|

Solomon Islands rain forests

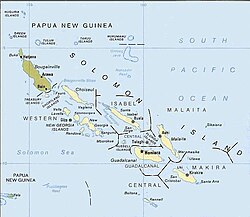

The Solomon Islands rain forests are a terrestrial ecoregion covering the Solomon Islands archipelago.[2][3][4] GeographyThe ecoregion covers the Solomon Islands archipelago, which is divided between the countries of Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. The archipelago's northern islands, Bougainville and Buka, are part of Papua New Guinea. The rest of the archipelago is within the nation of Solomon Islands. The ecoregion excludes the eastern islands of the nation of Solomon Islands, the Santa Cruz Islands, which lie in the Vanuatu rain forests ecoregion together with the neighbouring archipelago of Vanuatu.[5] The archipelago extends approximately 1450 km from northwest to southeast, between 5° and 12° South latitude.[6] Bougainville is the largest island, about 200 km long and from 50 to 60 km wide with an area of almost 9000 km2. The island has a central mountain range, the northern part of which is known as the Emperor Range, and the southern part, separated by a lower saddle, as the Crown Prince Range. Mount Balbi in the Emperor Range, at 2,715 metres elevation, is the highest peak in the archipelago. Volcanic rocks are common, with dating back approximately 30 million years. The Panguna mine in the Crown Prince Range, currently closed, is one of the largest copper mines on earth. The Keriaka Plateau in northwest Bougainville, south of Mount Balbi, is a karst plateau formed of weathered foraminiferous limestone dating to the lower Miocene.[6] Buka Island lies northwest of Bougainville, separated by a narrow strait. Much of the island is made up of uplifted Pleistocene coralline limestone.[6] The rest of the archipelago extends southeast of Bougainville as a double chain. The outer or northeastern chain comprises the islands of Choiseul, Santa Isabel, and Malaita, which are each about 200 km long and 30 km wide. The islands have mountainous interiors extending above 1000 m on Choiseul, 1200 m on Santa Isabel, and 1300 m on Malaita.[6] The inner chain extends from Shortland Island, 20 km southeast of Bougainville, and includes Vella Lavella, Ganongga, Kolombangara, the New Georgia Islands (New Georgia, Rendova, Vangunu, and Nggatokae), the low coralline Russell Islands, Guadalcanal, and San Cristobal. Guadalcanal has the highest mountains of the inner and outer chains, and Mount Popomanaseu on Guadalcanal is the highest peak outside Bougainville at 2331 metres elevation. Honiara, the capital of the Solomon Islands, is on the north shore of Guadalcanal. The inner chain islands are mostly below 1000 meters elevation, with the exception of the conical stratovolcano Kolombangara which reaches 1,770 metres.[6] Most of the inner and outer chain islands are made up of volcanic rocks, including andesite and basalt. Guadalcanal has the most complex geology, with areas of andesite volcanics, intrusive plutonic rocks, Pliocene sedimentary rocks, and uplifted Pleistocene coralline limestone in the northern lowlands near Honiara. There are outcrops of ultramafic rock, rich in chromium and nickel, on five islands – at Santa Isabel's southern tip, on the nearby island of San Jorge, in the Florida Islands, in southwestern Guadalcanal, and in north-central San Cristobal. These rocks are toxic to many plants, and are often home to distinctive plant communities.[6] The archipelago includes two groups of low coralline outlying islands – Ontong Java, northeast of the outer chain and 450 km north of Honiara, and Rennell and Bellona, south of San Cristobal and 250 km south of Honiara.[6] The ecoregion is part of the Australasian realm, which also includes the neighbouring Bismarck Archipelago and New Guinea, as well as New Caledonia, Australia and New Zealand.[5] Floristically it is the easternmost part of the Papuasia region, which includes New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago.[5] ClimateThe islands have a humid tropical climate. Rainfall averages between 3000 and 5000 mm annually at most sea-level stations. There is little seasonal variation in temperature, with seasonal variation in rainfall depending on the prevailing winds. The southeast trade winds are active from about March to October when the sun is north of the equator. February-March and November-December are unsettled weather periods when the islands can get drenched with convectional rains. Winds come from the northwest from December to February. The southern islands can experience tropical cyclones, which usually develop between November and April. Guadalcanal's relatively high east-west running mountains create a rain shadow effect in the island's northeastern lowlands, with lower rainfall during the southwest trade wind season than elsewhere in the archipelago.[6] Temperatures above 700 meters elevation are generally 4 to 5 °C cooler than the lowlands, with mean annual temperatures of 22 to 23 °C. The highlands experience cloud cover during the southeast trade wind season, and windward slopes have higher rainfall than the lowlands.[6] Flora The natural vegetation of the Solomon archipelago consists mostly of lowland and montane tropical rain forests. The major plant communities include coastal strand, mangrove forests, freshwater swamp forests, lowland rain forests, and montane rain forests. Seasonally-dry forests and grasslands are found on the northern (leeward) slopes of Guadalcanal.[7] Lowland forests are made up of trees up to 35 meters high forming a closed canopy, with Vitex cofassus and Pometia pinnata as common canopy trees along with species of Ficus, Alstonia, Celtis, Elaeocarpus, Canarium, Syzygium, Calophyllum, Didymocheton, Dysoxylum, Terminalia, and Sterculia. Understorey plants include the palms Licuala, Caryota, and Areca, bamboos, tree ferns (Cyathea sp.), Pandanus, and giant herbs. Bananas, gingers, lianas, and rattans grow forest gaps where sunlight reaches through the canopy. Epiphytes, particularly ferns and orchids, grow abundantly on the forest trees.[6] Montane forests in the Solomons share many species with the lowland forests, and differ primarily having a lower canopy height – 20 to 25 meters. The Solomons' montane forests are absent many of the tree species characteristic of montane forests in the Bismarcks and New Guinea, including Nothofagus (southern beech) and Fagaceae (species of Castanopsis and Lithocarpus).[6] On Bougainville, lowland forest transitions to submontane forest above 750 to 800 metres elevation extending up to 1500 metres or higher. Submontane forests have a lower canopy, 25 to 30 metres high, dominated by species of Garcinia and Elaeocarpus, together with species of Dillenia, Schizomeria, Syzygium, Casuarina, Alphitonia, Cryptocarya, and Bischofia javanica. Characteristic submontane plants include Neonauclea, Sloanea, Cryptocarya, Palaquium, Canarium, and Ficus.[6] Above 1500 metres elevation on Bougainville the forests transition to montane scrub of Pandanus and the palm Hydriastele macrospadix, or tree fern (Cyathea sp.) and bamboo scrub on more recent volcanic deposits, with pockets of submontane forest in sheltered areas with deeper soils.[6] In northern Guadalcanal, where the rain shadow of the mountains creates drier conditions from June to October, there are areas of mixed-deciduous forest and grassland. The mixed-deciduous forest has an open, fragmented canopy with Pometia pinnata, Vitex cofassus, and Kleinhovia hospita common. Deciduous trees include Pterocarpus indicus, Antiaris toxicaria, and species of Ficus and Sterculia. Small and understorey trees include the poisonous Semecarpus spp., Colona scabra, and Cananga odorata. Mixed-deciduous forest extends into grasssland areas as gallery forest along streams and rivers.[6] Tall grasslands extend about 30 km east from Honiara. They are dominated by Themeda triandra growing 1 meter or taller, along with Phragmites karka and various introduced grasses including Imperata cylindrica and Setaria parviflora.[6] Hydriastele hombronii is a palm endemic to outcrops of ultrabasic soil on Choiseul, Santa Isabel, and several other islands.[6] FaunaThe islands are home to 47 native mammal species, limited to bats and murid rodents. 26 species are endemic or near-endemic – 17 species of bats, and nine species of murid rodent. Endemic murid rodents are the Bougainville mosaic-tailed rat (Melomys bougainville), Buka Island mosaic-tailed rat (Melomys spechti), Poncelet's giant rat Solomys ponceleti), Ugi naked-tailed rat (Solomys salamonis), Bougainville naked-tailed rat (Solomys salebrosus), Isabel naked-tailed rat (Solomys sapientis), Emperor rat (Uromys imperator), Guadalcanal rat (Uromys porculus), and king rat (Uromys rex).[5] 199 bird species are native to the Solomon archipelago, of which 69 species are endemic.[7] The ecoregion corresponds to the Solomon group endemic bird area.[8] PeopleThe first evidence of human inhabitation of the archipelago is at Kilu Cave on Buka, dating back 29,000 years ago to the Pleistocene. The settlers likely crossed the sea from the Bismarck Archipelago. At the time sea levels were lower, and New Ireland was separated from the Solomons by 180 km. The lower sea levels also joined several of the islands, including Buka, Bougainville, Choiseul, Santa Isabel, and the Florida Islands, into a single island known as Greater Bougainville or Greater Bukida.[9] Early settlers were likely highly mobile hunter-gatherers. Evidence from Kilu Cave show that early residents hunted bats, reptiles, rats, and birds from at least six families including several species of pigeon, a megapode, and a rail, along with marine shells and fish bones indicating inshore fishing. Residents also ate starches from taro (Colocasia esculenta) and Alocasia sp. The nut-producing trees Canarium indicum and Canarium salomonense were introduced to the Solomons from the New Guinea mainland about 10,000 years ago. Sea levels rose to close to current levels between 5500 and 6000 years before present (B.P.). Lapita settlers, the ancestors of today's Oceanic Austronesian peoples, arrived by 3400 B.P., and introduced the marsupial gray cuscus (Phalanger orientalis) to the islands.[9] The people of the Solomons today are diverse in culture and language. Between 70 and 80 languages are spoken in the archipelago. There is a cultural distinction between “salt-water” and “bush” people, with bush people dwelling inland with lifestyles and traditions centred on the forest and gardens, and “salt water” people dwelling near the coast with a lifestyle and culture oriented to the sea. In parts of the archipelago, like the Western Solomons, the island interiors are now little inhabited.[9] Many islanders engage in subsistence gardening. Bush fallowing is common practice, rotating gardens in a confined area of forest over relatively short period, then leaving sections fallow so that shrub-forest and soil fertility can recover. Primary forest trees which produce edible nuts and fruits, including Canarium species, Barringtonia species, Artocarpus altilis, and Pangium edule, are usually retained when shrub-forest is cleared for gardens.[6] Conservation and threatsMost of the mountain forests are relatively intact, while areas of the lowlands have been cleared for farms and gardens and plantations of coconut (Cocos nucifera) and other food, fiber, timber-producing trees. Much of the grassland east of Honiara has been replaced by plantations of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis).[6] Commercial logging began in the 1920s, and has removed large areas of forest across the archipelago, mostly in the lowlands. Kolombangara is one of the most intensively logged islands in the archipelago. Clear-cut logging began in the 1960s, and by 2012 less than 10% of the island's primary forest remained, restricted to inaccessible ridgetops, ravines, and within the central crater.[10] 1.2% of the ecoregion is in protected areas.[3] They include Queen Elizabeth National Park on Guadalcanal (10.9 km2), East Rennell World Heritage Site (370 km2) on Rennell Island, Kolombangara Forest Reserve (200 km2) on Kolombangara, and Padezaka Tribal Forest Conservation Area (48.23 km2), Sirebe Forest Conservation Area (8.0 km2), Siporae Tribal Forest Conservation Area (6.66 km2), and Vuri Forest Conservation Area (5.74 km2) on Choiseul.[3][11] External links

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||