|

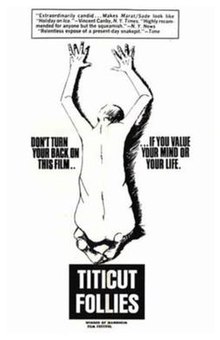

Titicut Follies

Titicut Follies is a 1967 American direct cinema documentary film produced, written, and directed by Frederick Wiseman and filmed by John Marshall. It deals with the patient-inmates of Bridgewater State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, a Massachusetts Correctional Institution in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The title is taken from that of a talent show put on by the hospital staff. Titicut is the Wampanoag name for the nearby Taunton River. The film won accolades in Germany and Italy. Wiseman went on to produce many more such films examining social institutions (e.g. hospitals, police, schools, etc.) in the United States. In 2022, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[2] SynopsisTiticut Follies portrays the occupants of Bridgewater State Hospital, who are often kept in barren cells and infrequently bathed. It also depicts inmates/patients required to strip naked publicly, force feeding, and the indifference and bullying by many of the hospital's staff. The film employs methods of direct cinema, which emphasizes observation, limited stylization, and non-intervention by filmmakers.[3] ProductionDevelopmentTiticut Follies was the beginning of the documentary career of Frederick Wiseman, a Boston-born lawyer turned filmmaker. He had taken his law classes from Boston University to the institution for educational purposes and had "wanted to do a film there". He began calling the facility superintendent, seeking permission to film a year prior to production. Wiseman had previously produced The Cool World (1964), based on Warren Miller’s novel of the same name, an experience that informed his desire to direct. FilmingWiseman drafted a proposal that was verbally agreed to by the superintendent, which later came into question when the film began distribution. Following that agreement, filming began, with corrections staff following Wiseman at all times and determining on the spot whether the subjects filmed were mentally competent, adding further confusion to an already fraught process.[4] While on location, Wiseman recorded the sound and directed the cameraman — established ethnographic filmmaker John Marshall — via microphone or by hand.[5] Post-productionTwenty-nine days were spent documenting the conditions at Bridgewater and 80,000 feet of film were shot. Wiseman spent approximately a year editing the footage into the final 84-minute narrative.[4] Wiseman edited the film in secret, working after hours in the editing rooms at WGBH-TV.[6] ReleaseCensorshipJust before the film was to be shown at the 1967 New York Film Festival, the Massachusetts government tried to procure an injunction banning its release,[7] claiming that the film violated the patients' privacy and dignity.[8] Despite Wiseman having received permission from all the people portrayed or that of the hospital superintendent (the inmates' legal guardian), Massachusetts claimed that this permission could not take the place of release forms from the inmates.[9] Wiseman was also accused of breaching an "oral contract", giving the state government editorial control over the film.[7] A New York state court allowed the screening,[8] but in 1968, Massachusetts Superior Court judge Harry Kalus ordered the film to be recalled from distribution and all copies destroyed, once more citing the state's concerns about violations of the patients' privacy and dignity.[10] Wiseman appealed to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, which in 1969 allowed it to be shown only to doctors, lawyers, judges, health-care professionals, social workers, and students in these and related fields.[7] Wiseman appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case.[9] Wiseman believes that the government of Massachusetts (concerned that the film portrayed a state institution in a bad light) intervened to protect its reputation. The state intervened after a social worker in Minnesota wrote to Massachusetts governor John Volpe, expressing shock at a scene involving a naked man being taunted by a guard.[7] The dispute was the first known instance of a film being banned from general American distribution for reasons other than obscenity, immorality, or national security.[11] It was also the first time that Massachusetts recognized a right to privacy at the state level.[10] Wiseman has said, "The obvious point that I was making was that the restriction of the court was a greater infringement of civil liberties than the film was an infringement on the liberties of the inmates."[10] Little changed until 1987, when the families of seven inmates who had died at the hospital sued the hospital and state. Steven Schwartz represented one of the inmates, who was "restrained for 2½ months and given six psychiatric drugs at vastly unsafe levels—choked to death because he could not swallow his food."[12] Schwartz has said "There is a direct connection between the decision not to show that film publicly and my client dying 20 years later, and a whole host of other people dying in between,"[12] "... in the years since Mr. Wiseman made Titicut Follies, most of the nation's big mental institutions have been closed or cut back by court orders"[13] and "the film may have also influenced the closing of the institution featured in the film."[14] In 1991, Superior Court judge Andrew Meyer allowed the film's release to the general public, saying that as time had passed, privacy concerns had become less important than First Amendment concerns. He also said that many of the former patients had died, so there was little risk of a violation of their dignity.[8] The state Supreme Court ordered that "A brief explanation shall be included in the film that changes and improvements have taken place at Massachusetts Correctional Institution Bridgewater since 1966."[15] The film was shown on PBS on September 4, 1992, its first American television airing. Before, a narrative warning and an introduction by Charlie Rose were played. Following the broadcast, a message was shown stating that improvements had been made since the time of production. The film is now legally available through its distributor, Zipporah Films Inc., for purchase or rental on DVD and for educational and individual license. Zipporah released the DVD to the home market in December 2007. In 2020, the film was shown on Turner Classic Movies. In 2022, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[2] Accolades

ReceptionReview aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports that 100% of 12 critics gave the film a positive review, with an average rating of 7.9/10.[16] See also

ReferencesNotes

Bibliography

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||