|

Orcus (dwarf planet)

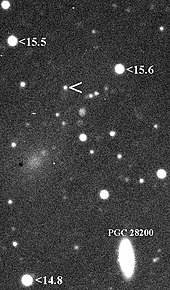

Orcus (minor-planet designation: 90482 Orcus) is a dwarf planet located in the Kuiper belt, with one large moon, Vanth.[7] It has an estimated diameter of 870 to 960 km (540 to 600 mi), comparable to the Inner Solar System dwarf planet Ceres. The surface of Orcus is relatively bright with albedo reaching 23 percent, neutral in color, and rich in water ice. The ice is predominantly in crystalline form, which may be related to past cryovolcanic activity. Other compounds like methane or ammonia may also be present on its surface. Orcus was discovered by American astronomers Michael Brown, Chad Trujillo, and David Rabinowitz on 17 February 2004. Orcus is a plutino, a trans-Neptunian object that is locked in a 2:3 orbital resonance with the ice giant Neptune, making two revolutions around the Sun to every three of Neptune's.[5] This is much like Pluto, except that the phase of Orcus's orbit is opposite to Pluto's: Orcus is at aphelion (most recently in 2019) around when Pluto is at perihelion (most recently in 1989) and vice versa.[17] Orcus is the second-largest known plutino, after Pluto itself. The perihelion of Orcus's orbit is around 120° from that of Pluto, while the eccentricities and inclinations are similar. Because of these similarities and contrasts, along with its large moon Vanth that can be compared to Pluto's large moon Charon, Orcus has been dubbed the "anti-Pluto."[18] This was a major consideration in selecting its name, as the deity Orcus was the Roman/Etruscan equivalent of the Roman/Greek Pluto.[18] HistoryDiscovery Orcus was discovered on 17 February 2004, by American astronomers Michael Brown of Caltech, Chad Trujillo of the Gemini Observatory, and David Rabinowitz of Yale University. Precovery images taken by the Palomar Observatory as early as 8 November 1951 were later obtained from the Digitized Sky Survey.[2] Name and symbolThe minor planet Orcus was named after one of the Roman gods of the underworld, Orcus. While Pluto (of Greek origin) was the ruler of the underworld, Orcus (of Etruscan origin) was a punisher of the condemned. The name was published by the Minor Planet Center on 26 November 2004 (M.P.C. 53177).[20] Under the guidelines of the International Astronomical Union's (IAU) naming conventions, objects with a similar size and orbit to that of Pluto are named after underworld deities. Accordingly, the discoverers suggested naming the object after Orcus, the Etruscan god of the underworld and punisher of broken oaths. The name was also a private reference to the homonymous Orcas Island, where Brown's wife had lived as a child and that they visit frequently.[21] On 30 March 2005, Orcus's moon, Vanth, was named after a winged female entity, Vanth, of the Etruscan underworld. She could be present at the moment of death, and frequently acted as a psychopomp, a guide of the deceased to the underworld.[22] The usage of planetary symbols is no longer recommended in astronomy, so Orcus never received a symbol in the astronomical literature. A symbol ⟨ Orbit and rotationOrcus is in a 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune, having an orbital period of 245 years,[5][1] and is classified as a plutino.[2] Its orbit is moderately inclined at 20.6° to the ecliptic.[1] Orcus's orbit is similar to Pluto's (both have perihelia above the ecliptic), but is oriented differently. Although at one point its orbit approaches that of Neptune, the resonance between the two bodies means that Orcus itself is always a great distance away from Neptune (there is always an angular separation of over 60° between them). Over a 14,000-year period, Orcus stays more than 18 AU from Neptune.[17] Because their mutual resonance with Neptune constrains Orcus and Pluto to remain in opposite phases of their otherwise very similar motions, Orcus is sometimes described as the "anti-Pluto".[18] Orcus last reached its aphelion (farthest distance from the Sun) in 2019 and will come to perihelion (closest distance to the Sun) around 10 January 2143.[9] Simulations by the Deep Ecliptic Survey show that over the next 10 million years Orcus may acquire a perihelion distance (qmin) as small as 27.8 AU.[5] The rotation period of Orcus is uncertain, as different photometric surveys have produced different results. Some show low amplitude variations with periods ranging from 7 to 21 hours, whereas others show no variability.[26] The rotational axis of Orcus probably coincides with the orbital axis of its moon, Vanth. This means that Orcus is currently viewed pole-on, which could explain the near absence of any rotational modulation of its brightness.[26][27] Astronomer José Luis Ortiz and colleagues have derived a possible rotation period of about 10.5 hours, assuming that Orcus is not tidally locked with Vanth.[27] If, however, the primary is tidally locked with the satellite, the rotational period would coincide with the 9.7-day orbital period of Vanth.[27] Physical characteristicsSize and magnitude  The absolute magnitude of Orcus is approximately 2.3.[11] The detection of Orcus by the Spitzer Space Telescope in the far infrared[28] and by Herschel Space Telescope in submillimeter estimates its diameter at 958.4 km (595.5 mi), with an uncertainty of 22.9 km (14.2 mi).[11] Orcus appears to have an albedo of about 21–25%,[11] which may be typical of trans-Neptunian objects approaching the 1,000 km (620 mi) diameter range.[29] The magnitude and size estimates were made under the assumption that Orcus is a singular object. The presence of a relatively large satellite, Vanth, may change them considerably. The absolute magnitude of Vanth is estimated at 4.88, which means that it is about 1/11 as bright as Orcus itself.[16] The ALMA submillimeter measurements taken in 2016 showed that Vanth has a relatively large size of 475 km (295 mi) with an albedo of about 8 percent while Orcus's has a slightly smaller size of 910 km (570 mi).[10] Using a stellar occultation by Vanth in 2017, Vanth's diameter has been determined to be 442.5 km (275.0 mi), with an uncertainty of 10.2 km (6.3 mi).[30] Michael Brown's website lists Orcus as a dwarf planet with "near certainty",[31] Tancredi concludes that it is one,[32] and is massive enough to be considered one under the 2006 draft proposal of the IAU,[33] but the IAU has not formally recognized it as such.[34][35] Mass and densityOrcus and Vanth are known to constitute a binary system. The mass of the system has been estimated to be (6.348±0.019)×1020 kg,[7] approximately equal to that of the Saturnian moon Tethys (6.175×1020 kg).[36] The mass of the Orcus system is about 3.8 percent that of Eris, the most massive known dwarf planet (1.66×1022 kg).[16][37] The ratio of the mass of Vanth to that of Orcus was measured astrometrically with the ALMA submillimeter telescope and is 0.16±0.02 with Vanth containing 13.7%±1.3% of the total system mass. This also means that the densities of both bodies are about the same at ~1.5 g/cm3.[12] Spectra and surfaceThe first spectroscopic observations in 2004 showed that the visible spectrum of Orcus is flat (neutral in color) and featureless, whereas in the near-infrared there were moderately strong water absorption bands at 1.5 and 2.0 μm.[38] The neutral visible spectrum and strong water absorption bands of Orcus showed that Orcus appeared different from other trans-Neptunian objects, which typically have a red visible spectrum and often featureless infrared spectra.[38] Further infrared observations in 2004 by the European Southern Observatory and the Gemini telescope gave results consistent with mixtures of water ice and carbonaceous compounds, such as tholins.[14] The water and methane ices can cover no more than 50 percent and 30 percent of the surface, respectively.[39] This means the proportion of ice on the surface is less than on Charon, but similar to that on Triton.[39] Later in 2008–2010 new infrared spectroscopic observations with a higher signal-to-noise ratio revealed additional spectral features. Among them is a deep water ice absorption band at 1.65 μm, which is evidence of the crystalline water ice on the surface of Orcus, and a new absorption band at 2.22 μm. The origin of the latter feature is not completely clear. It can be caused either by ammonia/ammonium dissolved in the water ice or by methane/ethane ices.[13] The radiative transfer modeling showed that a mixture of water ice, tholins (as a darkening agent), ethane ice, and ammonium ion (NH4+) provides the best match to the spectra, whereas a combination of water ice, tholins, methane ice and ammonia hydrate gives a slightly inferior result. On the other hand, a mixture of only ammonia hydrate, tholins and water ice failed to provide a satisfactory match.[26] As of 2010, the only reliably identified compounds on the surface of Orcus are crystalline water ice and, possibly, dark tholins. A firm identification of ammonia, methane, and other hydrocarbons requires a better infrared spectra.[26] Orcus sits at the threshold for trans-Neptunian objects massive enough to retain volatiles such as methane on the surface.[26] The reflectance spectrum of Orcus shows the deepest water-ice absorption bands of any Kuiper belt object that is not associated with the Haumea collisional family.[16] The large icy satellites of Uranus have infrared spectra quite similar to that of Orcus.[16] Among other trans-Neptunian objects, the large plutino 2003 AZ84 and Pluto's moon Charon both have similar surface spectra to Orcus,[13] with flat, featureless visible spectra and moderately strong water ice absorption bands in the near-infrared.[26] CryovolcanismCrystalline water ice on the surfaces of trans-Neptunian objects should be completely amorphized by the galactic and Solar radiation in about 10 million years.[13] Thus the presence of crystalline water ice, and possibly ammonia ice, may indicate that a renewal mechanism was active in the past on the surface of Orcus.[13] Ammonia so far has not been detected on any trans-Neptunian object or icy satellite of the outer planets other than Miranda.[13] The 1.65 μm band on Orcus is broad and deep (12%), as on Charon, Quaoar, Haumea, and icy satellites of the giant planets.[13] Some calculations indicate that cryovolcanism, which is considered one of the possible renewal mechanisms, may indeed be possible for trans-Neptunian objects larger than about 1,000 km (620 mi).[26] Orcus may have experienced at least one such episode in the past, which turned the amorphous water ice on its surface into crystalline. The preferred type of volcanism may have been explosive aqueous volcanism driven by an explosive dissolution of methane from water–ammonia melts.[26] Satellite Orcus has one known moon, Vanth (full designation (90482) Orcus I Vanth). It was discovered by Michael Brown and T.-A. Suer using discovery images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope on 13 November 2005.[40] The discovery was announced in an IAU Circular notice published on 22 February 2007.[41] A spatially resolved submillimeter imaging of Orcus–Vanth system in 2016 showed that Vanth has a relatively large size of 475 km (295 mi), with an uncertainty of 75 km (47 mi).[10] That estimate for Vanth is in good agreement with the size of about 442.5 km (275.0 mi) derived from a stellar occultation in 2017.[30] Like Charon compared to Pluto, Vanth is quite large compared to Orcus, and is one reason for characterizing Orcus as the 'anti-Pluto'. If Orcus is a dwarf planet, Vanth would be the third-largest known dwarf-planet moon, after Charon and Dysnomia. The ratio of masses of Orcus and Vanth is uncertain, possibly anywhere from 1:33 to 1:12.[42] See alsoNotesReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to 90482 Orcus.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||