|

Trieste (bathyscaphe)

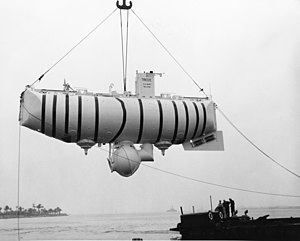

Trieste is a Swiss-designed, Italian-built deep-diving research bathyscaphe. In 1960, it became the first crewed vessel to reach the bottom of Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, the deepest point in Earth's seabed.[2] The mission was the final goal for Project Nekton, a series of dives conducted by the United States Navy in the Pacific Ocean near Guam. The vessel was piloted by Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard and US Navy lieutenant Don Walsh. They reached a depth of about 10,916 metres (35,814 ft). The bathyscaphe was designed by Swiss scientist Auguste Piccard, the father of pilot Jacques Piccard. It was built in Italy and first launched in 1953. The vessel was first owned and operated by the French Navy until it was purchased by the US Navy in 1958. It was taken out of service in 1966. Since the 1980s, it has been on exhibit in the National Museum of the United States Navy in Washington, D.C. Design

Trieste was designed by the Swiss scientist Auguste Piccard, based on his previous experience with the bathyscaphe FNRS-2. The term bathyscaphe refers to its capacity to dive and manoeuvre untethered to a ship in contrast to a bathysphere, bathys being ancient Greek meaning "deep" and scaphe being a light, bowl-shaped boat.[3]

Built in Italy and launched on 26 August 1953 near the Isle of Capri on the Mediterranean Sea[4] it was operated in the Mediterranean by the French Navy for several years until it was purchased by the United States Navy in 1958 for US$250,000, equivalent to $2.6 million today.[5]

Trieste consisted of a heavy crew sphere suspended from a hull containing tanks filled with gasoline (petrol) for buoyancy, ballast hoppers filled with iron shot and floodable water tanks to sink.[6] This general configuration remained the same but after modifications to the hull for Project Nekton, which included the dive to Challenger Deep, Trieste was more than 15 metres (49 ft) long.

The hull was built by Cantieri Riuniti dell'Adriatico, in the Free Territory of Trieste on the border between Italy and Yugoslavia, now in Italy, hence the name. The pressure sphere was built separately and installed on the hull in the Cantiere navale di Castellammare di Stabia, near Naples.  The pressure sphere was attached to the underside of the hull and accommodated two crew who accessed it via a vertical shaft through the hull; this access shaft was not pressurized and flooded with seawater on descent. The sphere was completely self-contained, having a closed-circuit rebreather system with oxygen provided from cylinders while carbon dioxide was scrubbed from the air by being passed through canisters of soda-lime. Batteries provided electrical power. Piccard's original pressure sphere was built by Acciaierie, Terni of steel forged in two hemispheres and welded to form a sphere 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) in diameter and 89 millimetres (3.5 in) thick,[7] This pressure sphere was replaced in December 1958 with another cast by the Krupp Steel Works[8] of Essen, Germany in three sections; an equatorial ring and two caps, which were finely machined and joined by the Ateliers de Constructions Mécaniques de Vevey. The new sphere was also steel, but smaller at 2.16 metres (7.1 ft) diameter and with thicker walls, at 127 millimetres (5.0 in),[5] calculated to withstand the 1,250 kilograms per square centimetre (123 MPa) pressure at the bottom of Challenger Deep plus a substantial factor of safety. The new sphere weighed 14.25 metric tons (31,400 pounds) in air and eight metric tons (18,000 pounds) in water giving it an average specific gravity 2.6 times (or 1.6 times greater than) that of seawater (13÷(13−8)).[9][10] Outside observations by the crew were made through a porthole made from a single, tapered block of acrylic glass; the only transparent material available that could withstand the pressure. Outside illumination was by quartz arc-light bulbs, which could withstand the pressure without modification.[11]  The buoyancy tanks were filled with gasoline, which floats in water and is similarly incompressible. Changes in the volume of the gasoline caused by any slight compression or temperature changes were accommodated by the free flow of seawater into and out of the bottom of the tanks during a dive via valves, equalising the pressure and allowing them to be lightly built. The Mariana Trench dives Trieste departed San Diego on 5 October 1959 for Guam aboard the freighter Santa Maria to participate in Project Nekton, a series of very deep dives in the Mariana Trench. On 23 January 1960, it reached the ocean floor in the Challenger Deep (the deepest southern part of the Mariana Trench), carrying Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh.[13] This was the first time a vessel, crewed or uncrewed, had reached the deepest known point of the Earth's oceans. The onboard systems indicated a depth of 11,521 metres (37,799 ft), although this was revised later to 10,916 metres (35,814 ft); fairly recently, more accurate measurements have found Challenger Deep to be between 10,911 metres (35,797 ft) and 10,994 metres (36,070 ft) deep.[14] The descent to the ocean floor took 4 hours 47 minutes at a descent rate of 0.9 metres per second (3.2 km/h; 2.0 mph).[15][16] After passing 9,000 metres (30,000 ft), one of the outer Plexiglas window panes cracked, shaking the entire vessel.[17] The two men spent twenty minutes on the ocean floor. The temperature in the cabin was 7 °C (45 °F) at the time. While at maximum depth, Piccard and Walsh unexpectedly regained the ability to communicate with the support ship, USS Wandank (ATA-204), using a sonar/hydrophone voice communications system.[18] At a speed of almost 1.6 km/s (1 mi/s) – about five times the speed of sound in air – it took about seven seconds for a voice message to travel from the craft to the support ship and another seven seconds for answers to return. While at the bottom, Piccard and Walsh reported observing a number of sole and flounder (both flatfish).[19][20] The accuracy of this observation has later been questioned and recent authorities do not recognize it as valid.[21] The theoretical maximum depth for fish is at about 8,000–8,500 m (26,200–27,900 ft), beyond which they would become hyperosmotic.[22][23][24] Invertebrates such as sea cucumbers, some of which potentially could be mistaken for flatfish, have been confirmed at depths of 10,000 m (33,000 ft) and more.[22][25] Walsh later said that their original observation could be mistaken as their knowledge of biology was limited.[23] Piccard and Walsh noted that the floor of the Challenger Deep consisted of "diatomaceous ooze". The ascent took 3 hours and 15 minutes. The National Museum of the Navy commemorated the 60th anniversary of the dive in January 2020.[26] Other deep dives and retirement The Trieste performed a number of deep dives in the Mediterranean prior to being purchased by the U.S. Navy in 1958.[4] It conducted 48 dives exceeding 3,700 metres (12,100 ft) between 1953 and 1957 as the Batiscafo Trieste. Beginning in April 1963, Trieste was modified and used in the Atlantic Ocean to search for the missing nuclear submarine USS Thresher (SSN-593).[10] Trieste was delivered to Boston Harbor by USS Point Defiance (LSD-31) under the command of Captain H. H. Haisten. In August 1963, Trieste found debris of the wreck off the coast of New England, 2,560 m (8,400 ft) below the surface after several dives.[10][27] Trieste's participation in the search earned it the Navy Unit Commendation. Following the mission, Trieste was returned to San Diego and taken out of service in 1966.[10][28] Between 1964 and 1966, Trieste was used to develop its replacement, the Trieste II, with the original Terni pressure sphere reincorporated in its successor.[4][29] In early 1980, it was transported to the Washington Navy Yard where it remains on exhibit today in the National Museum of the U.S. Navy, along with the Krupp pressure sphere.[26] Awards

See also

Notes and references

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Trieste (submarine, 1953).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||