|

Large Ultraviolet Optical Infrared Surveyor

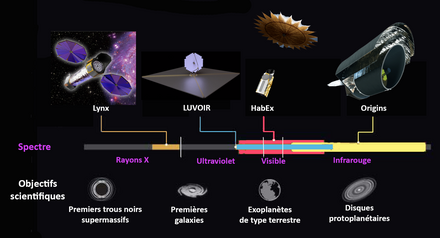

The Large Ultraviolet Optical Infrared Surveyor, commonly known as LUVOIR (/luːˈvwɑːr/), is a multi-wavelength space telescope concept being developed by NASA under the leadership of a Science and Technology Definition Team. It is one of four large astrophysics space mission concepts studied in preparation for the National Academy of Sciences 2020 Astronomy and Astrophysics Decadal Survey.[2][3] While LUVOIR is a concept for a general-purpose observatory, it has the key science goal of characterizing a wide range of exoplanets, including those that might be habitable. An additional goal is to enable a broad range of astrophysics, from the reionization epoch, through galaxy formation and evolution, to star and planet formation. Powerful imaging and spectroscopy observations of Solar System bodies would also be possible. LUVOIR would be a Large Strategic Science Mission and was considered for a development start sometime in the 2020s. The LUVOIR Study Team, under Study Scientist Aki Roberge, has produced designs for two variants of LUVOIR: one with a 15.1 m diameter telescope mirror (LUVOIR-A) and one with an 8 m diameter mirror (LUVOIR-B).[4] LUVOIR would be able to observe ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths of light. The Final Report on the 5-year LUVOIR mission concept study was publicly released on 26 August 2019.[5] On 4 November 2021, the 2020 Astrophysics Decadal Survey recommended development of a "large (~6 m aperture) infrared/optical/ultraviolet (IR/O/UV) space telescope", with the science goals of searching for signatures of life on planets outside of the solar system and enabling a wide range of transformative astrophysics. Such a mission draws upon both the LUVOIR and HabEx mission concepts.[6][7][8] BackgroundIn 2016, NASA began considering four different space telescope concepts for future Large Strategic Science Missions.[9] They are the Habitable Exoplanet Imaging Mission (HabEx), Large Ultraviolet Optical Infrared Surveyor (LUVOIR), Lynx X-ray Observatory (lynx), and Origins Space Telescope (OST). In 2019, the four teams turned in their final reports to the National Academy of Sciences, whose independent Decadal survey committee advises NASA on which mission should take top priority. If funded, LUVOIR would launch in approximately 2039 using a heavy launch vehicle, and it would be placed in an orbit around the Sun–Earth Lagrange point 2.[5] Mission LUVOIR's main goals are to investigate exoplanets, cosmic origins, and the Solar System.[4] LUVOIR would be able to analyze the structure and composition of exoplanet atmospheres and surfaces. It could also detect biosignatures arising from life in the atmosphere of a distant exoplanet.[10] Atmospheric biosignatures of interest include CO The scope of astrophysics investigations include explorations of cosmic structure in the far reaches of space and time, formation and evolution of galaxies, and the birth of stars and planetary systems. In the area of Solar System studies, LUVOIR can provide up to about 25 km imaging resolution in visible light at Jupiter, permitting detailed monitoring of atmospheric dynamics in Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune over long timescales. Sensitive, high resolution imaging and spectroscopy of Solar System comets, asteroids, moons, and Kuiper Belt objects that will not be visited by spacecraft in the foreseeable future can provide vital information on the processes that formed the Solar System ages ago. Furthermore, LUVOIR has an important role to play by studying plumes from the ocean moons of the outer Solar System, in particular Europa and Enceladus, over long timescales. Design LUVOIR would be equipped with an internal coronagraph instrument, called ECLIPS for Extreme Coronagraph for LIving Planetary Systems, to enable direct observations of Earth-like exoplanets. An external starshade is also an option for the smaller LUVOIR design (LUVOIR-B). Other candidate science instruments studied are: High-Definition Imager (HDI), a wide-field near-UV, optical, and near-infrared camera; LUMOS, a LUVOIR Ultraviolet Multi-Object Spectrograph; and POLLUX, an ultraviolet spectropolarimeter. POLLUX (high-resolution UV spectropolarimeter) is being studied by a European consortium, with leadership and support from the CNES, France. The observatory can observe wavelengths of light from the far-ultraviolet to the near-infrared. To enable the extreme wavefront stability needed for coronagraphic observations of Earth-like exoplanets,[11] the LUVOIR design incorporates three principles. First, vibrations and mechanical disturbances throughout the observatory are minimized. Second, the telescope and coronagraph both incorporate several layers of wavefront control through active optics. Third, the telescope is actively heated to a precise 270 K (−3 °C; 26 °F) to control thermal disturbances. The LUVOIR technology development plan is supported with funding from NASA's Astrophysics Strategic Mission Concept Studies program, the Goddard Space Flight Center, the Marshall Space Flight Center, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and related programs at Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems and Ball Aerospace. LUVOIR-ALUVOIR-A, previously known as the High Definition Space Telescope (HDST), was proposed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) on 6 July 2015.[12] It would be composed of 36 mirror segments with an aperture of 15.1 metres (50 ft) in diameter, offering images up to 24 times sharper than the Hubble Space Telescope.[13] LUVOIR-A would be large enough to find and study the dozens of Earthlike planets in our nearby neighborhood. It could resolve objects such as the nucleus of a small galaxy or a gas cloud on the way to collapsing into a star and planets.[12] The case for HDST was made in a report entitled "From Cosmic Birth to Living Earths", on the future of astronomy commissioned by AURA, which runs the Hubble and other observatories on behalf of NASA and the National Science Foundation.[14] Ideas for the original HDST proposal included an internal coronagraph, a disk that blocks light from the central star, making a dim planet more visible, and a starshade that would float kilometers out in front of it to perform the same function.[15] LUVOIR-A folds so it only needs an 8-metre wide payload fairing.[5] Initial cost estimates are approximately US$10 billion,[15] with lifetime cost estimates of $18 billion to $24 billion.[1] LUVOIR-BLUVOIR-B, previously known as the Advanced Technology Large-Aperture Space Telescope (ATLAST),[16][17][18][19] is an 8 meter architecture initially developed by the Space Telescope Science Institute,[20] the science operations center for the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). While smaller than LUVOIR-A, it is being designed to produce an angular resolution that is 5–10 times better than the JWST, and a sensitivity limit that is up to 2,000 times better than HST.[16][17][20] The LUVOIR Study Team expects that the telescope would be able to be serviced – similar to HST – either by an uncrewed spacecraft or by astronauts via Orion or Starship. Instruments such as cameras could potentially be replaced and returned to Earth for analysis of their components and future upgrades.[19] The original backronym used for the initial mission concept, "ATLAST", was a pun referring to the time taken to decide on a successor for HST. ATLAST itself had three different proposed architectures – an 8 metres (26 ft) monolithic mirror telescope, a 16.8 metres (55 ft) segmented mirror telescope, and a 9.2 metres (30 ft) segmented mirror telescope. The current LUVOIR-B architecture adopts JWST design heritage, essentially being an incrementally larger variant of the JWST, which has a 6.5 m segmented main mirror. Running on solar power, it would use an internal coronagraph or an external occulter which can characterize the atmosphere and surface of an Earth-sized exoplanet in the habitable zone of long-lived stars at distances up to 140 light-years (43 pc), including its rotation rate, climate, and habitability. The telescope would also allow researchers to glean information on the nature of the dominant surface features, changes in cloud cover and climate, and, potentially, seasonal variations in surface vegetation.[21] LUVOIR-B was designed to launch on a heavy-lift rocket with an industry-standard 5 metres (16 ft) diameter launch fairing. Lifetime cost estimates range from $12 billion to $18 billion.[1] See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||