|

Riga Metro

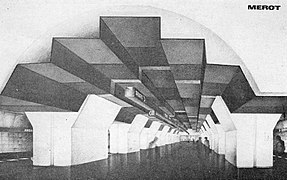

The Riga Metro (Latvian: Rīgas metro) was a planned metro system in Riga, Latvia,[1] during the time of the Soviet Union. Three lines with a total of 33 stations were planned to be built by 2021, however in the late 1980s, during the Singing Revolution, the whole project met with opposition and combined with the fall of the Soviet Union, construction, which was planned to begin in 1990, never took place. The population of the city has been declining due to emigration and negative population growth rate since 1990, making the prospects of a full metro system, even with EU funding, unrealistic in the near future. In fact, after the fall of the Soviet Union, possible construction of the metro system has seldom been publicly discussed, even dismissed as unnecessary. History The idea of the Riga Metro emerged in the mid 1970s, when city planners were examining how to integrate traffic systems into the capital. Several concepts were proposed, including the reconstruction of the city's railway or the installation of high-speed tram lines. However, officials regarded both proposals as inefficient. The most pressing issue was that Riga's population was rising quickly and was expected to eventually surpass one million, the requirement for constructing a metro in the Soviet Union. The Metrogiprotrans institute in Moscow was to design the layout of the metro system, work out the economic planning, and develop the detailed design of the project itself. The technical and economic basis of the project was to be completed by 1978. Another three years were scheduled for further elaboration of the project, with another nine years for the construction of the first eight metro stations. According to this plan, the first underground line was supposed to be opened in 1990. However, the development process faced continued delays, resulting in the technical and economic planning of the project being finished two years late, in 1980. A further five-year delay followed, stalling construction work of the metro line and stations, which could not begin before the all preparation work was finished. Due to hard geological condition of soils the design of the first section in 1984 was redirected to the Lenmetroproekt institute in Leningrad, who were more experienced in these conditions (Leningrad having similar geology). This resulted in the opening date of Riga metro being rescheduled to 1997 at the earliest. Art-decor design of interior of stations was given to local architects that had an experience already after a development of Rizhskaya station of Moscow Metro. In 1986 the plan-general of metro system was updated to include three lines instead of two. Despite continued delays, the project phase of the first section was completed in 1989, its preparation for build phase started at 1986 while a construction phase would to be in 1990, and the opening date planned for 2000–2002. At the end of the 1980s, the project began to receive strong criticism, and, as a result of public dissatisfaction combined with the fall of the Soviet Union, the planned construction during the 1990s never began. Lines The original plan called for two lines, but then a third line had been included. First plan

Second plan

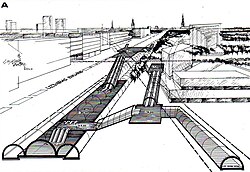

First sectionThe first planned section was 8.3 km long, took 12 minutes to travel from one terminus to the other and had 8 stations (4 of which were deep below ground in the centre): "Zasulauks", "Agenskalns" (formerly "Aurora"), "Daugava" (formerly "Uzvaras"), "Station" (former "Central"), "Druzhba"(Friendship) (formerly "Kirov"), "Vidzeme market" (formerly "Rainis", "Revolution"), "Oshkalny", "VEF"

Monetary issuesThe first metro in the Soviet Baltic republics was also to have been the most expensive one in the Soviet Union. It was estimated that the cost of one kilometre would be 25–26 million Soviet rubles[speculation?]. At the time the Riga metro was being planned, the metro in Minsk, Belarus was being built at a cost of 15 million Soviet rubles per kilometre. Officials in Riga were not very concerned with funding, as the necessary money would come mainly from Moscow. The budget of the Latvian SSR would have been responsible for funding the train depot (10–12 million Soviet rubles), engineering details (2.5 million Soviet rubles), and station vestibules (4–5 million Soviet rubles). As a result, Riga would have been expected to spend less than 20 million Soviet rubles for the city's metro. However, the city would have had competition for funding from Moscow, as Odessa and Omsk were also eager for financial assistance in establishing their own metro systems at the same time. CriticismObjections against the Riga metro began to be raised as the final design proposal was being finalised. The most pressing concerns, raised by the local scientific community, regarded the usefulness and effectiveness of such a massive and challenging project. They argued that the project would bring more harm than benefits to the city, as the ground waters in Riga are very high with migrating currents, and, as a result, nobody could tell where they would be after a decade. If ground waters were to flow across metro lines, the metro system would get flooded. However, this same argument did not prevent the construction of a metro in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), which has similar geological features to Riga. As perestroika began to become established in the Soviet Union, the local press became filled with geologic and geodesic articles and how these issues could affect a potential metro in the city. In addition to concerns about potential flooding, the project's authors were also blamed for having planned stations at inconvenient locations, and that the idea itself of a metro was becoming outmoded. After these arguments were evaluated and dismissed, the autochthonous population of Latvia began protesting against another likely wave of migration of Slavs into Riga as the construction would attract another tens of thousands of workers from other Soviet republics to the city where the share of Latvians had fallen from more than 60% in the 1930s to less than 36% in the 1980s. It was said that such a new wave of migration would pose an even larger threat to the identity of Latvia, where the share of Latvians fell in the late 1980s to just 52%, and to the Latvian language. CancellationThe end of the 1980s brought about disputes and doubts regarding the decisions of the Riga and Latvian governments concerning the metro, as well as the competence of specialists from Moscow. In 1987, ecological activists organised an act of protest; despite the protest, however, the decision was made to start work on the second stage of technological and economic planning. However, local specialists were asked to take over much of the work to reduce Latvia's reliance on specialists from Moscow. After two months, the planning commission came to the conclusion that there was no economic or technological basis to continue the project, and twelve years of planning ended without any work actually done. See alsoReferences |

||||||||||||||||