|

Anti-art

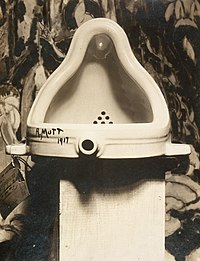

Anti-art is a loosely used term applied to an array of concepts and attitudes that reject prior definitions of art and question art in general. Somewhat paradoxically, anti-art tends to conduct this questioning and rejection from the vantage point of art.[2] The term is associated with the Dada movement and is generally accepted as attributable to Marcel Duchamp pre-World War I around 1914, when he began to use found objects as art. It was used to describe revolutionary forms of art. The term was used later by the Conceptual artists of the 1960s to describe the work of those who claimed to have retired altogether from the practice of art, from the production of works which could be sold.[3][4] An expression of anti-art may or may not take traditional form or meet the criteria for being defined as a work of art according to conventional standards.[5][6] Works of anti-art may express an outright rejection of having conventionally defined criteria as a means of defining what art is, and what it is not. Anti-artworks may reject conventional artistic standards altogether,[7] or focus criticism only on certain aspects of art, such as the art market and high art. Some anti-artworks may reject individualism in art,[8][9] whereas some may reject "universality" as an accepted factor in art. Additionally, some forms of anti-art reject art entirely, or reject the idea that art is a separate realm or specialization.[10] Anti-artworks may also reject art based upon a consideration of art as being oppressive of a segment of the population.[11] Anti-art artworks may articulate a disagreement with the generally supposed notion of there being a separation between art and life. Anti-art artworks may voice a question as to whether "art" really exists or not.[12] "Anti-art" has been referred to as a "paradoxical neologism",[13] in that its obvious opposition to art has been observed concurring with staples of twentieth-century art or "modern art", in particular art movements that have self-consciously sought to transgress traditions or institutions.[14] Anti-art itself is not a distinct art movement, however. This would tend to be indicated by the time it spans—longer than that usually spanned by art movements. Some art movements though, are labeled "anti-art". The Dada movement is generally considered the first anti-art movement; the term anti-art itself is said to have been coined by Dadaist Marcel Duchamp around 1914, and his readymades have been cited as early examples of anti-art objects.[15] Theodor W. Adorno in Aesthetic Theory (1970) stated that "...even the abolition of art is respectful of art because it takes the truth claim of art seriously".[16] Anti-art has become generally accepted by the artworld to be art, although some people still reject Duchamp's readymades as art, for instance the Stuckist group of artists,[3] who are "anti-anti-art".[17][18] Forms Anti-art can take the form of art or not.[5][6] It is posited that anti-art need not even take the form of art, in order to embody its function as anti-art. This point is disputed. Some of the forms of anti-art which are art strive to reveal the conventional limits of art by expanding its properties.[19] Some instances of anti-art are suggestive of a reduction to what might seem to be fundamental elements or building blocks of art. Examples of this sort of phenomenon might include monochrome paintings, empty frames, silence as music, chance art. Anti-art is also often seen to make use of highly innovative materials and techniques, and well beyond—to include hitherto unheard of elements in visual art. These types of anti-art can be readymades, found object art, détournement, combine paintings, appropriation (art), happenings, performance art, and body art.[19] Anti-art can involve the renouncement of making art entirely.[6] This can be accomplished through an art strike and this can also be accomplished through revolutionary activism.[6] An aim of anti-art can be to undermine or understate individual creativity. This may be accomplished through the utilization of readymades.[8] Individual creativity can be further downplayed by the use of industrial processes in the making of art. Anti-artists may seek to undermine individual creativity by producing their artworks anonymously.[20] They may refuse to show their artworks. They may refuse public recognition.[9] Anti-artists may choose to work collectively, in order to place less emphasis on individual identity and individual creativity. This can be seen in the instance of happenings. This is sometimes the case with "supertemporal" artworks, which are by design impermanent. Anti-artists will sometimes destroy their works of art.[9][21] Some artworks made by anti-artists are purposely created to be destroyed. This can be seen in auto-destructive art. André Malraux has developed a concept of anti-art quite different from that outlined above. For Malraux, anti-art began with the 'Salon' or 'Academic' art of the nineteenth century which rejected the basic ambition of art in favour of a semi-photographic illusionism (often prettified). Of Academic painting, Malraux writes, 'All true painters, all those for whom painting is a value, were nauseated by these pictures – "Portrait of a Great Surgeon Operating" and the like – because they saw in them not a form of painting, but the negation of painting'. For Malraux, anti-art is still very much with us, though in a different form. Its descendants are commercial cinema and television, and popular music and fiction. The 'Salon', Malraux writes, 'has been expelled from painting, but elsewhere it reigns supreme'.[22] TheoryAnti-art is also a tendency in the theoretical understanding of art and fine art. The philosopher Roger Taylor puts forward that art is a bourgeois ideology that has its origins with capitalism in "Art, an Enemy of the People". Holding a strong anti-essentialist position he states also that art has not always existed and is not universal but peculiar to Europe.[23] The Invention of Art: A Cultural History by Larry Shiner is an art history book which fundamentally questions our understanding of art. "The modern system of art is not an essence or a fate but something we have made. Art as we have generally understood it is a European invention barely two hundred years old." (Shiner 2003, p. 3) Shiner presents (fine) art as a social construction that has not always existed throughout human history and could also disappear in its turn. HistoryPre World War IJean-Jacques Rousseau rejected the separation between performer and spectator, life and theatre.[24] Karl Marx posited that art was a consequence of the class system and therefore concluded that, in a communist society, there would only be people who engage in the making of art and no "artists".[25]  Arguably the first movement that deliberately set itself in opposition to established art were the Incoherents in late 19th. century Paris. Founded by Jules Lévy in 1882, the Incoherents organized charitable art exhibitions intended to be satirical and humoristic, they presented "...drawings by people who can't draw..."[26] and held masked balls with artistic themes, all in the greater tradition of Montmartre cabaret culture. While short lived – the last Incoherent show took place in 1896 – the movement was popular for its entertainment value.[27] In their commitment to satire, irreverence and ridicule they produced a number of works that show remarkable formal similarities to creations of the avant-garde of the 20th century: ready-mades,[28] monochromes,[29] empty frames[30] and silence as music.[31] Dada and constructivismBeginning in Switzerland, during World War I, much of Dada, and some aspects of the art movements it inspired, such as Neo-Dada, Nouveau réalisme,[32] and Fluxus, is considered anti-art.[33][34] Dadaists rejected cultural and intellectual conformity in art and more broadly in society.[35] For everything that art stood for, Dada was to represent the opposite. Where art was concerned with traditional aesthetics, Dada ignored aesthetics completely. If art was to appeal to sensibilities, Dada was intended to offend. Through their rejection of traditional culture and aesthetics the Dadaists hoped to destroy traditional culture and aesthetics.[36] Because they were more politicized, the Berlin dadas were the most radically anti-art within Dada.[37] In 1919, in the Berlin group, the Dadaist revolutionary central council outlined the Dadaist ideals of radical communism.[38] Beginning in 1913 Marcel Duchamp's readymades challenged individual creativity and redefined art as a nominal rather than an intrinsic object.[39][40] Tristan Tzara indicated: "I am against systems; the most acceptable system is on principle to have none."[41] In addition, Tzara, who once stated that "logic is always false",[42] probably approved of Walter Serner's vision of a "final dissolution".[43] A core concept in Tzara's thought was that "as long as we do things the way we think we once did them we will be unable to achieve any kind of livable society."[44] Originating in Russia in 1919, constructivism rejected art in its entirety and as a specific activity creating a universal aesthetic[45] in favour of practices directed towards social purposes, "useful" to everyday life, such as graphic design, advertising and photography. In 1921, exhibiting at the 5x5=25 exhibition, Alexander Rodchenko created monochromes and proclaimed the end of painting.[46] For artists of the Russian Revolution, Rodchenko's radical action was full of utopian possibility. It marked the end of art along with the end of bourgeois norms and practices. It cleared the way for the beginning of a new Russian life, a new mode of production, a new culture.[47] SurrealismBeginning in the early 1920s, many Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost, with the works being an artifact. Surrealism as a political force developed unevenly around the world, in some places more emphasis being put on artistic practices, while in others political practises outweighed. In other places still, Surrealist praxis looked to overshadow both the arts and politics. Politically, Surrealism was ultra-leftist, communist, or anarchist. The split from Dada has been characterised as a split between anarchists and communists, with the Surrealists as communist. In 1925, the Bureau of Surrealist Research declared their affinity for revolutionary politics.[48] By the 1930s many Surrealists had strongly identified themselves with communism.[49][50][51] Breton and his comrades supported Leon Trotsky and his International Left Opposition for a while, though there was an openness to anarchism that manifested more fully after World War II. Leader André Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was above all a revolutionary movement. Breton believed the tenets of Surrealism could be applied in any circumstance of life, and is not merely restricted to the artistic realm.[52] Breton's followers, along with the Communist Party, were working for the "liberation of man." However, Breton's group refused to prioritize the proletarian struggle over radical creation such that their struggles with the Party made the late 1920s a turbulent time for both. Many individuals closely associated with Breton, notably Louis Aragon, left his group to work more closely with the Communists. In 1929, Breton asked Surrealists to assess their "degree of moral competence", and theoretical refinements included in the second manifeste du surréalisme excluded anyone reluctant to commit to collective action[53] By the end of World War II the surrealist group led by André Breton decided to explicitly embrace anarchism. In 1952 Breton wrote "It was in the black mirror of anarchism that surrealism first recognised itself."[54] Letterism and the Situationist International

Founded in the mid-1940s in France by Isidore Isou, the Letterists utilised material appropriated from other films, a technique which would subsequently be developed (under the title of 'détournement') in Situationist films. They would also often supplement the film with live performance, or, through the 'film-debate', directly involve the audience itself in the total experience. The most radical of the Letterist films, Wolman's The Anticoncept and Debord's Howlings for Sade abandoned images altogether. In 1956, recalling the infinitesimals of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, quantities which could not actually exist except conceptually, the founder of Lettrism, Isidore Isou, developed the notion of a work of art which, by its very nature, could never be created in reality, but which could nevertheless provide aesthetic rewards by being contemplated intellectually. Related to this, and arising out of it, is excoördism, the current incarnation of the Isouian movement, defined as the art of the infinitely large and the infinitely small. In 1960, Isidore Isou created supertemporal art: a device for inviting and enabling an audience to participate in the creation of a work of art. In its simplest form, this might involve nothing more than the inclusion of several blank pages in a book, for the reader to add his or her own contributions. In Japan in the late 1950s, Group Kyushu was an edgy, experimental and rambunctious art group. They ripped and burned canvasses, stapled corrugated cardboard, nails, nuts, springs, metal drill shavings, and burlap to their works, assembled many unwieldy junk assemblages, and were best known for covering much of their work in tar. They also occasionally covered their work in urine and excrement. They tried to bring art closer to everyday life, by incorporating objects from daily life into their work, and also by exhibiting and performing their work outside on the street for everyone to see. Other similar anti-art groups included Neo-Dada (Neo-Dadaizumu Oganaizazu), Gutai (Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai), and Hi-Red-Center. Influenced in various ways by L'Art Informel, these groups and their members worked to foreground material in their work: rather than seeing the art work as representing some remote referent, the material itself and the artists' interaction with it became the main point. The freeing up of gesture was another legacy of L'Art Informel, and the members of Group Kyushu took to it with great verve, throwing, dripping, and breaking material, sometimes destroying the work in the process. Beginning in the 1950s in France, the Letterist International and after the Situationist International developed a dialectical viewpoint, seeing their task as superseding art, abolishing the notion of art as a separate, specialized activity and transforming it so it became part of the fabric of everyday life. From the Situationist's viewpoint, art is revolutionary or it is nothing. In this way, the Situationists saw their efforts as completing the work of both Dada and surrealism while abolishing both.[55][56] The situationists renounced the making of art entirely.[6] The members of the Situationist International liked to think they were probably the most radical,[6][57] politicized,[6] well organized, and theoretically productive anti-art movement, reaching their apex with the student protests and general strike of May 1968 in France, a view endorsed by others including the academic Martin Puchner.[6] In 1959 Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio proposed Industrial Painting as an "industrial-inflationist art"[58] Neo-Dada and laterSimilar to Dada, in the 1960s, Fluxus included a strong current of anti-commercialism and an anti-art sensibility, disparaging the conventional market-driven art world in favor of an artist-centered creative practice. Fluxus artists used their minimal performances to blur the distinction between life and art.[59][60] In 1962 Henry Flynt began to campaign for an anti-art position.[61] Flynt wanted avant-garde art to become superseded by the terms of veramusement and brend – neologisms meaning approximately pure recreation. In 1963 George Maciunas advocated revolution, "living art, anti-art" and "non art reality to be grasped by all peoples".[62] Maciunas strived to uphold his stated aims of demonstrating the artist's 'non-professional status...his dispensability and inclusiveness' and that 'anything can be art and anyone can do it.'[63] In the 1960s, the Dada-influenced art group Black Mask declared that revolutionary art should be "an integral part of life, as in primitive society, and not an appendage to wealth".[64] Black Mask disrupted cultural events in New York by giving made up flyers of art events to the homeless with the lure of free drinks.[65] Later, the Motherfuckers were to grow out of a combination of Black Mask and another group called Angry Arts. The BBC aired an interview with Duchamp conducted by Joan Bakewell in 1966 which expressed some of Duchamps more explicit Anti-Art ideas. Duchamp compared art with religion, whereby he stated that he wished to do away with art the same way many have done away with religion. Duchamp goes on to explain to the interviewer that "the word art etymologically means to do", that art means activity of any kind, and that it is our society that creates "purely artificial" distinctions of being an artist.[66][67][68] During the 1970s, King Mob was responsible for various attacks on art galleries along with the art inside. According to the philosopher Roger Taylor the concept of art is not universal but is an invention of bourgeois ideology helping to promote this social order. He compares it to a cancer that colonises other forms of life so that it becomes difficult to distinguish one from the other.[11] Stewart Home called for an Art Strike between 1990 and 1993. Unlike earlier art-strike proposals such as that of Gustav Metzger in the 1970s, it was not intended as an opportunity for artists to seize control of the means of distributing their own work, but rather as an exercise in propaganda and psychic warfare aimed at smashing the entire art world rather than just the gallery system. As Black Mask had done in the 1960s, Stewart Home disrupted cultural events in London in the 1990s by giving made up flyers of literary events to the homeless with the lure of free drinks.[65] The K Foundation was an art foundation that published a series of Situationist-inspired press adverts and extravagant subversions in the art world. Most notoriously, when their plans to use banknotes as part of a work of art fell through, they burnt a million pounds in cash. Punk has developed anti-art positions. Some "industrial music" bands describe their work as a form of "cultural terrorism" or as a form of "anti-art". The term is also used to describe other intentionally provocative art forms, such as nonsense verse. As artParadoxically, most forms of anti-art have gradually been completely accepted by the art establishment as normal and conventional forms of art.[69] Even the movements which rejected art with the most virulence are now collected by the most prestigious cultural institutions.[70] Duchamp's readymades are still regarded as anti-art by the Stuckists,[3] who also say that anti-art has become conformist, and describe themselves as anti-anti-art.[17][18] See also

References

Sources

Further reading

External links

|