|

Romania–Turkey relations

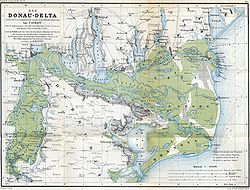

Romanian–Turkish relations are foreign relations between Romania and Turkey. The two countries maintain longstanding historical, geographic, and cultural relations. Romania has an embassy in Ankara and two consulates-general in Istanbul and İzmir. Romania also has four honorary consulates in Turkey in İskenderun, Edirne, Trabzon and Eskişehir. Romania also has a cultural institute The Romanian Cultural Institute "Dimitrie Cantemir". Turkey has an embassy in Bucharest and a consulate-general in Constanţa. Turkey also has two honorary consulates in Cluj-Napoca and Iași. Both countries are full members of NATO, the BLACKSEAFOR and BSEC. HistoryTurkic settlement has a long history in the Dobruja region, various groups such as Bulgars, Pechenegs, Cumans and Turkmen settling in the region between the 7th and 13th centuries, and probably contributing to the formation of a Christian autonomous polity in the 14th century.[1] The existence of a strictly Turkish population in the territories of modern Romania can possibly be tracked down to the 13th century. In 1243, the Seljuk Turks in Anatolia (most of modern Turkey) were defeated by the Mongols in the Battle of Kösedağ. The Mongols subordinated the Seljuk Turks and divided their lands between two brothers, Kilij Arslan IV and Kaykaus II. Kaykaus II, having been forced to obey his brother, opposed this, for which he had to leave Anatolia together with a large group of partisans and look for refuge in the Byzantine Empire.[2] He and his partisans were settled by Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos in a region between Varna and the Danube Delta which is known as Dobruja today. Later, Kaykaus II would attempt an unsuccessful rebellion in the Byzantine Empire and went into exile in Crimea, but his partisans remained in Dobruja and he would be succeeded as leader by Sarı Saltık.[3] In 1307, some of the Dobrujan Seljuk Turks would return to Anatolia.[2] Nevertheless, some would stay in the area, and while they kept their language, they would convert to Christianity.[3] It has been suggested that these Seljuk Turks eventually evolved into the modern Gagauz people, the name of which would supposedly come from Kaykaus II.[4] Another important event in the history of the Turkish population in Romania was the Ottoman conquest of the region in the early 15th century. Hence, by the 17th century most of the settlements in Dobruja had Turkish names, either due to colonisations[1] or through assimilation of the Islamised pre-Ottoman Turkic populations. In the nineteenth century, Turks and Tatars were more numerous in Dobruja than the Romanians.[5]    Northern Dobruja region was annexed by the Ottoman Empire in 1420, the region remained under Ottoman control until the late 19th century. Initially, it was organised as an udj (border province), included in the sanjak of Silistra, part of the Eyalet of Rumelia. Later, under Murad II or Suleiman I, the sanjak of Silistra and surrounding territories were organised as a separate eyalet.[6] In 1555, a revolt led by the "false" (düzme) Mustafa, a pretender to the Turkish throne, broke out against Ottoman administration in Rumelia and rapidly spread to Dobruja, but was repressed by the beylerbey of Nigbolu.[7][8] In 1603 and 1612, the region suffered from the forays of Cossacks, who burnt down Isaķči and plundered Küstendje. In the two Danubian Principalities, Ottoman suzerainty had an overall reduced impact on the local population, and the impact of Islam was itself much reduced. Wallachia and Moldavia enjoyed a large degree of autonomy, and their history was punctuated by episodes of revolt and momentary independence. After 1417, when Ottoman domination over Wallachia first became effective, the towns of Turnu and Giurgiu were annexed as kazas, a rule enforced until the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829 (the status was briefly extended to Brăila in 1542).[9] For the following centuries, three conversions in the ranks of acting or former local hospodars are documented: Wallachian Princes Radu cel Frumos (1462–1475) and Mihnea Turcitul (1577–1591), and Moldavian Prince Ilie II Rareș (1546–1551). At the other end of the social spectrum, Moldavia held a sizable population of Tatar slaves, who shared this status with all local Roma people (see Slavery in Romania). While Roma slavery also existed in Wallachia, the presence of Tatar slaves there has not been documented, and is only theorized.[10] The population may have foremost comprised Muslim Nogais from the Budjak who were captured in skirmishes, although, according to one theory, the first of them may have been Cumans captured long before the first Ottoman and Tatar incursions.[10] The issue of Ottoman presence on the territory of the two countries is often viewed in relation to the relations between the Ottoman Sultans and local Princes. Romanian historiography has generally claimed that the latter two were bound by bilateral treaties with the Porte. One of the main issues was that of Capitulations (Ottoman Turkish: ahdnâme), which were supposedly agreed between the two states and the Ottoman Empire at some point in the Middle Ages. Such documents have not been preserved: modern Romanian historians have revealed that Capitulations, as invoked in the 18th and 19th centuries to invoke Romanian rights vis à vis the Ottomans, and as reclaimed by nationalist discourse in the 20th century, were forgeries.[11] Traditionally, Ottoman documents referring to Wallachia and Moldavia were unilateral decrees issued by the Sultan.[11] In one compromise version published in 1993, Romanian historian Mihai Maxim argues that, although these were unilateral acts, they were viewed as treaties by the Wallachian and Moldavian rulers.[12]    Alongside Dobruja, a part of present-day Western Romania came under direct Ottoman rule in 1551-1718, was the Eyalet of Temeşvar (today's Timișoara), compromising the regions of Banat and southern Crișana. The Ottoman rule extended to Arad (1551–1699) and as far as Oradea (1661–1699) in northern Crișana.[9] Numerous Ottoman Muslims settled in the area, living mostly in the cities and associated with trade and administration. The Banat region was mainly populated by Rascians (Serbs) in the west,[13] and Vlachs (Romanians) in the east. Thus, in some historical sources, the region of Banat was referred to as Rascia, while in others as Wallachia.[13] The thousand Ottoman Muslims settled there were, where however, driven out by Habsburg conquest and settled at Ada Kaleh on the Danube river. By the 17th century, according to the notes of traveler Evliya Çelebi, Dobruja was also home to a distinct community of people of mixed Turkish and Wallachian heritage.[9] Additionally, a part of the Dobrujan Roma community has traditionally adhered to Islam;[9][14] it is believed that it originated with groups of Romani people serving in the Ottoman Army during the 16th century,[14] and has probably incorporated various ethnic Turks who had not settled down in the cities or villages.[15] The presence of Ottoman Muslims in the two Danubian Principalities was also attested, centering on Turkish traders[16][17] and small communities of Muslim Roma.[17] It is also attested that, during later Phanariote rules and the frequent Russo-Turkish Wars, Ottoman troops were stationed on Wallachia's territory.[18] The thousand Ottoman Muslims settled in present day Banat and Crișana were driven out by Habsburg monarchy after defeating the Ottoman rule, and most of them settled in Ada Kaleh on the Danube river. As a result an important Turkish community used to live until 1967 on the island of Ada Kaleh in Banat on the Danube river. The Island was inhabited by Turkish people from all parts of the Ottoman Empire who mostly produced Turkish goods for the surrounding region. Adakale Turkish belongs to the Rumelian subgroup (also known as Balkan subgroup) of the Turkish language.[19] Before 1970, Adakale used to be the northernmost part where Western Rumelian was spoken. [20]   The Dobrujan Muslim community was exposed to cultural repression during Communist Romania. After 1948, all property of the Islamic institutions became state-owned.[21] The following year, the state-run and secular compulsory education system set aside special classes for Tatar and Turkish children.[21] According to Irwin, this was part of an attempt to create a separate Tatar literary language, intended as a means to assimilate the Tatar community.[22] A reported decline in standards led to the separate education agenda being ceased in 1957.[21] As a consequence, education in Tatar dialects and Turkish was eliminated in stages after 1959, becoming optional,[15] while the madrasah in Medgidia was shut down in the 1960s.[15][23] The population of Ada Kaleh relocated to Anatolia shortly before the 1968 construction of the Iron Gates dam by a joint Yugoslav-Romanian venture, which resulted in the island being flooded. At the same time, Sufi tradition was frowned upon by Communist officials—as a result of their policies, the Sufi groups became almost completely inactive.[24] Traditionally, large scale Turkish Romanian migration has been to the Republic of Turkey where most arrived as muhacirs ("refugees") during the First World War and the Second World War. Furthermore, during the early 20th century, some Turkish Romanians also migrated to North America and later to Western Europe, especially Austria, Germany, France and Netherlands. EconomyThe countries are each other's largest trading partners in Southeastern Europe.

Turkey is among the largest investors in Romania with its current value of investment exceeding 7,5 billion USD including those coming from third countries. Approximately 7.000 Turkish companies actively operate in Romania. Romania continues to offer significant opportunities for both Turkish exports and investments.[25] Turkey has been and remains one of the most popular tourist destinations for Romanians, especially Istanbul and Aegean and Mediterranean Sea coasts. 886,555 Romanian tourists visited Turkey in 2022.[26] 728,255 Turkish citizens in turn visited Romania in 2022.[27] Major airline Turkish Airlines and other Turkish air companies operate between Turkey and several cities in Romania on a daily basis. Strategic partnershipBased on the mutual commitment to enhance bilateral relations in every field, the level of the relations between the two countries were raised to strategic partnership with the signing of Strategic Partnership Declaration in December 2011. The Action Plan on the implementation of the Declaration was signed in March 2013. The 10th anniversary of the Strategic Partnership in 2021 was celebrated with various events held in both Ankara and Bucharest.[28] Accession of Turkey to the European UnionRomania strongly supports Turkish Membership in the European Union. Even before its official accession to the EU on 1 January 2007, Romania openly and strongly supported Turkey's membership and the opening of new chapters of negotiations. This support came as a natural consequence of an excellent track record of collaboration between the two countries on multiple levels (including mutual interests and challenges in the Black Sea region). It is also important to underline that Turkey was also one of the main supporter of Romania in its accession to NATO.[29] After Romania joined the EU, the supportive position towards Turkish membership within the government as well as the opposition was even strengthened. Traian Băsescu, former President of Romania (until 2014) and Klaus Iohannis, the current President, expressed their strong support towards Turkey's EU membership, qualifying the strategic partnership between the two countries as excellent.[29] Romanian public opinion regarding Turkey's EU accession, has mostly been supportive. According to the Eurobarometer from 2008, Romania even recorded the highest percentage (among the EU member states) of citizens who supported Turkey's membership – 64 percent.[29] High level visits

Resident diplomatic missions

See also

References

Sources

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||