|

Peter Blume

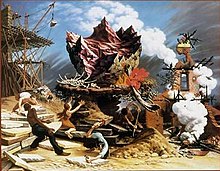

Peter Blume (27 October 1906 – 30 November 1992) was an American painter and sculptor. His work contained elements of folk art, Precisionism, Parisian Purism, Cubism, and Surrealism.[1] BiographyBlume, born in Smarhon, Russian Empire to a Jewish family,[2][failed verification] emigrated with his family to New York City in 1912; the family settled in Brooklyn.[1] He studied art at the Educational Alliance, the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, and the Art Students League of New York, establishing his own studio by 1926.[3] He trained with Raphael Soyer and Isaac Soyer, exhibited with Charles Daniel, and was patronized by the Rockefeller family.[4] Blume married Grace Douglas in 1931; they had no surviving children.[1] In 1948, Blume was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member, and became a full member in 1956. WorksAn admirer of Renaissance technique, Blume worked by drawing and making cartoons before putting his work on canvas. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1932 and spent a year in Italy. His first major recognition came in 1934 with a first prize for South of Scranton at a Carnegie Institute International Exhibition. The painting was inspired by a trip across Pennsylvania in an old car that required frequent repair.[1] Eternal City (1934–1937) was politically charged, portraying Benito Mussolini as a jack-in-the-box emerging from the Colosseum; as a one-man, one-painting exhibition, it excited considerable attention from critics and audiences.[1][5] This painting was inspired by Blume's trip to Italy which he took as a Guggenheim Fellow in 1932.[6] After the trip from Rome, it took Blume 5 years to create this piece of work. In 1943 when Mussolini was deposed from power, the Museum of Modern Art purchased the artwork for its permanent collection within that same week.[7] Blume worked for the Section of Painting and Sculpture of the U.S. Treasury Department, painting at least two post office murals, in Geneva, New York, and Canonsburg, Pennsylvania.[8] Blume's works often portrayed destruction and restoration simultaneously.[1] Stones and girders made frequent appearances; The Rock (1944–1948), today in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, was interpreted by its viewers as symbolizing renewal in the wake of World War II. Recollection of the Flood (1969) depicted the victims of the 1966 Flood of the River Arno in Florence along with restorers at work. The Metamorphoses (1979) invoked the Greek legend of Deucalion and Pyrrha, who repopulated the earth after a deluge.[1] Gallery

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||