|

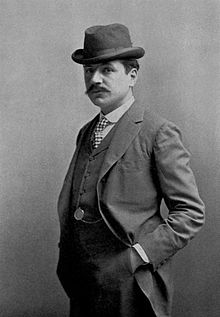

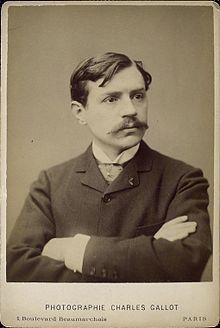

Paul Bourget

Paul Charles Joseph Bourget (French: [buʁʒɛ]; 2 September 1852 – 25 December 1935) was a French poet, novelist[1][2] and critic.[3] He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature five times.[4] Paul Bourget was born in Amiens, France. He initially abandoned Catholicism but eventually returned to it in the late 19th century. Bourget is known for his psychological and moralistic novels that often portrayed the complex emotions of women and the ideas, passions, and failures of young men in France. Some of his notable works include Le Disciple (1889), a bestseller that explored the consequences of materialism and positivism, and other novels such as Cruelle Enigme (1885), André Cornelis (1886), and Mensonges (1887). He was admitted to the Académie Française in 1894 and was promoted to be an officer of the Légion d'honneur in 1895. Bourget's early career was marked by volumes of verse, but he later found success in literary journalism, and his critical works such as Sensations d'Italie (1891) are highly regarded. Though his novels were widely popular in his time, they have since been largely forgotten by the general reading public. Nonetheless, Bourget remains an important figure in French literature for his psychological and moralistic approach to fiction, and his influence can be seen in the works of several composers, including Claude Debussy, who set some of Bourget's poems to music. LifePaul Bourget was born in Amiens in the Somme département of Picardy, France. His father, a professor of mathematics, was later appointed to a post in the college at Clermont-Ferrand, where Bourget received his early education. He afterwards studied at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand and at the École des Hautes Études. Between 1872 and 1876, he produced a volume of verse, Au Bord de la Mer, which was followed by others, the last, Les Aveux, appearing in 1882.[5] Meanwhile, he was making a name in literary journalism and in 1883 he published Essais de Psychologie Contemporaine, studies of eminent writers first printed in the Nouvelle Revue, and now brought together. In 1884 Bourget paid a long visit to Britain, where he wrote his first published story (L'Irréparable). Cruelle Enigme followed in 1885; then André Cornelis (1886) and Mensonges (1887) - inspired by Octave Mirbeau's life - were received with much favour.[6] Bourget, who had abandoned Catholicism in 1867, began a gradual return to it in 1889, fully converting only in 1901. In 1893, in an interview he gave in America, he spoke about his changed views: "For many years I, like most young men in modern cities, was content to drift along in agnosticism, but I was brought to my senses at last by the growing realization that...the life of a man who simply said 'I don't know, and not knowing I do the thing that pleases me,' was not only empty in itself and full of disappointment and suffering, but was a positive influence for evil upon the lives of others." On the other hand, "those men and women who follow the teachings of the church are in a great measure protected from the moral disasters which...almost invariably follow when men and women allow themselves to be guided and swayed by their senses, passions and weaknesses."[7] These were the themes of his novel Le Disciple (1889), which he wrote, as he says in his American interview, just after abandoning his "drifting and comfortable belief in agnosticism". It is the story of philosopher Adrien Sixte, whose advocacy of materialism and positivism wields a terrible influence over an admiring but unstable student, Robert Geslon, whose actions, in turn, lead to the tragic death of a young woman.[8] Le Disciple caused a stir in France and became a bestseller. Exemplifying the novelist's graver side, it was one of William Gladstone's favourite books.[7] John Cowper Powys listed Le Disciple at number 33 in his One Hundred Best Books.[9]  Études et portraits, first published in 1888, contains impressions of Bourget's stay in England and Ireland—especially reminiscences of the months which he spent at Oxford and in 1891 Sensations d'Italie, notes of a tour in that country, revealed a fresh phase of his powers; and Outre-Mer (1895), a book in two volumes, is his critical journal of a visit to the United States in 1893. Also in 1891 appeared the novel Coeur de Femme, and Nouveaux Pastels, "types" of the characters of men, the sequel to a similar gallery of female types (Pastels, 1890). His later novels include La Terre Promise (1892); Cosmopolis (1892), a psychological novel with Rome as a background; Une Idylle tragique (1896); La Duchesse bleue (1897); Le Fantôme (1901); Les Deux Sœurs (1905); and some volumes of shorter stories—Complications Sentimentales (1896), Drames de famille (1898), and Un Homme d'Affaires (1900). L'Etape (1902) was a study of the inability of a family raised too rapidly from the peasant class to adapt itself to new conditions. This study of contemporary manners was followed by Un Divorce (1904), a defence of the Roman Catholic position that divorce is a violation of natural laws. He was admitted to the Académie Française in 1894, and in 1895 was promoted to be an officer of the Légion d'honneur, having received the decoration of the order ten years before.[6] Several new novels were to follow, including La Vie Passe (1910), Le Sens de la Mort (1915), Lazarine (1917), Némésis (1918), and Laurence Albani (1920), as well as three volumes of short stories and plays, La Barricade (1910) and Le Tribun (1912). He wrote two other plays, Un Cas de Conscience (1910) and La Crise (1912), in collaboration with others. A volume of his critical studies appeared in 1912, and another set of travel sketches, Le Démon du Midi, in 1914.[10] On 16 March 1914, he was present in the offices of the newspaper Le Figaro when the newspaper's editor, his friend Gaston Calmette, was shot and killed by Henriette Caillaux, the wife of a former Prime Minister of France. Her subsequent trial caused an enormous scandal at the time.[11]  He was a contributor to Le Visage de l'Italie, a 1929 book about Italy prefaced by Benito Mussolini.[12] Bourget died on Christmas Day 1935, aged 83, in Paris. Literary significance and criticismAs a writer of verse Bourget's poems, which were collected in two volumes (1885–1887), throw light upon his mature method and the later products of his art. It was in criticism that he excelled. Notable are the Sensations d'Italie (1891), and the various psychological studies.[6]  Bourget's reputation as a novelist is assured in some academic and intellectual circles but while they were widely popular in his time, his novels have long been largely forgotten by the general reading public. Impressed by the art of Henry Beyle (Stendhal), he struck out on a new course at a moment when the realist school was the vogue in French fiction. With Bourget, observation was mainly directed to the human character. At first his purpose seemed to be purely artistic, but when Le Disciple appeared, in 1889, the preface to that story revealed his moral enthusiasm. After that, he varied between his earlier and his later manner, but his work in general was more seriously conceived. He painted the intricate emotions of women, whether wronged, erring or actually vicious; and he described the ideas, passions and failures of the young men of France. One of his poems was the inspiration for an art song by Claude Debussy titled Beau Soir. Other settings by Debussy of poems by Bourget include 'Romance' and 'Les Cloches'. Works

In English translation

Selected articles

References

Further reading

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Paul Bourget. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paul Bourget.

|

||||||||||||||||||||