|

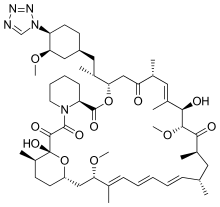

Zotarolimus

Zotarolimus (INN, codenamed ABT-578) is an immunosuppressant. It is a semi-synthetic derivative of sirolimus (rapamycin). It was designed for use in stents with phosphorylcholine as a carrier. Zotarolimus, or ABT-578, was originally used on Abbott's coronary stent platforms to reduce early inflammation and restenosis; however, Zotarolimus failed Abbott's primary endpoint to bring their stent/drug delivery system to market. The drug was sold/distributed to Medtronic for use on their stent platforms, which is the same drug they use today. Coronary stents reduce early complications and improve late clinical outcomes in patients needing interventional cardiology.[1] The first human coronary stent implantation was first performed in 1986 by Puel et al.[1][2] However, there are complications associated with stent use, development of thrombosis which impedes the efficiency of coronary stents, haemorrhagic and restenosis complications are problems associated with stents.[1] These complications have prompted the development of drug-eluting stents. Stents are bound by a membrane consisting of polymers which not only slowly release zotarolimus and its derivatives into the surrounding tissues but also do not invoke an inflammatory response by the body. Medtronic are using zotarolimus as the anti-proliferative agent in the polymer coating of their Endeavor and Resolute products.[3] BackgroundThe inherent growth inhibitory properties of many anti-cancer agents make these drugs ideal candidates for the prevention of restenosis. However, these same properties are often associated with cytotoxicity at doses which block cell proliferation. Therefore, the unique cytostatic nature of the immunosuppressant rapamycin was the basis for the development of zotarolimus by Johnson and Johnson. Rapamycin was originally approved for the prevention of renal transplant rejection in 1999. More recently, Abbott Laboratories developed a compound from the same class, zotarolimus (formerly ABT-578), as the first cytostatic agent to be used solely for delivery from drug-eluting stents to prevent restenosis.[4] Drug-eluting stentsDrug-eluting stents have revolutionized the field of interventional cardiology and have provided a significant innovation for preventing coronary artery restenosis. Polymer coatings that deliver anti-proliferative drugs to the vessel wall are key components of these revolutionary medical devices. The development of stents which elute the potent anti-proliferative agent, zotarolimus, from a synthetic phosphorylcholine-based polymer known for its biocompatible profile. Zotarolimus is the first drug developed specifically for local delivery from stents for the prevention of restenosis and has been tested extensively to support this indication. Clinical experience with the PC polymer is also extensive, since more than 120,000 patients have been implanted to date with stents containing this non-thrombogenic coating.[4] Structure and propertiesZotarolimus is an analog made by substituting a tetrazole ring in place of the native hydroxyl group at position 42 in rapamycin that is isolated and purified as a natural product from fermentation. This site of modification was found to be the most tolerant position to introduce novel structural changes without impairing biologic activity. The compound is extremely lipophilic, with a very high octanol-water partition coefficient, and therefore has limited water solubility. These properties are highly advantageous for designing a drug-loaded stent containing zotarolimus in order to obtain a slow sustained release of drug from the stent directly into the wall of coronary vessels. The poor water solubility prevents rapid release into the circulation, since elution of drug from the stent will be partly dissolution rate-limited. The slow rate of release and subsequent diffusion of the molecule facilitates the maintenance of therapeutic drug levels eluting from the stent. In addition, its lipophilic character favors crossing cell membranes to inhibit neointimal proliferation of target tissue. The octanol-water partition coefficients of a number of compounds, recently obtained in a comparative study, indicate that zotarolimus is the most lipophilic of all DES drugs [4] RestenosisZotarolimus is used to counteract restenosis. Restenosis is typically described by clinical trials in a binary approach, otherwise known as "binary restenosis" or just "binary stenosis." Binary restenosis is defined as a >50% stenosis in the vessel diameter (diameter stenosis), or >50% loss of the acute luminal gain, also known as "late loss" following the "acute gain" in lumen diameter after stenting.[1] The term "binary" means that patients are placed in 2 groups, those who have >50% stenosis, and those who have <50% stenosis. An occlusion, or the blocking of all blood flow through a vessel, is considered 100% stenosis. Previously, restenosis was thought to arise due to the development of neointimal thickening as a result of smooth muscle stimulation.[1] However, it is now thought the blood vessel's dilated segment shrinking is the mechanism.[1] This explains why stenting, which increases the luminal area, is so effective in decreasing the occurrence of restenosis.[1] Vessel restenosis is typically detected by angiography, but can also be detected by duplex ultrasound and other imaging techniques. Restenosis preventionThe major advancement in restenosis prevention is the use of stents. The Stent Restenosis Study (STRESS) indicated that stents lower restenosis incidence to 32% compared to other medical techniques which combine to only lower it to 42%.[1] Physiological effectsThe key biologic event associated with the restenotic process is clearly the proliferation of smooth muscle cells in response to the expansion of a foreign body against the vessel wall. This proliferative response is initiated by the early expression of growth factors such as PDGF isoforms, bFGF, thrombin, which bind to cellular receptors. However, the key to understanding the mechanism by which compounds like zotarolimus inhibit cell proliferation is based on events which occur downstream of this growth factor binding. The signal transduction events which culminate in cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase are initiated as a result of ligand binding to an immunophilin known as FK binding protein-12. The FK designation was based on early studies conducted with tacrolimus, formerly known as FK-506, which binds this cytoplasmic protein with high affinity. Subsequent investigations showed that rapamycin also binds to this intracellular target, forming an FKBP12–rapamycin complex which is not in itself inhibitory, but does have the capacity to block an integral protein kinase known as target of rapamycin (TOR). TOR was first discovered in yeast[5] and later identified in eukaryotic cells, where it was designated as mTOR, the mammalian target of rapamycin. The importance of mTOR is based on its ability to phosphorylate a number of key proteins, including those associated with protein synthesis (p70s6kinase) and initiation of translation (4E-BP1). Of particular significance is the role that mTOR plays in the regulation of p27kip1, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases such as cdk2. The binding of agents like rapamycin and zotarolimus to mTOR is thought to block mTOR's crucial role in these cellular events, resulting in arrest of the cell cycle, and ultimately, cell proliferation. References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||