|

Tritrichomonas foetus

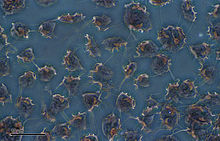

Tritrichomonas foetus is a species of single-celled flagellated parasites that is known to be a pathogen of the bovine reproductive tract as well as the intestinal tract of cats. In cattle, the organism is transmitted to the female vagina and uterus from the foreskin of the bull where the parasite is known to reside. It causes infertility, and, at times, has caused spontaneous abortions in the first trimester. In the last ten years, there have been reports of Tritrichomonas foetus in the feces of young cats that have diarrhea[1] and live in households with multiple cats. Tritrichomonas foetus looks similarly to Giardia and is often misdiagnosed for it when viewed under a microscope.[2] CauseTritrichomonas foetus is the genus Tritrichomonas within the order Tritrichomonadida in the Kingdom Protoctista. The parasite is 5-25 μm in size and is spindle shaped with four flagella, which are whiplike projections, and an undulating or wavy membrane. Three of the flagella are found on the anterior end and approximately the same length as the body of the parasite. The fourth is on the posterior end.[3] Their movement is jerky and in a forward direction, and they also do "barrel rolls". The organisms look like small tadpoles with small tails when viewed microscopically. The parasite interacts with bacteria that normally reside in the intestinal tract by adhering to the intestinal epithelium of the host. CattleClinical signsBulls do not show any clinical signs of infections and can infect females at mating. In cows, there may be infertility, embryonic death and abortion, and reproductive tract infections such as pyometra.[4][5] Cows may show outward signs of infection, namely a sticky, white vaginal discharge, which may occur for up to two months after the initial infection. The disease results in abortion of the embryo, often within ten days of conception. Evidence of repeat breeding or infertility may be a sign of trichomoniasis. After the abortion of the fetus and the cow's return to a normal estrous cycle, the cow may come into estrus again, at which point it may be bred again. Eventually the cow will be able to cycle normally and carry a fetus to term. However, the irregularities after initial infection present obvious clinical signs of reproductive inconsistencies, which should be examined by a veterinarian immediately.[6] Bulls remain infected for life, but cows can successfully clear the infection, but reinfection is likely.[7] DiagnosisDiagnosis can be done on both males and females; however, bulls are tested more since they remain carriers. In cattle, a presumptive diagnosis can be made from the signs of infertility and geography. Diagnosis may rely on microscopic examination of vaginal or preputial smears. Complement fixation can be performed to detect parasite antibodies in vaginal secretions.[5] Several related trichomonads may be mistaken for Tritrichomonas foetus, including: Trichomonas vaginalis, Trichomonas gallinae, and Trichomonas tenax. A study by Richard Felleisen found that identification of T. foetus using Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) resulted in a more accurate identification. The 5.8S rRNA gene of T. foetus was found to have 12 copies in the T. foetus genome. This indicated that the organism could be identified via amplification of this gene by PCR. Not only would this allow for identification of T. foetus, but also differentiation from other trichomonad species.[6] Diagnosis can also be done using the InPouch TF from a prepuce scraping sample from a bull. Treatment and ControlBulls can be treated in different ways. Various imidazoles have been used, but none are both safe and effective in treatment. Ipronidazole is probably most effective but, due to its low pH, frequently causes sterile abscesses at injection sites. Bulls can also remain carriers for life and can easily be susceptible to reinfection even after successful treatment. However bulls can sometimes remain carriers for life once they become infected. Cows can be treated by being left alone for around three months to allow them time to shed the vaginal and uterine lining that is affected. Semen can also be treated successfully with dimetridazole and then used for artificial insemination. Commercially available vaccines (TrichGuard,[8] Tricovac[9]) cannot prevent infection, but confer disease attenuation and some level of protection against complications.[10][11] In a placebo-controlled trial of TrichGuard with forty prophylactically vaccinated, T. foetus-infected beef heifers, 95% of the heifers in the active treatment group conceived, as opposed to 70% in the placebo group. 50% in the TrichGuard-group gave birth to a live calf, compared to 20% in the placebo group.[12] The most effective control method for eliminating the infection in a herd or an individual remains by culling the animal(s) and replacing them with virgin animals after positive test results. Cows can remain in the herd if given enough time to shed the infection or can be culled like bulls to allow faster turnover and assure the herd is clear of the infection.[2][3] TransmissionThere are two routes of direct transmission for Tritrichomonas foetus between cattle: cow-to-bull or bull-to-cow. The most common route of transmission is from bull to cow. The cow can get infected either when naturally bred to an infected bull or when receiving semen from an infected bull during artificial insemination. However, in the case of artificial insemination, while T. foetus is capable of surviving the process used to freeze semen after collection, it is usually killed by drying or high temperatures. In cow-to-bull transmission, a female that has already been infected with T. foetus is bred with a male, who then contracts the infection.[13] Tritrichomonas foetus in cattle is often attributed to direct transmission via reproduction with an infected individual; however, studies have documented evidence of T. foetus persisting in the intestinal tract of the housefly, suggesting a possible mode of transmission outside of reproduction.[14] Tests performed on feline T. foetus have also shown its persistence in room temperature, humid environments for up to ten days.[15] PrognosisThe prognosis for cattle is not good. Infected bulls are advised to be culled; cows should also be culled due to easy reinfection even after clearing the initial infection. Trichomoniasis is a reportable disease in cattle, and as of now, there is no effect treatment. Prevention and smart farm practices are the only remedy. Testing should be done on any bull prior to exposing it to the herd. Limiting exposure of the herd to other cattle and limiting the introduction of open cows into the herd are good preventative practices. An estimated 42% of cows will acquire the disease if bred to an infected bull.[16] CatClinical signsIn cats, Tritrichomonas foetus is characterized by diarrhea that comes and goes and may contain blood and mucus at times. The diarrhea is semi formed in a cow pie consistency. In most cases it affects cats of 12 months of age or younger and cats from rescue shelters and homes with multiple cats. Close and direct contact appears to be the mode in which the parasite is transmitted. Tritrichomonas foetus is most common in purebred felines, breeds like Bengals, Persians, etc. Since catteries tend to trade queens and studs to provide greater genetic diversity, the parasite can be spread from one cattery to another. Doctor Jody L. Gookin and her colleagues identified Tritrichomonas foetus, which causes diarrhea in domestic cats. As a result of her research people are able to diagnose, and a treat the infection.[17] However, just because the cat doesn't show signs of diarrhea, it still could possibly be infected. Adult cats are less likely to develop diarrhea when infected, but they will still serve as a source of infection for other cats. Clinical signs can show up anywhere from days to years after exposure.[18] DiagnosisIn cats, Tritrichomonas foetus can be detected by the following four methods:

Treatment and ControlOne treatment that has been effective in experimentally infected cats is ronidazole but this remains an unapproved use. TransmissionThe primary transmission route is the litter box that is shared by both infected and uninfected cats, where a well-timed use by two cats can transfer the parasite from the feces of one cat to the paws of another where they later become ingested during the act of grooming. In cats, Tritrichomonas foetus is able to live several days in wet stool. Mutual grooming may also transfer the parasite. There is no evidence that T. foetus is sexually transmitted or infects the reproductive tract or mammary glands of cats.[18] PrognosisThe long term prognosis for cats with TF is generally good, the diarrhoea will usually resolve itself in untreated cats. However this can take many months, and cats which no longer show clinical signs can continue to shed the organism for up to two years.[19] It appears that over time the parasite dies off and the infection is remedied on its own. In some cases, the symptoms may improve over time, but the animal is likely to still be a carrier of the parasite, capable of transmitting it to another cat. References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||