|

Privateer

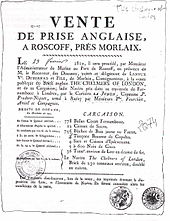

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war.[1] Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or delegated authority issued commissions, also referred to as letters of marque, during wartime. The commission empowered the holder to carry on all forms of hostility permissible at sea by the usages of war. This included attacking foreign vessels and taking them as prizes and taking crews prisoner for exchange. Captured ships were subject to condemnation and sale under prize law, with the proceeds divided by percentage between the privateer's sponsors, shipowners, captains and crew. A percentage share usually went to the issuer of the commission (i.e. the sovereign). Privateering allowed sovereigns to raise revenue for war by mobilizing privately owned armed ships and sailors to supplement state power. For participants, privateering provided the potential for a greater income and profit than obtainable as a merchant seafarer or fisher. However, this incentive increased the risk of privateers turning to piracy when war ended. The commission usually protected privateers from accusations of piracy, but in practice the historical legality and status of privateers could be vague. Depending on the specific sovereign and the time period, commissions might be issued hastily; privateers might take actions beyond what was authorized in the commission, including after its expiry. A privateer who continued raiding after the expiration of a commission or the signing of a peace treaty could face accusations of piracy. The risk of piracy and the emergence of the modern state system of centralised military control caused the decline of privateering by the end of the 19th century. Legal framework and relation to piracyThe commission was the proof the privateer was not a pirate. It usually limited activity to one particular ship, and specified officers, for a specified period of time. Typically, the owners or captain would be required to post a performance bond. The commission also dictated the expected nationality of potential prize ships under the terms of the war. At sea, the privateer captain was obliged to produce the commission to a potential prize ship's captain as evidence of the legitimacy of their prize claim. If the nationality of a prize was not the enemy of the commissioning sovereign, the privateer could not claim the ship as a prize. Doing so would be an act of piracy. In British law, under the Offences at Sea Act 1536, piracy, or raiding a ship without a valid commission, was an act of treason. By the late 17th century, the prosecution of privateers loyal to the usurped King James II for piracy began to shift the legal framework of piracy away from treason towards crime against property.[2] As a result, privateering commissions became a matter of national discretion. By the passing of the Piracy Act 1717, a privateer's allegiance to Britain overrode any allegiance to a sovereign providing the commission. This helped bring privateers under the legal jurisdiction of their home country in the event the privateer turned pirate. Other European countries followed suit. The shift from treason to property also justified the criminalisation of traditional sea-raiding activities of people Europeans wished to colonise. The legal framework around authorised sea-raiding was considerably murkier outside of Europe. Unfamiliarity with local forms of authority created difficulty determining who was legitimately sovereign on land and at sea, whether to accept their authority, or whether the opposing parties were, in fact, pirates. Mediterranean corsairs operated with a style of patriotic-religious authority that Europeans, and later Americans, found difficult to understand and accept.[citation needed] It did not help that many European privateers happily accepted commissions from the deys of Algiers, Tangiers and Tunis. [citation needed] The sultans of the Sulu archipelago (now present-day Philippines) held only a tenuous authority over the local Iranun communities of slave-raiders. The sultans created a carefully spun web of marital and political alliances in an attempt to control unauthorised raiding that would provoke war against them.[3] In Malay political systems, the legitimacy and strength of their Sultan's management of trade determined the extent he exerted control over the sea-raiding of his coastal people.[4] Privateers were implicated in piracy for a number of complex reasons. For colonial authorities, successful privateers were skilled seafarers who brought in much-needed revenue, especially in newly settled colonial outposts.[5] These skills and benefits often caused local authorities to overlook a privateer's shift into piracy when a war ended. The French Governor of Petit-Goave gave buccaneer Francois Grogniet blank privateering commissions, which Grogniet traded to Edward Davis for a spare ship so the two could continue raiding Spanish cities under a guise of legitimacy.[6] New York Governors Jacob Leisler and Benjamin Fletcher were removed from office in part for their dealings with pirates such as Thomas Tew, to whom Fletcher had granted commissions to sail against the French, but who ignored his commission to raid Mughal shipping in the Red Sea instead.[7] Some privateers faced prosecution for piracy. William Kidd accepted a commission from King William III of England to hunt pirates but was later hanged for piracy. He had been unable to produce the papers of the prizes he had captured to prove his innocence.[8] Privateering commissions were easy to obtain during wartime but when the war ended and sovereigns recalled the privateers, many refused to give up the lucrative business and turned to piracy.[9] Boston minister Cotton Mather lamented after the execution of pirate John Quelch:[10]

Noted privateersPrivateers who were considered legitimate by their governments include:

ShipsEntrepreneurs converted many different types of vessels into privateers, including obsolete warships and refitted merchant ships. The investors would arm the vessels and recruit large crews, much larger than a merchantman or a naval vessel would carry, in order to crew the prizes they captured. Privateers generally cruised independently, but it was not unknown for them to form squadrons, or to co-operate with the regular navy. A number of privateers were part of the English fleet that opposed the Spanish Armada in 1588. Privateers generally avoided encounters with warships, as such encounters would be at best unprofitable. Still, such encounters did occur. For instance, in 1815 Chasseur encountered HMS St Lawrence, herself a former American privateer, mistaking her for a merchantman until too late; in this instance, however, the privateer prevailed. The United States used mixed squadrons of frigates and privateers in the American Revolutionary War. Following the French Revolution, French privateers became a menace to British and American shipping in the western Atlantic and the Caribbean, resulting in the Quasi-War, a brief conflict between France and the United States, fought largely at sea, and to the Royal Navy's procuring Bermuda sloops to combat the French privateers.[11] Overall history In Europe, the practice of authorising sea-raiding dated to at least the 13th century but the word 'privateer' was coined sometime in the mid-17th century.[12] Seamen who served on naval vessels were paid wages and given victuals, whereas mariners on merchantmen and privateers received a share of the takings.[13] Privateering thus offered otherwise working-class enterprises (merchant ships) with the chance at substantial wealth (prize money from captures). The opportunity mobilized local seamen as auxiliaries in an era when state capacity limited the ability of a nation to fund a professional navy via taxation.[14] Privateers were a large part of the total military force at sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. In the first Anglo-Dutch War, English privateers attacked the trade on which the United Provinces entirely depended, capturing over 1,000 Dutch merchant ships. During the subsequent war with Spain, Spanish and Flemish privateers in the service of the Spanish Crown, including the Dunkirkers, captured 1,500 English merchant ships, helping to restore Dutch international trade.[citation needed] British trade, whether coastal, Atlantic, or Mediterranean, was also attacked by Dutch privateers and others in the Second and Third Anglo-Dutch wars. Piet Pieterszoon Hein was a brilliantly successful Dutch privateer who captured a Spanish treasure fleet. Magnus Heinason was another privateer who served the Dutch against the Spanish. While their and others' attacks brought home a great deal of money, they hardly dented the flow of gold and silver from Mexico to Spain. As the Industrial Revolution proceeded, privateering became increasingly incompatible with modern states' monopoly on violence. Modern warships could easily outrace merchantmen, and tight controls on naval armaments led to fewer private-purchase naval weapons.[14] Privateering continued until the 1856 Declaration of Paris, in which all major European powers stated that "Privateering is and remains abolished". The United States did not sign the Declaration over stronger language that protects all private property from capture at sea, but has not issued letters of marque in any subsequent conflicts. In the 19th century, many nations passed laws forbidding their nationals from accepting commissions as privateers for other nations. The last major power to flirt with privateering was Prussia in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, when Prussia announced the creation of a 'volunteer navy' of ships privately-owned and -manned, but eligible for prize money. (Prussia argued that the Declaration did not forbid such a force, because the ships were subject to naval discipline.) England/BritainIn England, and later the United Kingdom, the ubiquity of wars and the island nation's reliance on maritime trade enabled the use of privateers to great effect. England also suffered much from other nations' privateering. During the 15th century, the country "lacked an institutional structure and coordinated finance".[13] When piracy became an increasing problem, merchant communities such as Bristol began to resort to self-help, arming and equipping ships at their own expense to protect commerce.[15] The licensing of these privately owned merchant ships by the Crown enabled them to legitimately capture vessels that were deemed pirates. This constituted a "revolution in naval strategy" and helped fill the need for protection that the Crown was unable to provide. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth (1558–1603), she "encouraged the development of this supplementary navy".[16] Over the course of her rule, the increase of Spanish prosperity through their explorations in the New World and the discovery of gold contributed to the deterioration of Anglo-Spanish relations.[17] Elizabeth's authorisation of sea-raiders (known as Sea Dogs) such as Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh allowed her to officially distance herself from their raiding activities while enjoying the gold gained from these raids. English ships cruised in the Caribbean and off the coast of Spain, trying to intercept treasure fleets from the Spanish Main.[18] During the Anglo-Spanish War (1585-1604) England continued to rely on private ships-of-war to attack Iberian shipping because the Queen had insufficient finance to fund this herself.[19] After the war ended many unemployed English privateers turned to piracy.[20] Elizabeth was succeeded by the first Stuart monarchs, James I and Charles I, who did not permit privateering. Desperate to fund the expensive War of Spanish Succession, Queen Anne restarted privateering and even removed the need for a sovereign's percentage as an incentive.[2] Sovereigns continued to license British privateers throughout the century, although there were a number of unilateral and bilateral declarations limiting privateering between 1785 and 1823. This helped establish the privateer's persona as heroic patriots. British privateers last appeared en masse in the Napoleonic Wars.[21]  England and Scotland practiced privateering both separately and together after they united to create the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. It was a way to gain for themselves some of the wealth the Spanish and Portuguese were taking from the New World before beginning their own trans-Atlantic settlement, and a way to assert naval power before a strong Royal Navy emerged. Sir Andrew Barton, Lord High Admiral of Scotland, followed the example of his father, who had been issued with letters of marque by James III of Scotland to prey upon English and Portuguese shipping in 1485; the letters in due course were reissued to the son. Barton was killed following an encounter with the English in 1511. Sir Francis Drake, who had close contact with the sovereign, was responsible for some damage to Spanish shipping, as well as attacks on Spanish settlements in the Americas in the 16th century. He participated in the successful English defence against the Spanish Armada in 1588, though he was also partly responsible for the failure of the English Armada against Spain in 1589. Sir George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, was a successful privateer against Spanish shipping in the Caribbean. He is also famous for his short-lived 1598 capture of Fort San Felipe del Morro, the citadel protecting San Juan, Puerto Rico. He arrived in Puerto Rico on June 15, 1598, but by November of that year, Clifford and his men had fled the island due to fierce civilian resistance. He gained sufficient prestige from his naval exploits to be named the official Champion of Queen Elizabeth I. Clifford became extremely wealthy through his buccaneering but lost most of his money gambling on horse races.  Captain Christopher Newport led more attacks on Spanish shipping and settlements than any other English privateer. As a young man, Newport sailed with Sir Francis Drake in the attack on the Spanish fleet at Cadiz and participated in England's defeat of the Spanish Armada. During the war with Spain, Newport seized fortunes of Spanish and Portuguese treasure in fierce sea battles in the West Indies as a privateer for Queen Elizabeth I. He lost an arm whilst capturing a Spanish ship during an expedition in 1590, but despite this, he continued on privateering, successfully blockading Western Cuba the following year. In 1592, Newport captured the Portuguese carrack Madre de Deus (Mother of God), valued at £500,000. Sir Henry Morgan was a successful privateer. Operating out of Jamaica, he carried on a war against Spanish interests in the region, often using cunning tactics. His operation was prone to cruelty against those he captured, including torture to gain information about booty, and in one case using priests as human shields. Despite reproaches for some of his excesses, he was generally protected by Sir Thomas Modyford, the governor of Jamaica. He took an enormous amount of booty, as well as landing his privateers ashore and attacking land fortifications, including the sack of the city of Panama with only 1,400 crew.[22] Other British privateers of note include Fortunatus Wright, Edward Collier, Sir John Hawkins, his son Sir Richard Hawkins, Michael Geare, and Sir Christopher Myngs. Notable British colonial privateers in Nova Scotia include Alexander Godfrey of the brig Rover and Joseph Barss of the schooner Liverpool Packet. The latter schooner captured over 50 American vessels during the War of 1812. BermudiansThe English colony of Bermuda (or the Somers Isles), settled accidentally in 1609, was used as a base for English privateers from the time it officially became part of the territory of the Virginia Company in 1612, especially by ships belonging to Robert Rich, the Earl of Warwick, for whom Bermuda's Warwick Parish is named (the Warwick name had long been associated with commerce raiding, as exampled by the Newport Ship,[23] thought to have been taken from the Spanish by Warwick the Kingmaker in the 15th century).[24][25] Many Bermudians were employed as crew aboard privateers throughout the century, although the colony was primarily devoted to farming cash crops until turning from its failed agricultural economy to the sea after the 1684 dissolution of the Somers Isles Company (a spin-off of the Virginia Company, which had overseen the colony since 1615). With a total area of 54 square kilometres (21 sq mi) and lacking any natural resources other than the Bermuda cedar, the colonists applied themselves fully to the maritime trades, developing the speedy Bermuda sloop, which was well suited both to commerce and to commerce raiding. Bermudian merchant vessels turned to privateering at every opportunity in the 18th century, preying on the shipping of Spain, France, and other nations during a series of wars, including the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War (King William's War); the 1702 to 1713 Queen Anne's War;[26][27] the 1739 to 1748 War of Jenkins' Ear; the 1740 to 1748 War of the Austrian Succession (King George's War); the 1754 to 1763 Seven Years' War (known in the United States as the French and Indian War), this conflict was devastating for the colony's merchant fleet. Fifteen privateers operated from Bermuda during the war, but losses exceeded captures; the 1775 to 1783 American War of Independence; and the 1796 to 1808 Anglo-Spanish War.[28][29] By the middle of the 18th century, Bermuda was sending twice as many privateers to sea as any of the continental colonies. They typically left Bermuda with very large crews. This advantage in manpower was vital in overpowering the crews of larger vessels, which themselves often lacked sufficient crewmembers to put up a strong defence. The extra crewmen were also useful as prize crews for returning captured vessels. The Bahamas, which had been depopulated of its indigenous inhabitants by the Spanish, had been settled by England, beginning with the Eleutheran Adventurers, dissident Puritans driven out of Bermuda during the English Civil War. Spanish and French attacks destroyed New Providence in 1703, creating a stronghold for pirates, and it became a thorn in the side of British merchant trade through the area. In 1718, Britain appointed Woodes Rogers as Governor of the Bahamas, and sent him at the head of a force to reclaim the settlement. Before his arrival, however, the pirates had been forced to surrender by a force of Bermudian privateers who had been issued letters of marque by the Governor of Bermuda.  Bermuda was in de facto control of the Turks Islands, with their lucrative salt industry, from the late 17th century to the early 19th. The Bahamas made perpetual attempts to claim the Turks for itself. On several occasions, this involved seizing the vessels of Bermudian salt traders. A virtual state of war was said to exist between Bermudian and Bahamian vessels for much of the 18th century. When the Bermudian sloop Seaflower was seized by the Bahamians in 1701, the response of the Governor of Bermuda, Captain Benjamin Bennett, was to issue letters of marque to Bermudian vessels. In 1706, Spanish and French forces ousted the Bermudians but were driven out themselves three years later by the Bermudian privateer Captain Lewis Middleton. His ship, the Rose, attacked a Spanish and a French privateer holding a captive English vessel. Defeating the two enemy vessels, the Rose then cleared out the thirty-man garrison left by the Spanish and French.[30] Despite strong sentiments in support of the rebels, especially in the early stages, Bermudian privateers turned as aggressively on American shipping during the American War of Independence. The importance of privateering to the Bermudian economy had been increased not only by the loss of most of Bermuda's continental trade but also by the Palliser Act, which forbade Bermudian vessels from fishing the Grand Banks. Bermudian trade with the rebellious American colonies actually carried on throughout the war. Some historians credit the large number of Bermuda sloops (reckoned at over a thousand) built-in Bermuda as privateers and sold illegally to the Americans as enabling the rebellious colonies to win their independence.[31] Also, the Americans were dependent on Turks salt, and one hundred barrels of gunpowder were stolen from a Bermudian magazine and supplied to the rebels as orchestrated by Colonel Henry Tucker and Benjamin Franklin, and as requested by George Washington, in exchange for which the Continental Congress authorised the sale of supplies to Bermuda, which was dependent on American produce. The realities of this interdependence did nothing to dampen the enthusiasm with which Bermudian privateers turned on their erstwhile countrymen. An American naval captain, ordered to take his ship out of Boston Harbor to eliminate a pair of Bermudian privateering vessels that had been picking off vessels missed by the Royal Navy, returned frustrated, saying, "the Bermudians sailed their ships two feet for every one of ours".[32] Around 10,000 Bermudians emigrated in the years prior to American independence, mostly to the American colonies. Many Bermudians occupied prominent positions in American seaports, from where they continued their maritime trades (Bermudian merchants controlled much of the trade through ports like Charleston, South Carolina, and Bermudian shipbuilders influenced the development of American vessels, like the Chesapeake Bay schooner),[28][33][34] and in the Revolution they used their knowledge of Bermudians and of Bermuda, as well as their vessels, for the rebels' cause. In the 1777 Battle of Wreck Hill, brothers Charles and Francis Morgan, members of a large Bermudian enclave that had dominated Charleston, South Carolina and its environs since settlement,[35][36] captaining two sloops (the Fair American and the Experiment, respectively), carried out the only attack on Bermuda during the war. The target was a fort that guarded a little used passage through the encompassing reef line. After the soldiers manning the fort were forced to abandon it, they spiked its guns and fled themselves before reinforcements could arrive.[37]  When the Americans captured the Bermudian privateer Regulator, they discovered that virtually all of her crew were black slaves. Authorities in Boston offered these men their freedom, but all 70 elected to be treated as prisoners of war. Sent as such to New York on the sloop Duxbury, they seized the vessel and sailed it back to Bermuda.[38] One-hundred and thirty prizes were brought to Bermuda in the year between 4th day of April 1782 and the 4th day of April 1783 alone, including three by Royal Naval vessels and the remainder by privateers.[39] The War of 1812 saw an encore of Bermudian privateering, which had died out after the 1790s. The decline of Bermudian privateering was due partly to the buildup of the naval base in Bermuda, which reduced the Admiralty's reliance on privateers in the western Atlantic, and partly to successful American legal suits and claims for damages pressed against British privateers, a large portion of which were aimed squarely at the Bermudians.[35] During the course of the War of 1812, Bermudian privateers captured 298 ships, some 19% of the 1,593 vessels captured by British naval and privateering vessels between the Great Lakes and the West Indies.[40] Among the better known (native-born and immigrant) Bermudian privateers were Hezekiah Frith, Bridger Goodrich,[41] Henry Jennings, Thomas Hewetson,[42] and Thomas Tew. Providence Island colonyBermudians were also involved in privateering from the short-lived English colony on Isla de Providencia, off the coast of Nicaragua. This colony was initially settled largely via Bermuda, with about eighty Bermudians moved to Providence in 1631. Although it was intended that the colony be used to grow cash crops, its location in the heart of the Spanish controlled territory ensured that it quickly became a base for privateering. Bermuda-based privateer Daniel Elfrith, while on a privateering expedition with Captain Sussex Camock of the bark Somer Ilands (a rendering of "Somers Isles", the alternate name of the Islands of Bermuda commemorating Admiral Sir George Somers) in 1625, discovered two islands off the coast of Nicaragua, 80 kilometres (50 mi) apart from each other. Camock stayed with 30 of his men to explore one of the islands, San Andrés, while Elfrith took the Warwicke back to Bermuda bringing news of Providence Island. Bermuda Governor Bell wrote on behalf of Elfrith to Sir Nathaniel Rich, a businessman and cousin of the Earl of Warwick (the namesake of Warwick Parish), who presented a proposal for colonizing the island noting its strategic location "lying in the heart of the Indies & the mouth of the Spaniards". Elfrith was appointed admiral of the colony's military forces in 1631, remaining the overall military commander for over seven years. During this time, Elfrith served as a guide to other privateers and sea captains arriving in the Caribbean. Elfrith invited the well-known privateer Diego el Mulato to the island. Samuel Axe, one of the military leaders, also accepted letters of marque from the Dutch authorizing privateering. The Spanish did not hear of the Providence Island colony until 1635 when they captured some Englishmen in Portobelo, on the Isthmus of Panama. Francisco de Murga, Governor and Captain-General of Cartagena, dispatched Captain Gregorio de Castellar y Mantilla and engineer Juan de Somovilla Texada to destroy the colony. [43] The Spanish were repelled and forced to retreat "in haste and disorder".[44] After the attack, King Charles I of England issued letters of marque to the Providence Island Company on 21 December 1635 authorizing raids on the Spanish in retaliation for a raid that had destroyed the English colony on Tortuga earlier in 1635 (Tortuga had come under the protection of the Providence Island Company. In 1635 a Spanish fleet raided Tortuga. 195 colonists were hung and 39 prisoners and 30 slaves were captured). The company could in turn issue letters of marque to subcontracting privateers who used the island as a base, for a fee. This soon became an important source of profit. Thus the company made an agreement with the merchant Maurice Thompson under which Thompson could use the island as a base in return for 20% of the booty.[45] In March 1636 the Company dispatched Captain Robert Hunt on the Blessing to assume the governorship of what was now viewed as a base for privateering.[46] Depredations continued, leading to growing tension between England and Spain, which were still technically at peace. On 11 July 1640, the Spanish Ambassador in London complained again, saying he

Nathaniel Butler, formerly Governor of Bermuda, was the last full governor of Providence Island, replacing Robert Hunt in 1638. Butler returned to England in 1640, satisfied that the fortifications were adequate, deputizing the governorship to Captain Andrew Carter.[48] In 1640, don Melchor de Aguilera, Governor and Captain-General of Cartagena, resolved to remove the intolerable infestation of pirates on the island. Taking advantage of having infantry from Castile and Portugal wintering in his port, he dispatched six hundred armed Spaniards from the fleet and the presidio, and two hundred black and mulatto militiamen under the leadership of don Antonio Maldonado y Tejada, his Sergeant Major, in six small frigates and a galleon.[49] The troops were landed on the island, and a fierce fight ensued. The Spanish were forced to withdraw when a gale blew up and threatened their ships. Carter had the Spanish prisoners executed. When the Puritan leaders protested against this brutality, Carter sent four of them home in chains.[50] The Spanish acted decisively to avenge their defeat. General Francisco Díaz Pimienta was given orders by King Philip IV of Spain, and sailed from Cartagena to Providence with seven large ships, four pinnaces, 1,400 soldiers and 600 seamen, arriving on 19 May 1641. At first, Pimienta planned to attack the poorly defended east side, and the English rushed there to improvise defenses. With the winds against him, Pimienta changed plans and made for the main New Westminster harbor and launched his attack on 24 May. He held back his large ships to avoid damage, and used the pinnaces to attack the forts. The Spanish troops quickly gained control, and once the forts saw the Spanish flag flying over the governor's house, they began negotiations for surrender.[51] On 25 May 1641, Pimienta formally took possession and celebrated mass in the church. The Spanish took sixty guns, and captured the 350 settlers who remained on the island – others had escaped to the Mosquito Coast. They took the prisoners to Cartagena.[52] The women and children were given a passage back to England. The Spanish found gold, indigo, cochineal and six hundred black slaves on the island, worth a total of 500,000 ducats, some of the accumulated booty from the raids on Spanish ships.[53] Rather than destroy the defenses, as instructed, Pimienta left a small garrison of 150 men to hold the island and prevent occupation by the Dutch.[52] Later that year, Captain John Humphrey, who had been chosen to succeed Captain Butler as governor, arrived with a large group of dissatisfied settlers from New England. He found the Spanish occupying the islands, and sailed away.[54] Pimienta's decision to occupy the island was approved in 1643 and he was made a knight of the Order of Santiago.[52] Spain and its colonies  When Spain issued a decree blocking foreign countries from trading, selling or buying merchandise in its Caribbean colonies, the entire region became engulfed in a power struggle among the naval superpowers.[55] The newly independent United States later became involved in this scenario, complicating the conflict.[55] As a consequence, Spain increased the issuing of privateering contracts.[55] These contracts allowed an income option to the inhabitants of these colonies that were not related to the Spanish conquistadores. The most well-known privateer corsairs of the eighteenth century in the Spanish colonies were Miguel Enríquez of Puerto Rico and José Campuzano-Polanco of Santo Domingo.[56] Miguel Enríquez was a Puerto Rican mulatto who abandoned his work as a shoemaker to work as a privateer. Such was the success of Enríquez, that he became one of the wealthiest men in the New World. His fleet was composed of approx. 300 different ships during a career that spanned 35 years, becoming a military asset and reportedly outperforming the efficiency of the Armada de Barlovento. Enríquez was knighted and received the title of Don from Philip V, something unheard of due to his ethnic and social background. One of the most famous privateers from Spain was Amaro Pargo. France Corsairs (French: corsaire) were privateers, authorized to conduct raids on shipping of a nation at war with France, on behalf of the French Crown. Seized vessels and cargo were sold at auction, with the corsair captain entitled to a portion of the proceeds. Although not French Navy personnel, corsairs were considered legitimate combatants in France (and allied nations), provided the commanding officer of the vessel was in possession of a valid Letter of Marque (fr. Lettre de Marque or Lettre de Course), and the officers and crew conducted themselves according to contemporary admiralty law. By acting on behalf of the French Crown, if captured by the enemy, they could claim treatment as prisoners of war, instead of being considered pirates. Because corsairs gained a swashbuckling reputation, the word "corsair" is also used generically as a more romantic or flamboyant way of referring to privateers, or even to pirates. The Barbary pirates of North Africa as well as Ottomans were sometimes called "Turkish corsairs". MaltaCorsairing (Italian: corso) was an important aspect of Malta's economy when the island was ruled by the Order of St. John, although the practice had begun earlier. Corsairs sailed on privately owned ships on behalf of the Grand Master of the Order, and were authorized to attack Muslim ships, usually merchant ships from the Ottoman Empire. The corsairs included knights of the Order, native Maltese people, as well as foreigners. When they captured a ship, the goods were sold and the crew and passengers were ransomed or enslaved, and the Order took a percentage of the value of the booty.[57] Corsairing remained common until the end of the 18th century.[58] United StatesBritish Colonial period During King George's War, approximately 36,000 Americans served aboard privateers at one time or another.[59] During the Nine Years War, the French adopted a policy of strongly encouraging privateers, including the famous Jean Bart, to attack English and Dutch shipping. England lost roughly 4,000 merchant ships during the war.[59] In the following War of Spanish Succession, privateer attacks continued, Britain losing 3,250 merchant ships.[60] In the subsequent conflict, the War of Austrian Succession, the Royal Navy was able to concentrate more on defending British ships. Britain lost 3,238 merchantmen, a smaller fraction of her merchant marine than the enemy losses of 3,434.[59] While French losses were proportionally severe, the smaller but better protected Spanish trade suffered the least and it was Spanish privateers who enjoyed much of the best-allied plunder of British trade, particularly in the West Indies. American Revolutionary WarDuring the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress, and some state governments (on their own initiative), issued privateering licenses, authorizing "legal piracy", to merchant captains in an effort to take prizes from the British Navy and Tory (Loyalist) privateers. This was done due to the relatively small number of commissioned American naval vessels and the pressing need for prisoner exchange.  About 55,000 American seamen served aboard the privateers.[61] They quickly sold their prizes, dividing their profits with the financier (persons or company) and the state (colony). Long Island Sound became a hornets' nest of privateering activity during the American Revolution (1775–1783), as most transports to and from New York went through the Sound. New London, Connecticut was a chief privateering port for the American colonies, leading to the British Navy blockading it in 1778–1779. Chief financiers of privateering included Thomas & Nathaniel Shaw of New London and John McCurdy of Lyme. In the months before the British raid on New London and Groton, a New London privateer took Hannah in what is regarded as the largest prize taken by any American privateer during the war. Retribution was likely part of Gov. Clinton's (NY) motivation for Arnold's Raid, as the Hannah had carried many of his most cherished items. American privateers are thought to have seized up to 300 British ships during the war. The British ship Jack was captured and turned into an American privateer, only to be captured again by the British in the naval battle off Halifax, Nova Scotia. American privateers not only fought naval battles but also raided numerous communities in British colonies, such as the Raid on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia (1782). The United States Constitution authorized the U.S. Congress to grant letters of marque and reprisal. Between the end of the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, less than 30 years, Britain, France, Naples, the Barbary States, Spain, and the Netherlands seized approximately 2,500 American ships.[62] Payments in ransom and tribute to the Barbary states amounted to 20% of United States government annual revenues in 1800[63] and would lead the United States to fight the Barbary states in the First Barbary War and Second Barbary Wars. War of 1812During the War of 1812, both the British and the American governments used privateers, and the established system was very similar.[64] U.S. Congress declared

President Madison issued 500 letters of marque authorizing privateers. Overall some 200 of the ships took prizes. The cost of buying and fitting of a large privateer was about $40,000 and prizes could net $100,000.[66] Captain Thomas Boyle was one of the famous and successful American privateers. He commanded the Baltimore schooner Comet and then later in the war the Baltimore clipper Chasseur. He captured over 50 British merchant ships during the war. One source[67] estimated a total damage to the British merchant navy from Chasseur's 1813-1815 activities at one and a half million dollars. In total, the Baltimore privateer fleet of 122 ships sunk or seized 500 British ships with an estimated value of $16 million, which accounts about one-third of all the value of all prizes taken over the course of the whole war.[68]  On April 8, 1814, the British attacked Essex, Connecticut, and burned the ships in the harbor, due to the construction there of a number of privateers. This was the greatest financial loss of the entire War of 1812 suffered by the Americans. However, the private fleet of James De Wolf, which sailed under the flag of the American government in 1812, was most likely a key factor in the naval campaign of the war. De Wolf's ship, the Yankee, was possibly the most financially successful ship of the war. Privateers proved to be far more successful than their US Navy counterparts, claiming three-quarters of the 1600 British merchant ships taken during the war (although a third of these were recaptured prior to making landfall). One of the more successful of these ships was the Prince de Neufchatel, which once captured nine British prizes in swift succession in the English Channel.[citation needed] Jean Lafitte and his privateers aided US General Andrew Jackson in the defeat of the British in the Battle of New Orleans in order to receive full pardons for their previous crimes.[69][70][71][72][73] Jackson formally requested clemency for Lafitte and the men who had served under him, and the US government granted them all a full pardon on February 6, 1815.[74][75] However, many of the ships captured by the Americans were recaptured by the Royal Navy. British convoy systems honed during the Napoleonic Wars limited losses to singleton ships, and the effective blockade of American and continental ports prevented captured ships being taken in for sale. This ultimately led to orders forbidding US privateers from attempting to bring their prizes in to port, with captured ships instead having to be burnt. Over 200 American privateer ships were captured by the Royal Navy, many of which were turned on their former owners and used by the British blockading forces. Nonetheless, during the War of 1812 the privateers "swept out from America's coasts, capturing and sinking as many as 2,500 British ships and doing approximately $40 million worth of damage to the British economy."[64] 1856 Declaration of ParisThe US was not one of the initial signatories of the 1856 Declaration of Paris which outlawed privateering, and the Confederate Constitution authorized use of privateers. However, the US did offer to adopt the terms of the Declaration during the American Civil War, when the Confederates sent several privateers to sea before putting their main effort in the more effective commissioned raiders. American Civil War During the American Civil War privateering took on several forms, including blockade running while privateering, in general, occurred in the interests of both the North and the South. Letters of marque would often be issued to private shipping companies and other private owners of ships, authorizing them to engage vessels deemed to be unfriendly to the issuing government. Crews of ships were awarded the cargo and other prizes aboard any captured vessel as an incentive to search far and wide for ships attempting to supply the Confederacy, or aid the Union, as the case may be. During the Civil War Confederate President Jefferson Davis issued letters of marque to anyone who would employ their ship to either attack Union shipping or bring badly needed supplies through the Union blockade into southern ports.[76] Most of the supplies brought into the Confederacy were carried aboard privately owned vessels. When word came about that the Confederacy was willing to pay almost any price for military supplies, various interested parties designed and built specially designed lightweight seagoing steamers, blockade runners specifically designed and built to outrun Union ships on blockade patrol.[77] Neither the United States nor Spain authorized privateers in their war in 1898.[78] Latin America Warships were recruited by the insurgent governments during Spanish American wars of independence to destroy Spanish trade, and capture Spanish Merchant vessels. The private armed vessels came largely from the United States. Seamen from Britain, the United States, and France often manned these ships. Computer hackersModern-day computer hackers have been compared to the privateers of by-gone days.[79] These criminals hold computer systems hostage, demanding large payments from victims to restore access to their own computer systems and data.[80] Furthermore, recent ransomware attacks on industries, including energy, food, and transportation, have been blamed on criminal organizations based in or near a state actor – possibly with the country's knowledge and approval.[81] Cyber theft and ransomware attacks are now the fastest-growing crimes in the United States.[82] Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies facilitate the extortion of huge ransoms from large companies, hospitals and city governments with little or no chance of being caught.[83] See also

References

Bibliography

Further reading

Primary sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Privateers.

|