|

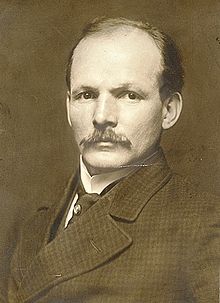

Solon Borglum

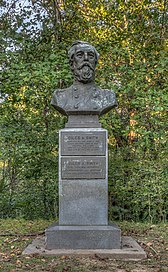

Solon Hannibal de la Mothe Borglum (December 22, 1868 – January 31, 1922)[1] was an American sculptor. He is most noted for his depiction of frontier life, and especially his experience with cowboys and native Americans. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre by France[2] for his work with Les Foyers du Soldat service clubs during World War I.[3] Early lifeBorn in Ogden, Utah, Borglum was the younger brother of Gutzon Borglum and uncle of Lincoln Borglum, the two men most responsible for the creation of the carvings at Mount Rushmore. Solon's Danish immigrant father James Borglum was a Mormon polygamist, being married to two sisters, Ida and Christina Mikkelsen. When the family – each wife had two children – moved to Nebraska they could no longer openly be husband and wives, so Solon and Gutzon's mother Christina was listed as the family servant. When the father moved the family again to St. Louis in 1871, so that he could attend medical school, the decision was made to leave Christina behind. The children were told to never talk about her again. Solon was about three years old at the time.[4] Solon grew up in Fremont, Nebraska and Omaha[5] and spent his early years as a rancher in western Nebraska.[6] Solon’s father was a physician but had worked as a wood-carver, which almost certainly influenced Solon’s older brother, Gutzon, to pursue a career as an artist. Having shown little interest in formal schooling, the younger son spent his teens working on his father’s ranch near Fremont, Nebraska. He showed a talent for drawing horses, and his careful studies of their movements prompted Gutzon to encourage Solon to pursue art as a profession. EducationIn 1893 Solon went to Omaha to study with J. Laurie Wallace, a former pupil of Thomas Eakins. Following this early, and evidently brief, formal training, he joined his brother Gutzon at his home in the Sierra Madre mountains. A personality clash with Gutzon’s first wife Lisa however, forced Solon to move on; he went to Los Angeles, where he painted portraits and to Santa Ana, California, where he taught art privately. He had little success, however, and in November 1895 he traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he entered the Cincinnati Art Academy. One of his instructors, the sculptor Louis Rebisso, encouraged him to try sculpting. His first effort was a sculpture of a group of horses based on observations and drawings he had made at the U.S. Mail stables in Cincinnati.[7]  In 1898 the Art Academy awarded Borglum a scholarship that allowed him to go to Paris, where he matriculated at the Académie Julian as a student of Denys Puech. He met leading sculptors Emmanuel Fremiet and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who gave him further encouragement. Borglum received a silver medal at the Exposition Universelle (1900) and another at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, NY[8] Later lifeIn 1898, Borglum married, and Solon and his wife, Emma (née Vignal),[9] spent the summer of 1899 at the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota. Though he later lived in Paris and New York City and achieved a reputation as one of America's notable sculptors, it was his depictions of frontier life, and especially his experience with cowboys and Native American peoples, which was the basis of his reputation.[10] In 1901, Solon and his wife, Emma had a son, Paul Arnold Borglum.[11][12] On 9 December 1903, Solon and his wife, Emma had a daughter, Monica (née Borglum) Davies.[13][14] In 1906, Borglum moved to the Silvermine neighborhood of New Canaan, Connecticut, where he helped found the "Knockers Club" of artists. His brother, Gutzon, lived in nearby Stamford, Connecticut from 1910 to 1920.[15] In 1911, Borglum was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member.[16] During World War I, Borglum was in France, serving as secretary of the YMCA, and then taught sculpture at the American Expeditionary Forces Art Training Center in Bellevue (Hauts-de-Seine), Seine-et-Oise,[17] outside Paris.[18] Circa 1918, in New York City, he opened a second[19] studio[20] and established the American School of Sculpture.[21] He ran the school and gave many lectures on art until his death after an appendectomy complicated by his war wounds[22] in January 1922.[23] His legacy was carried on by his wife Emma until her death in 1934, at which point his daughter Monica and her husband, A. Mervyn Davies,[24] oversaw the exhibition of his artwork. In 1974 they published his biography Solon H. Borglum: A Man Who Stands Alone. Borglum's papers are held at the Archives of American Art,[25] and the Library of Congress.[26] WorksBorglum created several animal groups while in Paris, including Lassoing Wild Horses and The Stampede of Wild Horses, which were shown at the Paris Salon in 1898 and 1899, respectively. The year 1903 was a banner one for the artist. He had a one-man show of thirty-two small sculptures at the Keppel Gallery, New York. In his ground-breaking History of American Sculpture published that year, Lorado Taft devoted several pages to Borglum,[27] and he was the subject of an entire chapter in Charles Caffin’s 1903 book American Masters of Sculpture.[28] In 1904 Borglum won the gold medal at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis. Borglum received several major public commissions, including an equestrian monument of General John Brown Gordon for the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta (1907), one of Rough Rider Buckey O'Neill for the plaza in front of the courthouse in Prescott, Arizona (1907), and The Pioneer, which was erected in the Court of Honor at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco (1915). Two of his works are located in Jersey City, New Jersey. His sculpture Buffalo and Bears is in Leonard Gordon Park in the city's Heights section[29] In 1974 a group of the sculptor's descendants gave twenty bronzes, marbles, original plasters, portfolios of drawings and paintings to the New Britain Museum of American Art. Today the Museum houses the largest repository of Borglum's works. Borglum sculpted a larger than life bronze equestrian statue for the Bucky O'Neill Monument, Rough Rider at the Yavapai County Court House Plaza in Prescott, Arizona.[30] Teddy Roosevelt had persuaded Buckey O'Neill to join the Rough Riders and he was killed at the Battle of San Juan Hill. Borglum's statue Cowboy at Rest is also located on the grounds of the Yavapai County Court House in Prescott, Arizona.[31] Borglum's pieces can be found at the Buffalo Bill Museum in Cody, Wyoming, including Evening, a depiction of a cowboy leaning against his unsaddled horse at the end of the day. Two of Borglum's sculptures, Inspiration and Aspiration, which depict Native American men, stand in the front courtyard of St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery, in the East Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City, flanking the front gate. Black and white photos of Cowboy Mounting, Lost in a Blizzard (in marble), and Tamed can be found in Caffin's book.[32] List of works[33]

Gallery of works by Solon Borglum Bucky O'Neill Monument, Rough Rider Prescott, Arizona John Brown Gordon statue, on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol Bust of Giles A. Smith at Vicksburg National Military Park Bust of Edward D. Tracy at Vicksburg National Military Park ReferencesNotes

Bibliography

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Solon Borglum.

|

||||||||||||