|

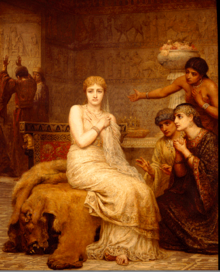

Vashti

Vashti (Hebrew: וַשְׁתִּי, romanized: Vaštī; Koinē Greek: Ἀστίν, romanized: Astín; Modern Persian: واشتی, romanized: Vâšti) was a queen of Persia and the first wife of Persian king Ahasuerus in the Book of Esther, a book included within the Tanakh and the Old Testament which is read on the Jewish holiday of Purim. She was either executed or banished for her refusal to appear at the king's banquet to show her beauty as Ahasuerus wished, and was succeeded as queen by Esther, a Jew. That refusal might be better understood via the Jewish tradition that she was ordered to appear naked. In the Midrash, Vashti is described as wicked and vain; she is viewed as an independent-minded heroine in feminist theological interpretations of the Purim story. Attempts to identify her as one of the Persian royal consorts mentioned in extra-biblical records remain speculative. Etymology and meaningHoschander proposed that it originated as a shortening of an unattested "vashtateira", which he also proposed as the origin of the name "Stateira".[1] In the Book of Esther In the Book of Esther, Vashti is the first wife of King Ahasuerus. While the king holds a magnificent banquet for his princes, nobles and servants, she holds a separate banquet for the women. On the seventh day of the banquet, when the king's heart was "merry with wine", the king orders his seven chamberlains to summon Vashti to come before him and his guests wearing her royal crown, in order to display her beauty. Vashti refuses to come, and the king becomes angry. He asks his advisers how Vashti should be punished for her disobedience. His adviser Memucan tells him that Vashti has wronged not only the king, but also all of the husbands of Persia, whose wives may be encouraged by Vashti's actions to disobey. Memucan encourages Ahasuerus to dismiss Vashti and find another queen. Ahasuerus takes Memucan's advice, and sends letters to all of the provinces that men should dominate in their households. Ahasuerus subsequently chooses Esther as his queen to replace Vashti.[2] King Ahasuerus's command for the appearance of Queen Vashti is interpreted by several midrashic sources as an order to appear unclothed for the attendees of the king's banquet.[3] Historical identification Because the text lacks any references to known events, some historians believe that the narrative of Esther is fictional, and the name Ahasuerus is used to refer to a fictionalized Xerxes I, in order to provide an aetiology for Purim. Some historians additionally argue that, because the Persian kings did not marry outside a handful of Persian noble families, it is unlikely that there was a Jewish queen Esther and that in any case the historical Xerxes's queen was Amestris.[4][5][6] That being said, many Jews believe the story to be a true historical event, especially Persian Jews who have a close relationship to Esther. In the Septuagint, the Book of Esther refers to this king as 'Artaxerxes' (Ancient Greek: Αρταξέρξης).[7] In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Bible commentators attempted to identify Vashti with Persian queens mentioned by the Greek historians. Traditional sources identify Ahasuerus with Artaxerxes II of Persia. Jacob Hoschander, supporting the traditional identification, suggested that Vashti may be identical to a wife of Artaxerxes mentioned by Plutarch, named Stateira.[1] Upon the discovery of the equivalence of the names Ahasuerus and Xerxes, some Bible commentators began to identify Ahasuerus with Xerxes I and Vashti with the wife named Amestris mentioned by Herodotus.[8] In the MidrashAccording to the Midrash, Vashti was the great-granddaughter of King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon, the granddaughter of King Amel-Marduk and the daughter of King Belshazzar. During Vashti's father's rule, mobs of Medes and Persians attacked. They murdered Belshazzar that night. Vashti, unknowing of her father's death, ran to her father's quarters. There she was kidnapped by King Darius of Persia. But Darius took pity on her and gave her to his son, Ahasuerus, to marry. Based on Vashti's descent from a King who was responsible for the destruction of the temple as well as on her unhappy fate, the Midrash presents Vashti as wicked and vain. Since Vashti is ordered to appear before the king on the seventh day of the feast, the rabbis argued that Vashti enslaved Jewish women and forced them to work on the Sabbath. They attribute her unwillingness to appear before the king and his drinking partners not to modesty, but rather to an affliction with a disfiguring illness. One account relates that she suffered from leprosy, while another states that the angel Gabriel came and "fixed a tail on her." The latter possibility is often interpreted as "a euphemism for a miraculous transformation to male anatomy."[9] According to the Midrashic account, Vashti was a clever politician, and the ladies' banquet that she held in parallel to Ahasuerus' banquet represented an astute political maneuver. Since the noble women of the kingdom would be present at her banquet, she would have control of a valuable group of hostages in case a coup d'état occurred during the king's feast.[9] R. Abba b. Kahana says Vashti was no more modest than Ahasuerus. R. Papa quotes a popular proverb: "He between the old calabashes, and she between the young ones"; i.e., a faithless husband makes a faithless wife. According to R. Jose b. Ḥanina, Vashti declined the invitation because she had become a leper (Meg. 12b; Yalḳ., l.c.). Ahasuerus was "very wroth, and his anger burned in him" (Esth. i. 12) as the result of the insulting message which Vashti sent him: "Thou art the son of my father's stableman. My grandfather [Belshazzar] could drink before the thousand [Dan. v. 1]; but that person [Ahasuerus] quickly becomes intoxicated" (Meg. l.c.). Vashti was justly punished for enslaving young Jewish women and compelling them to work nude on the Sabbath (ib.).[10] As a feminist iconVashti's refusal to obey the summons of her drunken husband has been admired as heroic in many feminist interpretations of the Book of Esther. Early feminists admired Vashti's principle and courage. Harriet Beecher Stowe called Vashti's disobedience the "first stand for woman's rights."[11] Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote that Vashti "added new glory to [her] day and generation...by her disobedience; for 'Resistance to tyrants is obedience to God.'"[12] Some more recent feminist interpreters of the Book of Esther compare Vashti's character and actions favorably to those of her successor, Esther, who is traditionally viewed as the heroine of the Purim story. Michele Landsberg, a Canadian Jewish feminist, writes: "Saving the Jewish people was important, but at the same time [Esther's] whole submissive, secretive way of being was the absolute archetype of 1950s womanhood. It repelled me. I thought, 'Hey, what's wrong with Vashti? She had dignity. She had self-respect. She said: 'I'm not going to dance for you and your pals.'"[13] Popular culture

References

External links

|

||||||||||||