|

Pieter Nuyts

Pieter Nuyts or Nuijts (1598 – 11 December 1655) was a Dutch explorer, diplomat and politician. He was part of a landmark expedition of the Dutch East India Company in 1626–27 which mapped the southern coast of Australia. He became the Dutch ambassador to Japan in 1627, and he was appointed governor of Formosa in the same year. Later he became a controversial figure because of his disastrous handling of official duties, coupled with rumours about private indiscretions. He was disgraced, fined and imprisoned, before being made a scapegoat to ease strained Dutch relations with the Japanese. He returned to the Dutch Republic in 1637, where he became the mayor of Hulster Ambacht and of Hulst. He is chiefly remembered today in the place names of various points along the southern Australian coast, named for him after his voyage of 1626–27. During the early 20th century, he was vilified in Japanese school textbooks in Taiwan as an example of a "typical arrogant western bully". Early lifePieter Nuyts was born in 1598 in the town of Middelburg in Zeeland, Dutch Republic to Laurens Nuyts, a merchant, and his wife Elisabeth Walraents, wealthy Protestant immigrants from Antwerp.[1] After studying at the University of Leiden and gaining a doctorate in philosophy, he returned to Middelburg to work in his father's trading company.  In 1613, Pieter Nuyts, who was staying in Leiden with the famous Orientalist Erpenius, is known to have met with the Moroccan envoy in the Low Countries Al-Hajari.[2] Al-Hajari wrote for him an entry in Pieter's Album Amicorum stating:

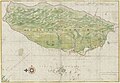

In 1620, Pieter married Cornelia Jacot, also a child of Antwerp émigrés, who was to bear four of his children—Laurens (born around 1622), Pieter (1624) and the twins Anna Cornelia and Elisabeth (1626). In 1626 he entered service with the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and was seen as one of their rising stars.[1] Australian expedition On 11 May 1626 the VOC ship 't Gulden Zeepaert (The Golden Seahorse) departed from Amsterdam with Nuyts and his eldest son Laurens aboard.[3] Deviating from the standard route to the VOC's East Asian Batavia headquarters, the ship continued east and mapped around 1,500 km of the southern coast of Australia from Albany, Western Australia to Ceduna, South Australia. The captain of the ship, François Thijssen, named the region ′t Landt van Pieter Nuyts (Pieter Nuyts' Land) after Nuyts, who was the highest-ranking official on the ship.[4] Today several areas in the state of South Australia still bear his name, such as Nuyts Reef, Cape Nuyts and the Nuyts Archipelago; names given by the British navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders.[4] Later Nuytsia floribunda, the Western Australian Christmas Tree, was also named for him.[5] Ambassador to JapanOn 10 May 1627, a month after completing his Australian voyage, Nuyts was simultaneously appointed both governor of Formosa (Taiwan) and ambassador to Japan for the Dutch East India Company, travelling in this capacity to the court of the shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu, ruler of Japan.[6] At the same time Hamada Yahei, a Japanese trader based in Nagasaki with frequent business in Formosa, had taken a group of sixteen native Formosans to Japan and had them pose as rulers of Formosa. His plan was to have the Formosans grant sovereignty over Taiwan to the shōgun, while Nuyts was in Japan to assert rival Dutch claims on the island. Both embassies were refused an audience with the shōgun (the Dutch failure being variously attributed to Nuyts's "haughty demeanour and the antics of his travel companions" and "Hamada's machinations at the court").[1][6] Governor of Formosa On returning from his unsuccessful mission to Japan, Nuyts took up his position as the third governor of Formosa, with his residence in Fort Zeelandia in Tayouan (modern-day Anping). One of his early aims was to force an opening for the Dutch to trade in China — something which had eluded them since they arrived in East Asia in the early 17th century. To further this goal, he took the Chinese trade negotiator Zheng Zhilong hostage and refused to release him until he agreed to give the Dutch trading privileges.[6] More than thirty years later it was to be Zheng's son Koxinga who ended the reign of the Dutch on Formosa.  Nuyts acquired some notoriety while governor for apparently taking native women to his bed, and having a translator hide under the bed to interpret his pillow-talk.[4] He was also accused of profiting from private trade, something which was forbidden under company rules.[7] Some sources claim that he officially married a native Formosan woman during this time,[4] but as he was still legally married to his first wife Cornelia, this seems unlikely.[6] His handling of relations with the natives of Formosa too was a cause for concern, with the residents of Sinkan contrasting his harsh treatment with the "generous hospitality of the Japanese". Nuyts had a low opinion of the natives, writing that they were "a simple, ignorant people, who know neither good nor evil".[8] In 1629 he narrowly escaped death when after being feted at the aboriginal village of Mattau, the locals took advantage of the relaxed and convivial atmosphere to slaughter sixty off-guard Dutch soldiers—Nuyts was spared by having left early to return to Zeelandia.[7] This incident was later used as a justification for the Pacification Campaign of 1635–36.[9] It was during Nuyts' tenure as governor that the Spanish established their presence on Formosa in 1629. He was greatly concerned by this development, and wrote to Batavia urgently requesting an expedition to dislodge the Spanish from their strongholds in Tamsuy and Kelang. In his letter he stressed the potential for the Spanish to interfere with Dutch activities and the trade benefits the Dutch could gain by taking the north of the island. The colonial authorities ignored his request, and took no action against the Spanish until 1641.[10] Hostage crisis The already troubled relations with Japanese merchants in Tayouan took a turn for the worse in 1628 when tensions boiled over. The merchants, who had been trading in Taiwan long before the Dutch colony was established, refused to pay Dutch tolls levied for conducting business in the area, which they saw as unfair. Nuyts exacted revenge on the same Hamada Yahei who he blamed for causing the failure of the Japanese embassy by impounding his ships and weapons until the tolls were paid.[11][12][13] However, the Japanese were still not inclined to pay taxes, and the affair came to a head when Hamada took Nuyts hostage at knifepoint in his own office. Hamada's demands were for the return of their ships and property, and for safe passage to return to Japan.[11] These requests were granted by the Council of Formosa (the ruling body of Dutch Formosa), and Nuyts' son Laurens was taken back to Japan as one of six Dutch hostages. Laurens died in Omura prison on 29 December 1631.[6] During the Japanese era in Taiwan (1895–1945), school history textbooks retold the hostage-taking as the Nuyts Incident (ヌィッチ事件, noitsu jiken)[citation needed], portraying the Dutchman as a "typical arrogant western bully who slighted Japanese trading rights and trod on the rights of the native inhabitants".[11] Extradition to JapanThe Dutch were very keen to resume the lucrative trade with Japan which had been choked off in the wake of the dispute between Nuyts and Hamada at the behest of the Japanese authorities in Edo.[6] All their overtures to the Japanese court failed, until they decided to extradite Pieter Nuyts to Japan for the shōgun to punish him as he saw fit. This was an unprecedented step, and was representative of both the extreme official displeasure with Nuyts in the Dutch hierarchy and the strong desire to recommence Japanese trade.[14][15] It also demonstrates the relative weakness of the Dutch when confronted by powerful East Asian states such as Japan, and recent historiography has suggested that the Dutch relied on the mercy of these states to maintain their position.[16] A measure of the upset he caused to the Dutch authorities can be gauged by the contents of a letter from VOC Governor-General Anthony van Diemen to VOC headquarters in Amsterdam in 1636, expressing his concern about plans to send a highly paid lawyer to Batavia to draw up a legal code:

Nuyts was held under house arrest by the Japanese from 1632 until 1636, when he was released and sent back to Batavia.[17] During this period he passed the time by mining his collection of classical Latin texts by writers such as Cicero, Seneca, and Tacitus to write treatises on subjects such as the elephant and the Nile Delta, exercises which were designed to display rhetorical flair and high style. He also further annoyed Dutch authorities by spending lavish sums on clothing and food, things for which the VOC had to foot the bill.[15] Nuyts was released from captivity in 1636, most likely due to the efforts of François Caron, who knew Nuyts from serving as his interpreter during the unsuccessful Japanese embassy of 1627.[18] On returning from Japan, Nuyts was fined by the VOC, before being dishonorably dismissed from the company and sent back to the Netherlands.[15] Return to the Dutch Republic On returning to his home country he first went back to his city of birth Middelburg, before starting a career as a local administrator in Zeelandic Flanders, and settling in Hulst shortly after the town had been wrested from the Spanish in 1645.[19] He eventually rose to be three times mayor of Hulster Ambacht and twice mayor of Hulst.[4] Thanks to powerful allies in the Middelburg chamber of the VOC he was able to successfully appeal for the cancellation of the fines placed on him, and the money was returned.[17] In 1640 he married Anna van Driel, who died that same year while giving birth to Nuyts' third son, also called Pieter. In 1649 he married his third (or perhaps fourth) and final wife, Agnes Granier, who was to outlive him.[4] DeathNuyts died on 11 December 1655 and was buried in a churchyard in Hulst.[19] The tombstone remained until 1983, when it was destroyed during renovations of the church.[19] After his funeral it was discovered that he had collected more taxes from his estates than he had handed over to the authorities; his son Pieter eventually repaid his father's debts.[4] It was the younger Pieter who also arranged the posthumous publication of his father's treatise Lof des Elephants, in 1670 — a single known copy of which still exists, in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague.[1] Bibliography

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||