|

Maeshowe

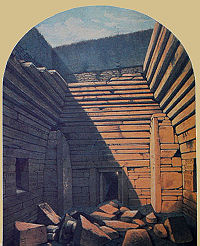

Maeshowe (or Maes Howe; Old Norse: Orkhaugr)[1] is a Neolithic chambered cairn and passage grave situated on Mainland Orkney, Scotland. It was probably built around 2800 BC. In the archaeology of Scotland, it gives its name to the Maeshowe type of chambered cairn, which is limited to Orkney. Maeshowe is a significant example of Neolithic craftsmanship and is, in the words of the archaeologist Stuart Piggott, "a superlative monument that by its originality of execution is lifted out of its class into a unique position."[2] Maeshowe is designated a scheduled monument[3] and part of the "Heart of Neolithic Orkney", a group of sites including Skara Brae designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999. Design and constructionMaeshowe is one of the largest tombs in Orkney; the mound encasing the tomb is 115 feet (35 m) in diameter and rises to a height of 24 feet (7.3 m).[4] Surrounding the mound, at a distance of 50 feet (15 m) to 70 feet (21 m) is a ditch up to 45 feet (14 m) wide. The grass mound hides a complex of passages and chambers built of carefully crafted slabs of flagstone weighing up to 30 tons.[5] It is aligned so that the rear wall of its central chamber[6] is illuminated on the winter solstice.[7] A similar display occurs in Newgrange.  This entrance passage is 36 feet (11 m) long and leads to the central almost square chamber measuring about 15 feet (4.6 m) on each side.[8] The current height of the chamber is 12.5 feet (3.8 m), this reflects the height to which the original stonework is preserved and capped by a modern corbelled roof. The original roof may have risen to a height of 15 feet (4.6 m) or more.[9] The entrance passage is only about 3 feet (0.91 m) high, requiring visitors to stoop or crawl into the central chamber. That chamber is constructed largely of flat slabs of stone, many of which traverse nearly the entire length of the walls. In each corner lie huge angled buttresses that rise to the vaulting. At a height of about 3 feet (0.91 m), the wall's construction changes from the use of flat to overlapping slabs creating a beehive-shaped vault.[10] Estimates of the amount of effort required to build Maeshowe vary; a commonly suggested number is 39,000 man-hours,[11][12] although Colin Renfrew calculated that at least 100,000 hours would be required.[13] Dating of the construction of Maeshowe is difficult but dates derived from burials in similar tombs cluster around 3000 BC. Since Maeshowe is the largest and most sophisticated example of the Maeshowe "type" of tomb, archaeologists have suggested that it is the last of its class, built around 2800 BC.[14] The people who built Maeshowe were users of grooved ware,[15] a distinctive type of pottery that spread throughout the British Isles from about 3000 BC. SitingMaeshowe appears as a grassy mound rising from a flat plain near the southeast end of the Loch of Harray. The land around Maeshowe at its construction probably looked much as it does today: Treeless, with grasses representative of ‘pollen assemblage zone’ MNH-I, reflecting "mixed agricultural practices, probably with a pastoral bias – there is a substantial amount of ribwort pollen, but also that of cereals."[16] Maeshowe is aligned with some other Neolithic sites in the vicinity, for example, the entrance of "Structure 8" of the nearby Barnhouse Settlement directly faces the mound. In addition, the so-called "Barnhouse Stone" in a field around 700 metres away is perfectly aligned with the entrance to Maeshowe. This entrance corridor is so placed that it lets the direct light of the setting sun into the chamber for a few days on each side of the winter solstice, illuminating the entrance to the back cell.[17]: 47 A Neolithic "low road" connects Maeshowe with the magnificently preserved village of Skara Brae, passing near the Standing Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar.[18] Low roads connect Neolithic ceremonial sites throughout Britain. Some archeologists believe that Maeshowe was originally surrounded by a large stone circle.[5] The complex including Maeshowe, the Ring of Brodgar, the Standing Stones of Stenness, Skara Brae, as well as other tombs and standing stones represents a concentration of Neolithic sites that is rivalled in Britain only by the complexes associated with Stonehenge and Avebury.[19] Visitor CentreThe Maeshowe Heart of Neolithic Orkney Visitor Centre is located in Stenness Village, and opened to the public in April 2017. The previous visitor centre for Maeshowe had been located in Tormiston Mill, which sits adjacent to the tomb. Tormiston Mill Visitor Centre closed in September 2016, for various reasons, notably the small carpark and dangerous road, along with lack of wheelchair access and asbestos. Tours depart from the Maeshowe Heart of Neolithic Orkney Visitor Centre on a shuttle bus which takes tour groups of 16 people down to the chambered cairn itself between 4 and 7 times a day. It contains an exhibition, a gift shop and public toilets, as well as staff facilities. StyleThe tomb gives its name to the Maeshowe type of Scottish chambered cairn, which is limited to Orkney.[20] Maeshowe is very similar to the famous Newgrange tomb in Ireland, suggesting a linkage between the two cultures.[21] Chambered tombs of the Maeshowe "type" are characterized by a long, low entrance passageway leading to a square or rectangular chamber from which there is access to a number of side cells. Although there are disagreements as to the attribution of tombs to tomb types, there are only seven definitely known Maeshowe-type tombs.[22] On Mainland, there are, in addition to Maeshowe; the tombs of Cuween Hill, Wideford Hill, and Quanterness. The tomb of Quoyness is found on Sanday, while Vinquoy Hill is located on Eday. Finally, there is an unnamed tomb on the Holm of Papa Westray. Anna Ritchie reports that there are three more Maeshowe-type tombs in Orkney but she doesn't name or locate them.[23] According to the description herein, a chambered tomb is normally characterized by grave goods, which were found at Cuween Hill and the tomb on Holm of Papa Westray (see the paragraph above) but were not found at Maeshowe. Further, the description of a passage grave states:

A potential explanation for the extraordinary genius of Maeshowe engineering and the lack of human remains was described by Peter Tompkins in 1971, who compared the structure at "Maes-Howe" to the Great Pyramid[25] suggesting the site was used as an observatory, calendar, and for May Day ceremonies rather than as a tomb. Tompkins extensively studied numerous documents related to the measurement and exploration of the Great Pyramid of Giza. He stated the central "observation chamber"[26] at Maeshowe was "corbeled like the Great Pyramid's Grand Gallery", was carefully leveled, plumbed", and the jointing is of a quality that "rivals that of the Great Pyramid". Rather than chambers of a tomb, Tompkins suggested the structure contained small "retiring rooms for the observers".[26] He suggested the entrance was very similar to Egyptian pyramids in that it had a "54 foot observation passage aimed like a telescope at a megalithic stone [2772 feet away] to indicate the summer solstice" (p. 130) in addition to its "Watchstone" to the West that indicated the equinoxes. The "sighting passage"[27] points to a northern star like the pyramids of Saqqara, Dashur and Medûm. Tompkins stated that "The similarity [of the pyramids] to the structure at Maes-Howe is indeed amazing".[27] He cited Professor Alexander Thom, former Chair of Engineering Science at Oxford, as writing about the geometry of construction and astronomical alignment of Maeshowe in this context in 1967.[28] Tompkins, citing Thom[citation needed] and others, described in detail how Maeshowe, Silbury Hill[29] and other ancient mounds and Neolithic megaliths across Britain served as extremely accurate observatories, calendars, and straight-line beacons for travelers, as well as how they were used ceremonially in May Day celebrations more than 4000 years ago. Excavation The "modern" opening of the tomb in July 1861 was by James Farrer, an antiquarian and the Member of Parliament (MP) for South Durham.[30] Farrer, like many antiquarians of the day, was not noted for his careful excavation of sites. John Hedges describes him as possessing "a rapacious appetite for excavation matched only by his crude techniques, lack of inspiration, and general inability to publish."[31] Farrer and his workmen broke through the roof of the entrance passage and found it filled with debris. He then turned his attention to the top of the mound, broke through, and over a period of a few days, emptied the main chamber of material that had filled it completely. He and his workmen discovered the famous runic inscriptions carved on the walls, proof that Norsemen had broken into the tomb at least six centuries earlier.[32] As described in the Orkneyinga saga, Maeshowe was looted by the famous Vikings Earl Harald Maddadarson and Ragnvald, Earl of Møre[1] in about the 12th century. The more than thirty runic inscriptions on the walls of the chamber represent the largest single collection of such carvings in the world. More recent fieldwork has demonstrated that the application of a computational photography technique, reflectance transformation imaging (RTI),[a] can shed light onto the nature of the inscriptions and their sequencing.[33]  Excavations have revealed that the external wall surrounding the ditch was rebuilt in the 9th century. Some archaeologists see this as evidence that the tomb may have been reused by the Norse people and that they were the source of the "treasure" found by the later looters.[17]: 46 ToponymyThe etymological genesis of the name Maeshowe is uncertain. The name may involve Gaelic mas, meaning 'a buttock'; in reference to a hillock.[34] However, Celtic-derived toponyms are uncommon in the Northern Isles,[34] and derivation from an analog of Welsh maes, 'an area of activity', is a doubtful proposition.[34] A Masshowe on Holm suggests an etymological parallel.[34] World Heritage statusThe "Heart of Neolithic Orkney" was listed as a World Heritage site in December 1999. In addition to Maeshowe, the site includes Skara Brae, the Standing Stones of Stenness, the Ring of Brodgar and other nearby sites. It is managed by Historic Environment Scotland, whose Statement of Significance for the site begins:

See also

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Maeshowe.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||