|

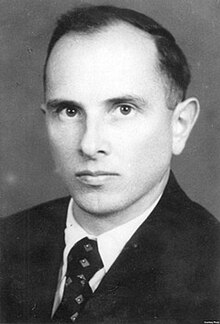

Stepan Bandera

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera (Ukrainian: Степа́н Андрі́йович Банде́ра, IPA: [steˈpɑn ɐnˈd⁽ʲ⁾r⁽ʲ⁾ijoʋɪt͡ʃ bɐnˈdɛrɐ]; Polish: Stepan Andrijowycz Bandera;[1] 1 January 1909 – 15 October 1959) was a Ukrainian far-right leader of the radical militant wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN-B.[2][3] Bandera was born in Austria-Hungary, in Galicia, into the family of a priest of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, and grew up in Poland.[4] Involved in nationalist organizations from a young age, he joined the Ukrainian Military Organization in 1924. In 1931, he became head of propaganda of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), and later became head of the OUN for Poland in 1932. In 1934, he organized the assassination of the Polish interior minister, Bronisław Pieracki, and was sentenced to death after being convicted of terrorism, subsequently commuted to life imprisonment. Bandera was freed from prison in 1939 following the invasion of Poland, and moved to Kraków. In 1940, he became head of the radical faction of the OUN, the OUN-B. On 22 June 1941, the same day Germany invaded the Soviet Union, he formed the Ukrainian National Committee. The head of the Committee, Yaroslav Stetsko, announced the creation of a Ukrainian state on 30 June 1941, in German-captured Lviv. The proclamation pledged to work with Nazi Germany.[5] The Germans disapproved of the proclamation, and for his refusal to rescind the decree, Bandera was arrested by the Gestapo. He was released in September 1944 by the Germans in hope that he could fight the Soviet advance. Bandera negotiated with the Nazis to create the Ukrainian National Army and the Ukrainian National Committee in March 1945.[6] After the war, Bandera settled with his family in West Germany. In 1959, Bandera was assassinated by a KGB agent in Munich.[7][8] Bandera remains a highly controversial figure in Ukraine.[9] Many Ukrainians hail him as a role model hero,[10][11] or as a martyred liberation fighter,[12] while other Ukrainians, particularly in the south and east, condemn him as a fascist,[13] or Nazi collaborator,[10] whose followers, called Banderites, were responsible for massacres of Polish and Jewish civilians during World War II.[14][15] On 22 January 2010, Viktor Yushchenko, the then president of Ukraine, awarded Bandera the posthumous title of Hero of Ukraine, which was widely condemned. The award was subsequently annulled in 2011 given that Stepan Bandera was never a Ukrainian citizen.[16] The controversy regarding Bandera's legacy gained further prominence following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[17][18][19] BiographyEarly life and education Stepan Andriyovych Bandera was born on 1 January 1909 in Staryi Uhryniv, in the region of Galicia in Austria-Hungary, to Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church priest Andriy Bandera (1882–1941) and Myroslava Głodzińska (1890–1921). Bandera had seven siblings, three sisters and four brothers.[20] Bandera's younger brothers included Oleksandr, who earned a doctorate in political economy at the University of Rome, and Vasyl, who finished a degree in philosophy at the University of Lviv. Bandera grew up in a patriotic and religious household.[21] He did not attend primary school due to World War I and was taught at home by his parents.[21] At a young age, Bandera was undersized and slim.[1] He sang in a choir, played guitar and mandolin, enjoyed hiking, jogging, swimming, ice skating, basketball and chess.[22]  After the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in the wake of World War I, Eastern Galicia briefly became part of the West Ukrainian People's Republic. Bandera's father, who joined the Ukrainian Galician Army as a chaplain, was active in the nationalist movement preceding the Polish–Ukrainian War, which was fought between November 1918 to July 1919 and ended with Ukrainian defeat and incorporation of Eastern Galicia into Poland. Mykola Mikhnovsky's 1900 publication, Independent Ukraine, influenced Bandera greatly.[23] After graduating from a Ukrainian high school in Stryi in 1927, where he was engaged in a number of youth organizations, Bandera planned to attend the Husbandry Academy in Czechoslovakia, but he either did not get a passport or the Academy notified him that it was closed.[22] In 1928, Bandera enrolled in the agronomy program at the Politechnika Lwowska in its branch in Dubliany, but never completed his studies due to his political activities and arrests.[24] Early activities Bandera associated himself with a variety of Ukrainian organizations during his time in high school, particularly Plast, Sokil, and Organization of the Upper Grades of the Ukrainian High Schools (OVKUH).[25] In 1927 Bandera joined Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO).[25] In February 1929 he joined Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN).[26] Bandera was drawn into national activity by Stepan Okhrymovych, one of the leaders of the Ukrainian youth movement.[23] During his studies, he devoted his efforts to underground and nationalist activities, for which he was arrested several times. The first time was on 14 November 1928, for illegally celebrating the 10th anniversary of the ZUNR;[26] in 1930 with his brother Andrii;[26] and in 1932-33 as many as six times. Between March and June 1932, he spent three months in prison in connection with the investigation of the assassination of Emilian Czechowski by Iurii Berezynskyi.[26] In the early 1930s, in response to attacks perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists, Polish authorities carried out the pacification of Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia against the Ukrainian minority. This resulted in destroyed property and mass detentions, and took place in southeastern voivodeships of the Second Polish Republic.[27] Organisation of Ukrainian NationalistsBandera joined OUN in 1929, and quickly climbed through the ranks, thanks to the support of Okhrymovych, becoming in 1930 the head of a section distributing OUN propaganda in Eastern Galicia.[28] A year later, he became director of propaganda for the whole OUN.[28] After Okhrymovych's death and the flight from Poland of his successor Ivan Habrusevych in 1931, he became the leading candidate to become head of the homeland executive.[28] But due to the fact that he was in detention at the time, he was unable to assume this function, and upon his release he became deputy to Bohdan Kordiuk, who assumed this function.[28] After the failure of the attack on the post office in Gródek Jagielloński, Kordiuk had to step down and Bandera took over de facto his function, which was sanctioned at a conference in Berlin on 3–6 June 1933.[28] On 29 August 1931, Polish politician Tadeusz Hołówko was assassinated by two members of the OUN Vasyl Bilas and Dmytro Danylyshyn.[29] Both were sentenced to death. Bandera-led OUN propaganda made them martyrs and ordered Ukrainian priests in Lviv and elsewhere to ring bells on the day of their execution.[29] Since 1932 Bandera was assistant chief of OUN and around that time controlled several "warrior units" in Poland in places such as the Free City of Danzig (Wolne Miasto Gdańsk), Drohobycz, Lwów, Stanisławów, Brzezany, and Truskawiec. Bandera collaborated closely with Richard Yary, who would later side with Bandera and help him form OUN-B.[citation needed] On Bandera's orders OUN began a campaign of terrorist acts, such as attacks on post-offices, bomb-throwing at Polish exhibitions and murders of policemen[30] to mass campaigns against Polish tobacco and alcohol monopolies and against the denationalization of Ukrainian youth.[citation needed] In 1934 Bandera was arrested in Lwów and tried twice: first, concerning involvement in a plot to assassinate the minister of internal affairs, Bronisław Pieracki, and second at a general trial of OUN executives. He was convicted of terrorism and sentenced to death. The death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.[31]  After the trials, Bandera became renowned and admired among Ukrainians in Poland and abroad[citation needed] as a symbol of a revolutionary who fought for Ukrainian independence.[32] While in prison Bandera was "to some extent detached from OUN discourses" but not completely isolated from the global political debates of the late 1930s thanks to Ukrainian and other newspaper subscriptions delivered to his cell.[33] World War IIBefore World War II the territory of today's Ukraine was split between Poland, the Soviet Union, Romania and Czechoslovakia. Prior to the 1939 invasion of Poland, German military intelligence recruited OUN members into the Bergbauernhilfe unit and smuggled Ukrainian nationalists into Poland in order to erode Polish defences by conducting a terror campaign directed at Polish farmers and Jews. OUN leaders Andriy Melnyk (code name Consul I) and Bandera (code name Consul II) both served as agents of the Nazi Germany military intelligence Abwehr Second Department.[34][35][34] Their goal was to run diversion activities after Germany's attack on the Soviet Union. This information is part of the testimony that Abwehr Colonel Erwin Stolze gave on 25 December 1945 and submitted to the Nuremberg trials, with a request to be admitted as evidence.[34][36][37][38] Bandera was freed from Brest (Brześć) Prison in Eastern Poland in early September 1939, as a result of the invasion of Poland. There are differing accounts of the circumstances of his release.[nb 1] Soon thereafter Eastern Poland was occupied by the Soviet Union. Upon release from prison, Bandera moved first to Lviv, but after realising it would be occupied by the Soviets, Bandera together with other OUN members, moved to Kraków, the capital of Germany's occupational General Government.[47] where, according to Tadeusz Piotrowski, he established close connections with the German Abwehr and Wehrmacht.[48][49] There, he also came in contact with the leader of the OUN, Andriy Atanasovych Melnyk. In 1940, the political differences and expectations between the two leaders caused the OUN to split into two factions, OUN-B and OUN-M (Banderites and Melnykites) each one claiming legitimacy.[50] The factions differed in ideology, strategy and tactics:[51] the OUN-M faction led by Melnyk preached a more conservative approach to nation-building, while the OUN-B faction, led by Bandera, supported a revolutionary approach; however, both factions exhibited similar levels of radical nationalism, fascism, antisemitism, xenophobia and violence.[14][52][53] The vast majority of young OUN members joined Bandera's faction. OUN-B was devoted to the independence of Ukraine, as a single-party fascist totalitarian state free of national minorities.[54][nb 2][59] It was later implicated in the Holocaust.[12][nb 3][60][61][62][63][64][14] Before the independence proclamation of 30 June 1941, Bandera oversaw the formation of so-called "Mobile Groups" (Ukrainian: мобільні групи), which were small (5–15 members) groups of OUN-B members who would travel from General Government to Western Ukraine and, after a German advance to Eastern Ukraine, encourage support for the OUN-B and establish local authorities run by OUN-B activists.[65] In total, approximately 7,000 people participated in these mobile groups, and they found followers among a wide circle of intellectuals, such as Ivan Bahriany, Vasyl Barka, Hryhorii Vashchenko and many others.[citation needed]  In spring 1941, Bandera held meetings with the heads of Germany's intelligence, regarding the formation of "Nachtigall" and "Roland" Battalions. In the spring of that year, the OUN received 2.5 million marks for subversive activities inside the Soviet Union.[65][66] Gestapo and Abwehr officials protected Bandera's followers, as both organizations intended to use them for their own purposes.[67] On 30 June 1941, with the arrival of Nazi troops in Ukraine, the OUN-B unilaterally declared an independent Ukrainian state ("Act of Renewal of Ukrainian Statehood").[68][69] The proclamation pledged a cooperation of the new Ukrainian state with Nazi Germany under the leadership of Hitler.[5] The declaration was accompanied by violent pogroms.[68][52] Bandera did not actively support or participate in the Lviv pogroms or acts of violence against Jewish and Polish civilians, but was well informed about the violence and was "unable or unwilling to instruct Ukrainian nationalist military troops (as Nachtigall, Roland and UPA) to protect vulnerable minorities under their control". As German historian Olaf Glöckner writes, Bandera "failed to manage this problem (ethnic and anti-Semitic hatred) inside his forces, just like Symon Petljura failed 25 years before him."[70] OUN(b) leaders' expectation that the Nazi regime would post-factum recognize an independent fascist Ukraine as an Axis ally proved to be wrong.[68] German authorities requested the declaration be withdrawn, Stetsko and Bandera refused.[71] The Germans barred Bandera from moving to newly conquered Lviv, limiting his residency to occupied Kraków.[72] On 5 July, Bandera was brought to Berlin, where he was placed in honorable captivity.[73][74] On 12 July, the prime minister of the newly formed Ukrainian National Government, Yaroslav Stetsko, was arrested and taken to Berlin. Although released from custody on 14 July, both were required to stay in Berlin. Bandera was free to move around the city, but could not leave it.[73] The Germans closed OUN-B offices in Berlin and Vienna,[75] and on 15 September 1941 Bandera and leading OUN members were arrested by the Gestapo.[76] By the end of 1941 relations between Nazi Germany and the OUN-B had soured to the point where a Nazi document dated 25 November 1941 stated that "the Bandera Movement is preparing a revolt in the Reichskommissariat which has as its ultimate aim the establishment of an independent Ukraine. All functionaries of the Bandera Movement must be arrested at once and, after thorough interrogation, are to be liquidated".[77] In January 1942, Bandera was transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp's special prison cell building (Zellenbau) for high-profile political prisoners such as Horia Sima, the chancellor of Austria, Kurt Schuschnigg or Stefan Grot-Rowecki[78]: 212 and high risk escapees.[79] Bandera was not completely cut off from the outside world; his wife visited him regularly and was able to help him keep in touch with his followers.[80] In April 1944, Bandera and his deputy Yaroslav Stetsko were approached by a Reich Security Main Office official to discuss plans for diversions and sabotage against the Soviet Army.[81] Bandera's release was preceded by lengthy talks between the Germans and the UPA in Galicia and Volhynia. Local talks and agreements took place as early as the end of 1943, talks at the central level of the OUN-B began in March 1944 and ended with the conclusion of an informal agreement in August or September 1944.[82] The talks from the OUN-B Provid side were led mainly by Ivan Hrynokh.[83] Meanwhile, in July 1944, the formation of the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR) took place, which was intended as a supra-party organization that constituted the civilian body overseeing the UPA and was intended as the supreme authority in Ukraine. In reality, only members or sympathizers of the OUN-B took part in its formation.[84] Kyrylo Osmak became president of the UHVR, but real power rested in the hands of the General Secretariat, headed by Roman Shukhevych.[85] At the congress, decisions were made to stop any open collaboration with the Germans, creating a government alongside them was excluded, only taking supplies from them was considered. It was planned to carry out partisan fighting in the rear of the approaching Soviet army. A decision was also taken to move away from radically nationalist rhetoric towards greater democratisation.[84] A UHVR foreign mission led by Mykola Lebed was sent to establish contact with Western governments.[86] On 28 September 1944,[80] Bandera was released by the German authorities and moved to house arrest. Shortly after, the Germans released some 300 OUN members, including Stetsko and Melnyk.[80] The release of OUN members was one of the few successes of Lebed's mission on behalf of the UHVR, which failed to establish contacts with the Western Allies.[87] Bandera reacted negatively to the changes taking place within the OUN-B in Ukraine. His opposition was provoked by the 'democratisation' of the OUN-B and, above all, the relegation of the former leadership of the organisation to purely symbolic roles.[87] On 5 October 1944, SS-Obergruppenführer Gottlob Berger met with Bandera and offered him the opportunity to join Andrey Vlasov and his Russian Liberation Army, which Bandera rejected.[88] In December 1944, the Abwehr moved Bandera and Stetsko to Kraków in order to prepare the Ukrainian unit to be parachuted to the rear of the Soviet army.[89] From there they sent Yurii Lopatynskyi as a courier to Shukhevych.[89][90] Bandera informed him that he was ready to return to Ukraine, while Stetsko informed him that he still considered himself the Ukrainian prime minister.[89][91] Lopatynskyi arrived to Shukhevych in early January 1945. At a meeting of the Provid on 5 and 6 February 1945, it was decided that Bandera's return to Ukraine was pointless, and that it might be more beneficial for him to remain in the West, where, as a former Nazi prisoner, he could organize support of international opinion.[92] Bandera was re-elected as leader of the whole OUN. Roman Shukhevych resigned as the leader of the OUN and became the leader of OUN in Ukraine and Bandera's deputy.[93][94] The leaders of the OUN in Ukraine also came to the conclusion that the German-Soviet war would soon end in a Soviet victory, and a decision was made to continue the fight against the Soviets with smaller units, in order to maintain the will to fight among the population. It was also decided to hold talks with the Polish underground to conclude an anti-Soviet alliance.[94] At that point the cooperation with Germans basically ceased with the loss of direct contact and the front moving further west.[95] In January, Bandera was in Lehnin, west of Berlin. Later he went to Weimar, where he took part in the formation of the Ukrainian National Committee (UNK) as one of the leaders alongside Pavlo Shandruk, Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Andriy Melnyk, Oleksandr Semenko and Pavlo Skoropadsky.[96] In March, the UNK appointed Shandrukh as commander of the newly formed Ukrainian National Army (UNA), which was to fight the Soviets alongside the Germans; the Waffen-SS Galizien division was incorporated.[96][87] Bandera later denied in conversations with the CIA that he had been involved in the formation of these organisations or any collaboration with Germany after his release.[93] In February 1945, at a conference of the OUN-B in Vienna, Bandera was made the leader of the Foreign Units of the OUN (ZCh OUN).[93] It was there that he openly criticised for the first time the changes that had taken place in the OUN-B in Ukraine.[87] With the Red Army approaching, Bandera left Vienna and travelled to Innsbruck via Prague.[93] Postwar activity After the war, Bandera and his family moved several times around West Germany, staying close to and in Munich, where Bandera organized the ZCh OUN center. He used false identification documents that helped him to conceal his past relationship with the Nazis.[97] On 16 April 1946, the Yaroslav Stetsko-led Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations was founded, with which Bandera also collaborated.[98] The ZCh OUN quickly became the largest organisation in the approximately 110,000-strong Ukrainian diaspora in Germany, with 5,000 members.[99] Part of the organisation was the SB security service, headed by Myron Matviyenko.[98] The OUN-M was three times smaller. The foreign representation of the UHVR (ZP UHVR), led by Mykola Lebed, operated separately from the ZCh OUN, but many of its members belonged to both organizations.[98] As early as 1945, ZCh had established contacts with Western intelligence; from 1948 onwards, it was permanent cooperation with British intelligence, which helped to transfer couriers to Ukraine in return for receiving intelligence data.[100][101] ZP UHVR, collaborated with the US intelligence.[98] A September 1945 report by the US Office of Strategic Services said that Bandera had "earned a fierce reputation for conducting a 'reign of terror' during World War II".[102]: 27 Bandera was protected by the US-backed Gehlen Organization but he also received help from underground organizations of former Nazis who helped Bandera to cross borders between Allied occupation zones.[103] In 1946, agents of the US Army intelligence agency Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) and NKVD entered into extradition negotiations based on the intra-Allied cooperation wartime agreement made at the Yalta Conference. The CIC wanted Frederick Wilhelm Kaltenbach, who would turn out to be deceased, and in return the Soviet Union proposed Bandera. Bandera and many Ukrainian nationalists had ended up in the American zone after the war. The Soviet Union regarded all Ukrainians as Soviet citizens and demanded their repatriation under the intra-Alied agreement. The US thought Bandera was too valuable to give up due to his knowledge of the Soviet Union, so the US started blocking his extradition under an operation called "Anyface". From the perspective of the US, the Soviet Union and Poland were issuing extradition attempts of these Ukrainians to prevent the US from getting sources of intelligence, so this became one of the factors in the breakdown of the cooperation agreement.[104] However, the CIC still considered Bandera untrustworthy and were concerned about the impact of his activities on Soviet-American relations, and in mid-1947 conducted an extensive and aggressive search to locate him.[43]: 80 It failed, having described their quarry as "extremely dangerous" and "constantly en route, frequently in disguise".[43]: 79 Some American intelligence reported that he even was guarded by former SS men.[105] The Bavarian state government initiated a crackdown on Bandera's organization for crimes such as counterfeiting and kidnapping. Gerhard von Mende, a West German government official, provided protection to Bandera who in turn provided him with political reports, which were relayed to the West German Foreign Office. Bandera reached an agreement with the BND, offering them his service, despite the CIA warning the West Germans against cooperating with him.[43]: 83–84 Following the war Bandera also visited Ukrainian communities in Canada, Austria, Italy, Spain, Belgium, UK and Holland.[106] Death The MGB, and from 1954, the Soviet KGB, multiple times attempted to kidnap or assassinate Bandera.[107] On 15 October 1959, Bandera collapsed outside of Kreittmayrstrasse 7 in Munich and died shortly thereafter. A medical examination established that the cause of his death was poisoning by cyanide gas.[108][109] On 20 October 1959, Bandera was buried in the Waldfriedhof (lit. 'woodland cemetery') in Munich.[110] His wife and three children moved to Toronto, Canada.[111] Two years after his death, on 17 November 1961, the German judicial bodies announced that Bandera's murderer had been a KGB agent named Bohdan Stashynsky who used a cyanide dust spraying gun to murder Bandera acting on the orders of Soviet KGB head Alexander Shelepin and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev.[43][112] After a detailed investigation against Stashynsky, who by then had defected from the KGB and confessed the killing, a trial took place from 8 to 15 October 1962. Stashynsky was convicted, and on 19 October he was sentenced to eight years in prison; he was released after four years. Stashynsky had earlier assassinated Bandera's associate Lev Rebet by similar means.[113] FamilyBandera's brothers, Oleksandr and Vasyl, were arrested by the Germans and sent to Auschwitz concentration camp where they were allegedly killed by Polish inmates in 1942.[114][verification needed] His father Andriy was arrested by the Soviets in late May 1941 for harboring an OUN member and transferred to Kyiv. On 8 July he was sentenced to death and executed on the 10th. His sisters Oksana and Marta–Maria were arrested by the NKVD in 1941 and sent to a gulag in Siberia. Both were released in 1960 without the right to return to Ukraine. Marta–Maria died in Siberia in 1982, and Oksana returned to Ukraine in 1989 where she died in 2004. Another sister, Volodymyra, was sentenced to a term in Soviet labor camps from 1946 to 1956. She returned to Ukraine in 1956.[115] Views According to historian Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, "Bandera's worldview was shaped by numerous far-right values and concepts including ultranationalism, fascism, racism, and antisemitism; by fascination with violence; by the belief that only war could establish a Ukrainian state; and by hostility to democracy, communism, and socialism. Like other young Ukrainian nationalists, he combined extremism with religion and used religion to sacralize politics and violence."[116] Historian Timothy Snyder described Bandera as a fascist who "aimed to make of Ukraine a one-party fascist dictatorship without national minorities".[54][nb 4] Historian John-Paul Himka writes that Bandera remained true to the fascist ideology to the end.[52] Ukrainian historian Andrii Portnov writes that Bandera remained a proponent of authoritarian and violent politics until his death.[117] Historian Per Anders Rudling said that Bandera and his followers "advocated the selective breeding to create a 'pure' Ukrainian race",[13] and that "the OUN shared the fascist attributes of anti-liberalism, anti-conservatism, and anti-communism, an armed party, totalitarianism, antisemitism, Führerprinzip, and adoption of fascist greetings. Its leaders eagerly emphasized to Hitler and Ribbentrop that they shared the Nazi Weltanschauung and a commitment to a fascist New Europe."[118] Historian David R. Marples described Bandera's views as "not untypical of his generation" but as holding "an extreme political stance that rejected any form of cooperation with the rulers of Ukrainian territories: the Poles and the Soviet authorities". Marples also described Bandera as "neither an orator nor a theoretician", and wrote that he had minimal importance as a thinker.[119] Marples considered Rossolinski-Liebe to place too much importance on Bandera's views, writing that Rossolinski-Liebe struggled to find anything of note written by Bandera, and had assumed he was influenced by OUN publicist Dmytro Dontsov and OUN journals.[120] Historian Taras Hunczak argues that Bandera's central article of faith was Ukrainian statehood, and any other goal was secondary to this view. Through an analysis of OUN documents Hunczak demonstrates the consistent expressed goal of an independent Ukrainian state through the whole history, while the OUN's stance towards the German Nazi government was changing, shifting from initial support, towards rejection, as OUN leaders become disillusioned seeing Nazi Germany rejection of Ukrainian independence. The OUN memorandum from 23 June 1941 notes that "German troops entering Ukraine will be, of course, greeted at first as liberators, but this attitude can soon change, in case Germany comes into Ukraine without appropriate promises of [its] goal to reestablish the Ukrainian state." The OUN memorandum from 14 August declares the OUN wish "to work together with Germany not from opportunism, but from a realization of the need of such cooperation for the well-being of Ukraine". Hunczak observes OUN leaders', including Bandera, attitude change after 15 September 1942, following Gestapo's killing of an OUN member, prompting the OUN to use the rhetoric of "German occupier" in reference to Nazi regime.[121] Political scientist Andreas Umland opposes characterizing Bandera as a "Nazi", and characterizes Bandera as a "Ukrainian ultranationalist", commenting that Ukrainian nationalism was "not a copy of Nazism".[10] Political scientist Luboš Veselý criticises Rossoliński-Liebe's book on Bandera as intentionally painting him and all Ukrainian nationalists negatively. Per Veselý, Rossoliński-Liebe "considers nationalism in general to be closely related to fascism" and fails to put Ukrainian nationalism, as well as antisemitism and fascist movements, in context of their rise in other European countries at the time. The book does not mention arguments of other renowned Ukrainian historians, such as Heorhii Kasianov. Veselý says that "Bandera was against closer cooperation with the Nazis and he insisted that the Ukrainian national movement should not be dependent on anyone", thus opposing Rossoliński-Liebe's conclusion that Ukrainian nationalists needed the protection of Nazi Germany and therefore collaborated with them. Veselý concludes that all of this makes Rossoliński-Liebe's assessment of Bandera as a "condemnable symbol of Ukrainian fascism, antisemitism, terrorism and an inspiration for anti-Jewish pogroms and even genocide" "an abusive oversimplification, uprooting events and people from the context of the era or using harsh, unfounded and emotional judgments."[122] Ukrainian historian Oleksandr Zaitsev notes that Rossolinski-Liebe's approach ignores "the fundamental differences between ultra-nationalist movements of nations with and without a state". Zaitsev highlights that the OUN did not identify itself with fascism, but "officially objected to this identification". Zaitsev suggests that it would be more correct to see the OUN and Bandera as the revolutionary ultranationalist movements of stateless nations, which were aiming not on "the reorganization of the existing state according to totalitarian principles, but to create a new state, using all available means, including terror, to this end." According to Zaitsev, Rossolinski-Liebe omits some facts, which do not fit into his "a priori scheme of 'fascism', 'racism' and 'genocidal nationalism'", and denies "the presence of liberatory and democratic elements" in Bandera movement.[123] Historian Dr Raul Cârstocea, too, finds Rossoliński-Liebe's association of Bandera with fascism problematic, for one of the reasons Rossoliński-Liebe's used definition of fascism being too wide.[124] Views towards PolesMarples says that Bandera "regarded Russia as the principal enemy of Ukraine, and showed little tolerance for the other two groups inhabiting Ukrainian ethnic territories, Poles and Jews".[119] In late 1942, when Bandera was in a German concentration camp, his organization, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, was involved in a massacre of Poles in Volhynia. In early 1944, ethnic cleansing also spread to Eastern Galicia. It is estimated that more than 35,000 and up to 60,000 Poles, mostly women and children along with unarmed men, were killed during the spring and summer campaign of 1943 in Volhynia, and up to 133,000 if other regions, such as Eastern Galicia, are included.[125][126][127] Despite the central role played by Bandera's followers in the massacre of Poles in western Ukraine, Bandera himself was interned in a German concentration camp when the concrete decision to massacre the Poles was made and when the Poles were killed.[clarification needed] According to Yaroslav Hrytsak, Bandera was not completely aware of events in Ukraine during his internment from the summer of 1941 and had serious differences of opinion with Mykola Lebed, the OUN-B leader who remained in Ukraine and who was one of the chief architects of the massacres of Poles.[128][129] Views towards JewsBandera held the antisemitic views typical of his generation.[130][119] Speaking about Bandera and his men, political scientist Alexander John Motyl told Tablet that antisemitism was not a core part of Ukrainian nationalism in the way it was for Nazism, and the Soviet Union and Poland were considered to be the primary enemies of the OUN. According to him, the attitude of the Ukrainian nationalists towards Jews depended on political circumstances, and they considered Jews to be a "problem" because they were "implicated, or believed to be implicated" in aiding the Soviets in taking Ukrainian territory, as well as not being Ukrainian.[131] Norman Goda wrote that "Historian Karel Berkhoff, among others, has shown that Bandera, his deputies, and the Nazis shared a key obsession, namely the notion that the Jews in Ukraine were behind Communism and Stalinist imperialism and must be destroyed."[12] On 10 August 1940, Bandera wrote a letter to Andriy Melnyk saying that he would accept Melnyk's leadership of the OUN, provided he expelled "traitors" in the leadership. One of these was Mykola Stsibors'kyi, who Bandera accused of an absence of "morality and ethics in family life" due to having married a Jewish woman, and especially, a "suspicious" Russian Jewish woman.[132] Portnov argues that "Bandera did not participate personally in the underground war conducted by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which included the organized ethnic cleansing of the Polish population of Volhynia in north-western Ukraine and killings of the Jews, but he also never condemned them."[117] Similarly, Rossolinski-Liebe and Umland both observe that Bandera personally had no part in the murders of Jews. Rossolinski-Liebe said "he had found no evidence that Bandera supported or condemned 'ethnic cleansing' or killing Jews and other minorities. It was, however, important that people from OUN and UPA 'identified with him.'"[10] However, Bandera was aware of at least some of his followers' anti-Jewish violence: In June 1941, Yaroslav Stetsko sent Bandera a report in which he stated "We are creating a militia which will help to remove the Jews and protect the population."[133][134] According to Rossoliński-Liebe, "After the Second World War and the Holocaust, both Bandera and his admirers were embarrassed by the vehement antisemitic component of their interwar political views and denied it systematically."[130] Legacy  In his 2006 article discussing "the reinterpretations of [Bandera's] career", historian David R. Marples, who specialises in the history of this area of Eastern Europe, stated that "the impact of Bandera lies less in his own political life and beliefs than in the events enacted in his name, or the conflicts that arose between his supporters and their enemies."[135] According to The Guardian, "Post-war Soviet history propagated the image of Bandera and the UPA as exclusively fascist collaborators and xenophobes."[136] On the other hand, with the rise of nationalism in Ukraine, his memory there has been elevated. The glorification and attempts to rehabilitate Bandera are growing trends in Ukraine.[137] CommemorationNeither Bandera nor OUN have been used as national symbols by the current Ukrainian government. Ukrainian president Zelensky has not presented Bandera or his associates as national heroes. Nevertheless, the memory of Bandera can be found in Ukraine.[138]  In late 2006, the Lviv city administration announced the future transference of the tombs of Stepan Bandera, Andriy Melnyk, Yevhen Konovalets and other key leaders of OUN/UPA to a new area of Lychakiv Cemetery specifically dedicated to victims of the repressions of the Ukrainian national liberation struggle.[139] In October 2007, the city of Lviv erected a statue dedicated to Bandera.[140] The appearance of the statue has engendered a far-reaching debate about the role of Stepan Bandera and UPA in Ukrainian history. The two previously erected statues were blown up by unknown perpetrators; the current is guarded by a militia detachment 24/7.[when?] On 18 October 2007, the Lviv City Council adopted a resolution establishing the Award of Stepan Bandera in journalism.[141][142] On 1 January 2009, his 100th birthday was celebrated in several Ukrainian centres[143][144][145][146][147] and a postage stamp with his portrait was issued the same day.[148] On 1 January 2014, Bandera's 105th birthday was celebrated by a torchlight procession of 15,000 people in the centre of Kyiv and thousands more rallied near his statue in Lviv.[149][150][151] The march was supported by the far-right Svoboda party and some members of the center-right Batkivshchyna.[152] In 2018, the Ukrainian Parliament voted to include Bandera's 110th birthday, on 1 January 2019, in a list of memorable dates and anniversaries to be celebrated that year.[153][154][155] The decision was criticized by the Jewish organization Simon Wiesenthal Center.[156] There are Stepan Bandera museums in Dubliany, Volia-Zaderevatska, Staryi Uhryniv, and Yahilnytsia. There is a Stepan Bandera Museum of Liberation Struggle in London, part of the OUN Archive,[157] and The Bandera Family Museum (Музей родини Бандерів) in Stryi.[158][159] There are also Stepan Bandera streets in Lviv (formerly vulytsia Myru, "Peace street"), Lutsk (formerly Suvorovska street), Rivne (formerly Moskovska street), Kolomyia, Ivano-Frankivsk, Chervonohrad (formerly Nad Buhom street),[160] Berezhany (formerly Cherniakhovskoho street), Drohobych (formerly Sliusarska street), Stryi, Kalush, Kovel, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Horodenka, Dubrovytsia, Kolomyia, Dolyna, Iziaslav, Skole, Shepetivka, Brovary, and Boryspil, and a Stepan Bandera Avenue in Ternopil (part of the former Lenin Avenue).[161] On 16 January 2017, the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance stated that of the 51,493 streets, squares and "other facilities" that had been renamed (since 2015) due to decommunization 34 streets were named after Stepan Bandera.[162] Due to "association with the communist totalitarian regime", the Kyiv City Council on 7 July 2016 voted 87 to 10 in favor of supporting renaming Moscow Avenue to Stepan Bandera Avenue.[163][164] In Dnipro, the local Jewish community opposed renaming a street after Bandera, but after the start of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, they changed their stance and the street was renamed in September 2022;[165][166] this street had originally been the Gymnasium Street until it was renamed to Otto Schmidt Street by Soviet authorities in 1934.[167] In December 2022, the recently liberated city of Izium decided to rename Pushkin Street to Stepana Bandera Street.[168] After the fall of the Soviet Union, monuments dedicated to Stepan Bandera have been constructed in a number of western Ukrainian cities and villages, including a statue in Lviv.[169] Bandera was also named an honorary citizen of a number of western Ukrainian cities.[citation needed] In late 2018, the Lviv Oblast Council decided to declare the year of 2019 to be the year of Stepan Bandera, sparking protests by Israel.[170][171] In 2021, the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory under the authority of the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture, included Bandera, among other Ukrainian nationalist figures, in Virtual Necropolis, a project intended to commemorate historical figures important for Ukraine.[172] Two feature films have been made about Bandera, Assassination: An October Murder in Munich (1995) and The Undefeated (2000), both directed by Oles Yanchuk, along with a number of documentary films.[citation needed] Hero of Ukraine award On 22 January 2010, on the Day of Unity of Ukraine, the then-president of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko awarded to Bandera the title of Hero of Ukraine (posthumously) for "defending national ideas and battling for an independent Ukrainian state".[173][174][175][176] Interfax-Ukraine reported that a grandson of Bandera, also named Stepan, accepted the award that day from the Ukrainian President during the state ceremony to commemorate the Day of Unity of Ukraine at the National Opera House of Ukraine.[174] Ukraine's "intellectuals with nationalist leanings" supported the designation, but liberals disapproved it. For them, Bandera "was too controversial", and was not uniting people but dividing them. They were opposing Bandera's radical nationalism and OUN's leadership xenophoby and antisemitism. The designation let the pro-Russian politicians "to claim that the Orange camp had pro-Nazi sympathies". The move alienated the Polish allies, who are the main supporters of Ukraine joining the EU.[177] The European Parliament condemned the award, as did Russia, Poland, and Jewish politicians and organizations, such as the Simon Wiesenthal Center.[178][179][180][181][182] On 25 February 2010, the European Parliament expressed hope the decision would be reconsidered.[183] On 14 May 2010, the Russian Foreign Ministry said "the event is so odious that it could no doubt cause a negative reaction in the first place in Ukraine. Already it is known a position on this issue of a number of Ukrainian politicians, who believe that solutions of this kind do not contribute to the consolidation of Ukrainian public opinion."[184] On the other hand, the decree was applauded by Ukrainian nationalists in western Ukraine.[185][186] After the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election, the succeeding president Viktor Yanukovych declared the award illegal, since Bandera was never a citizen of Ukraine, a stipulation necessary for getting the award. On 5 March 2010, Yanukovych stated that he would make a decision to repeal the decrees to honor the title of Heroes of Ukraine to Bandera and fellow nationalist Roman Shukhevych before the next Victory Day,[187] although the Hero of Ukraine decrees do not stipulate the possibility that a decree on awarding this title can be annulled.[188] On 2 April 2010, an administrative Donetsk region court ruled the presidential decree awarding the title to be illegal. According to the court's decision, Bandera was not a citizen of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (vis-à-vis Ukraine).[189][190][191][192] On 5 April 2010, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine refused to start constitutional proceedings on the constitutionality of the Yushchenko decree the award was based on. A ruling by the court was submitted by the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea on 20 January 2010.[193] In January 2011, under Yanukovych's government, the presidential press service informed that the award was officially annulled.[194][195] This was done after a cassation appeal filed against the ruling by Donetsk District Administrative Court was rejected by the Higher Administrative Court of Ukraine on 12 January 2011.[196][197][198] Former president Yushchenko called the annulment "a gross error".[199] In December 2018, the Ukrainian parliament considered a motion to again confer the award on Bandera; the proposal was rejected in August 2019.[200] 2014 Russian intervention in Ukraine During the 2014 Crimean crisis and unrest in Ukraine, pro-Russian Ukrainians, Russians (in Russia), and some Western authors alluded to the bad influence of Bandera on Euromaidan protesters and pro-Ukrainian Unity supporters in justifying their actions.[201] According to The Guardian, "The term 'Banderite' to describe his followers gained a recent new and malign life when Russian media used it to demonise Maidan protesters in Kiev, telling people in Crimea and east Ukraine that gangs of Banderites were coming to carry out ethnic cleansing of Russians."[136] Russian media used this to justify Russia's actions.[13] Putin welcomed the annexation of Crimea by declaring that he "was saving them from the new Ukrainian leaders who are the ideological heirs of Bandera, Hitler's accomplice during World War II."[13] Pro-Russian activists claimed: "Those people in Kyiv are Bandera-following Nazi collaborators."[13] Ukrainians in Russia complained of being labelled "Banderites", even if they were from parts of Ukraine where Bandera is negatively remembered.[13] A minority of people supporting Bandera views was presented in the Euromaidan protests, but Russian propaganda exaggerated their presence and demonized all Maidan protestors.[13][202][203] Russian media even labeled "banderites" those 30,000 Russians who went to protest against Russian aggression in Ukraine on the Moscow March of Peace.[203] Russian invasion of UkraineDuring his invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin made references to "Banderites" in his speeches and spoke of an inevitable confrontation with "neo-Nazis, Banderites" in his Victory Day speech.[10][204] Russia heavily promoted the theme of "denazification", and used rhetoric that was similar to Soviet era policy of equating the development of Ukrainian national identity with Nazism due to Bandera's collaboration, which has a particular resonance in Russia.[205] The Washington Post reported on Russian soldiers rounding up villagers who were deemed to be "Nazis" or "Banderites".[206] Deutsche Welle reported that media in Ukraine included many eyewitness accounts of Russian soldiers pursuing Bandera supporters, and wrote that "whoever is deemed to be a supporter faces torture or death".[10] Attitudes in Ukraine towards Bandera A poll conducted in early May 2021 by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation together with the Razumkov Centre's sociological service showed that 32% of citizens considered Bandera's activity as a historical figure to be positive for Ukraine, as many considered his activity negative; another 21% consider Bandera's activities as positive as they are negative. According to the poll, a positive attitude prevailed in the western region of Ukraine (70%); in the central region of the state, 27% of respondents consider his activity positive, 27% consider his activity negative and 27% consider his activity both positive and negative; negative attitude prevails in the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine (54% and 48% of respondents consider his activity negative for Ukraine, respectively).[207]  Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Bandera's favorability appeared to shoot up rapidly, with 74% of Ukrainians viewing him favorably according to an April 2022 poll from a Ukrainian research organization. Bandera continued to cause friction with countries such as Poland and Israel.[10] Historian Vyacheslav Likhachev told Haaretz that, for public consciousness in Ukraine, the only important thing about Bandera was that he fought for Ukrainian independence, and that other details are not important, especially in the context of events from 2014 onwards, where the struggle for Ukrainian independence became more prominent.[208] See alsoNotes

References

Bibliography

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||