|

Jasperware

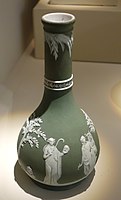

Jasperware, or jasper ware, is a type of pottery first developed by Josiah Wedgwood in the 1770s. Usually described as stoneware,[2] it has an unglazed matte "biscuit" finish and is produced in a number of different colours, of which the most common and best known is a pale blue that has become known as "Wedgwood blue". Relief decorations in contrasting colours (typically in white but also in other colours) are characteristic of jasperware, giving a cameo effect. The reliefs are produced in moulds and applied to the ware as sprigs.[3] After several years of experiments, Wedgwood began to sell jasperware in the late 1770s, at first as small objects, but from the 1780s adding large vases. It was extremely popular, and after a few years many other potters devised their own versions. Wedgwood continues to make it into the 21st century. The decoration was initially in the fashionable Neoclassical style, which was often used in the following centuries, but it could be made to suit other styles. Wedgwood turned to leading artists outside the usual world of Staffordshire pottery for designs. High-quality portraits, mostly in profile, of leading personalities of the day were a popular type of object, matching the fashion for paper-cut silhouettes. The wares have been made into a great variety of decorative objects, but not typically as tableware or teaware. Three-dimensional figures are normally found only as part of a larger piece, and are typically in white. Teawares are usually glazed on the inside.[4]  In the original formulation the mixture of clay and other ingredients is tinted throughout by adding dye (often described as "stained"); later the formed but unfired body was merely covered with a dyed slip, so that only the body near the surface had the colour. These types are known as "solid" and "dipped" (or "Jasper dip") respectively. The undyed body was white when fired, sometimes with a yellowish tinge; cobalt was added to elements that were to stay white.[5] Jasperware composition and colours Named after the mineral jasper for marketing reasons, the exact Wedgwood formula remains confidential, but analyses indicate that barium sulphate is a key ingredient.[6] Wedgwood had introduced a different type of stoneware called black basalt a decade earlier. He had been researching a white stoneware for some time, creating a body called "waxen white jasper" by 1773–1774. This tended to fail in firing, and was not as attractive as the final jasperware, and little was sold.[7] Jasperware's composition varies but according to one 19th-century analysis it was approximately: 57% barium sulphate, 29% ball clay, 10% flint, 4% barium carbonate. Barium sulphate ("cawk" or "heavy-spar") was a fluxing agent and obtainable as a by-product of lead mining in nearby Derbyshire.[8] The fired body is naturally white but usually stained with metallic oxide colors; its most common shade is pale blue, but dark blue, lilac, sage green (described as "sea-green" by Wedgwood),[9] black, and yellow are also used, with sage green due to chromium oxide, blue to cobalt oxide, and lilac to manganese oxide, with yellow probably coming from a salt of antimony, and black from iron oxide.[10][11] Other colours sometimes appear, including white used as the main body colour, with applied reliefs in one of the other colours. The yellow is rare. A few pieces, mostly the larger ones like vases, use several colours together,[12] and some pieces mix jasperware and other types together. The earliest jasper was stained throughout, which is known as "solid," but before long most items were coloured only on the surface; these are known as "dipped" or "dip". Dipping was first used in 1777, Wedgwood writing that "the Cobalt @ 36s. per lb, which being too dear to mix with the clay of the whole grounds".[13] By 1829 production in jasper had virtually ceased, but in 1844 production resumed making dipped wares. Solid jasper was not manufactured again until 1860.[14] Early dark blue was often made by dipping a body made from the solid light blue. In the best early pieces the relief work was gone over, including some undercutting, by lapidaries.[12] Wedgwood colours

Wedgwood designs The artists used for jasperware cannot always be identified, as they are not named on pieces they designed.[12] Wedgwood commissioned George Stubbs and William Wood, as well as the Flaxmans, father and son. William Hackwood was his chief in-house modeller, who was sometimes allowed to initial pieces.[15] Using the celebrity of aristocratic amateurs Lady Templeton and Lady Diana Beauclerk, as well as Emma Crewe, no doubt helped sales.[16] Ancient and modern works in various media were copied and new, original designs created. Jasperware is particularly associated with the neoclassical sculptor and designer John Flaxman Jr., who began to supply Wedgwood with designs from 1775. Flaxman mostly worked in wax when designing for Wedgwood.[17] The designs were then cast; some of them are still in production. Sir William Hamilton's collection of ancient Greek vases was an important influence on Flaxman's work. These vases were first known in England from D'Hancarville's engravings, published in stages from 1766.[17] Inspiration for Flaxman and Wedgwood came not only from ancient ceramics, but also from cameo glass, particularly the Portland Vase which was brought to England by Hamilton by 1784. The vase was lent to Wedgwood by William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland from 1786. Wedgwood devoted four years of painstaking attempts at duplicating the vase in black and white jasperware, which was finally completed in 1790, the figures perhaps modelled by William Hackwood. The replica was exhibited in London in that year, with the initial showing restricted to 1,900 tickets, which soon sold out. Wedgwood's careful copies proved extremely useful when the vase was smashed in the British Museum in 1845, and then reconstructed by the restorer John Doubleday. The original edition was of 50 copies; in 1838 a further edition was cast in one piece, with the background then painted.[18]

Date markings Wedgwood jasperware can often be dated by the style of potter's marks, although there are exceptions to the rules:

Other jasperwareJasperware was widely copied in England and elsewhere from its introduction, especially by other makers of Staffordshire pottery.[20] The Real Fabrica del Buen Retiro in Madrid produced jasperware effects in biscuit porcelain. At the end of the 18th century, they made jasperware plaques for a "porcelain room" in the Casita del Príncipe at the Escorial.[21] In the late 19th century, Jean-Baptiste Stahl developed his own style and techniques during his work at Villeroy & Boch in Mettlach, Saar, Germany. The name Phanolith was coined for this kind of jasperware. His work is praised for the translucency of the white porcelain on a colored background. Stahl's work is known for its refined modelling and the vibrancy of its figures. He thus combined the benefits of jasperware and pâte-sur-pâte. A stand at the World's Fair 1900 in Paris was the first major public presentation of his work and gained him a gold medal. For this event, two huge wall plates were created with dimensions of 220 cm × 60 cm (87 in × 24 in), each.[citation needed]

References

Sources

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Jasperware. |