10] Five other districts all had white majorities. While party alignments changed in the 20th century, such gerrymandering has persisted to support white political strength. Claiborne County is within the black-majority 2nd congressional district, as may be seen on the map to the right. The state has three other congressional districts, all white majority. Democrats passed a new constitution in 1890 that included requirements for poll taxes; these and later literacy tests (administered subjectively by whites) were used in practice to disfranchise most blacks and many poor whites, preventing them from registering to vote.[11] This second-class status was enforced by whites until after the civil rights movement gained passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965.[12] The county's economy continued to be based on agriculture. After the Civil War and emancipation, the system of sharecropping developed. More than 80 percent of African-American workers were involved in sharecropping from the late 19th century into the 1930s, shaping all aspects of daily life for them.[13] 20th century to presentExcluded from the political process and suffering lynchings and other violence, many blacks left the county and state in the Great Migration. In 1900 whites numbered 4565 in the county, and blacks 16,222.[5] A local history noted many blacks were leaving the county at that time.[5] As can be seen in the Historical Population table in the "Demographics" section below, from 1900 to 1920, the population of the county declined by 41%, more than 8500 persons from the peak of 20,787. Most of these rural blacks migrated to the industrial North and Midwest cities, such as Chicago, to seek jobs and other opportunities elsewhere. Rural whites also migrated out of the South.[14] Despite the passage of national civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s, African Americans in Claiborne County continued to struggle against white supremacy in most aspects of their lives. The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission continued to try to spy on and disrupt black meetings. "African Americans insisted on dignified treatment and full inclusion in the community's public life, while whites clung to paternalistic notions of black inferiority and defended inherited privilege."[15] In reaction to harassment and violence, in 1966 blacks formed a group, Deacons for Defense, which armed to protect the people and was strictly for self-defense. They learned the law and stayed within it. After shadowing police to prevent abuses, its leaders eventually began to work closely with the county sheriff to keep relations peaceful. In later years, five of the Deacons worked in law enforcement and two were the first blacks to run for county sheriff.[16] In the late 1960s, African Americans struggled to integrate schools, and to register and vote.[17] In 1965 NAACP leader Charles Evers (brother of Medgar, who had been assassinated) became very active in Claiborne County and other areas of southwest Mississippi, including Adams and Jefferson counties. He gained an increase in voter registration as well as increasing membership in the NAACP throughout the region. Evers was influential in a developing a moderate coalition of blacks and white liberals in Mississippi. They wanted to develop alternatives to both the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the all-white Democratic Regulars.[18] In the June 1966 Democratic primary, blacks in Claiborne and Jefferson counties cast decisive majorities, voting for the MFDP candidate, Marcus Whitley, for Congress and giving him victory in those counties. In the November election, Evers led an African-American vote for the Independent senatorial candidate, Prentiss Walker, who won in those counties but lost to incumbent James O. Eastland, a white Democrat.[19] (Claiborne County and southwest Mississippi were then in the Mississippi's 4th congressional district.) Walker was a conservative who in 1964 was elected as the first Republican Congressman from Mississippi in the 20th century, as part of a major realignment of political parties in the South. To gain integration of public facilities and more opportunities in local businesses, where no black clerks were hired, African Americans undertook an economic boycott of merchants in the county seat of Port Gibson. (Similar economic boycotts were conducted in this period in Jackson and Greenville.) Evers led the boycott, enforced its maintenance, and later negotiated with merchants and their representatives on how to end it. While criticized for some of his methods, Evers gained support from the national NAACP for his apparent effectiveness, from the segregationist Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission for negotiating on certain elements, and from local African Americans and white liberals.[4] The boycott was upheld as a legal form of political protest by the United States Supreme Court. The economic boycott was concluded in late January 1967, when merchants agreed to hire blacks as clerks. Nearly two dozen people were hired, and merchants promised more courteous treatment and ease of shopping. In addition, by this time 50 students were attending formerly whites-only public schools. In November 1966 Floyd Collins ran for the school board; he was the county's first black candidate for electoral office since Reconstruction. He was defeated, but a majority of blacks carried the county against Democratic Regular candidates for the Senate and Congress, incumbent senator James Eastland and John Bell Williams.[20] In 1979, Frank Davis was elected as the county's first black sheriff since Reconstruction.[21] Since 2003, when Mississippi had to redistrict because it lost a seat in Congress, Claiborne County has been included in the black-majority 2nd congressional district. Its voters strongly support Democratic candidates. The three other districts are white majority and vote for Republicans. Law enforcementThe Claiborne County Sheriff's Department was formed in 1818, when A. Barnes became Claiborne County's first sheriff. Despite having a majority black population, Claiborne has only had three black sheriffs. In 1874, during the period known as Reconstruction, Thomas Bland became the county's first black sheriff. He served for less than a year. It would be over a hundred years before Claiborne would have another black sheriff when Frank Davis took office in 1979.[21] Davis served until 2012, when Marvin Lucas, the current sheriff, took office.[22] Frank Davis, the current sheriff, took office in January 2016.[22] Politics

GeographyAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 501 square miles (1,300 km2), of which 487 square miles (1,260 km2) is land and 14 square miles (36 km2) (2.8%) is water.[24] Major highways

Adjacent counties

National protected area

Demographics

Population declined from 1940 to 1979 as more African Americans left in the Great Migration. After gains from 1970 to 1980, population has declined since 1980 by nearly 25%. Because of limited economic opportunities in the rural county, residents have left.

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 9,135 people, 2,908 households, and 1,897 families residing in the county. CommunitiesCity

Census-designated placeUnincorporated communitiesGhost townsSites of interest

EducationAll of the county is zoned to the Claiborne County School District.[31] The county is in the district of Hinds Community College.[32] Notable people

See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||