|

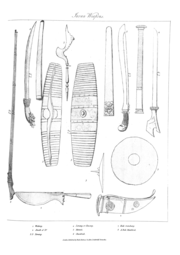

Istinggar Istinggar is a type of matchlock firearm built by the various ethnic groups of the Maritime Southeast Asia. The firearm is a result of Portuguese influence on local weaponry after the capture of Malacca (1511).[1]: 380, 388–389 Before this type of gun, in the archipelago already existed early long gun called bedil, or Java arquebus as the Chinese call it. Most of the specimens in the Malay Peninsula are actually Malaysian in origin, manufactured in the Langkasuka lands of Kedah. The states of the Malay Peninsula imported this firearm as it was widely used in their wars.[2]: 57 [3]: 2–3 EtymologyThe name istinggar comes from the Portuguese word espingarda meaning arquebus or firearm. This term then corrupted into estingarda, eventually to setinggar or istinggar.[4]: 193 [2]: 53 [5]: 64 The word has many variations in the archipelago, such as satinggar, satenggar, istenggara, astengger, altanggar, astinggal, ispinggar, and tinggar.[6][7][8][9][10][11]: 209 [12] HistoryThe predecessor of firearms, the pole gun (bedil tombak), was recorded as being used by Java in 1413.[13][14]: 245 However, the knowledge of making "true" firearms in the archipelago came after the middle of the 15th century. It was brought by the Islamic nations of West Asia, most probably the Arabs. The precise year of introduction is unknown, but it may be safely concluded to be no earlier than 1460.[15]: 23 Before the arrival of the Portuguese in Southeast Asia, the Malays already possessed early firearms, the Java arquebus.[16] This firearm has a very long barrel (up to 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) in length), and during the Portuguese conquest of Malacca (1511), it is proven to be able to penetrate a ship's hull to the other side.[17][15]: 22 However the lock mechanism and the barrel of the gun are very crude.[16][18]: 53 The Portuguese in Goa independently produced their own matchlock firearms. Starting in 1513, the tradition of German-Bohemian gun-making was merged with Turkish gun-making traditions.[19]: 39–41 This resulted in the Indo-Portuguese tradition of matchlocks. Indian craftsmen modified the design by introducing a very short, almost pistol-like buttstock held against the cheek, not the shoulder, when aiming. They also reduced the caliber and made the gun lighter and more balanced. This was a hit with the Portuguese who did a lot of fighting aboard ship and on river craft, and valued a more compact gun.[19]: 41 [20] Javanese snap matchlock mechanism, made of cast brass. Afonso de Albuquerque compared Malaccan gun founders as being on the same level as those of Germany. However, he did not state what ethnicity the Malaccan gun founder was.[21]: 128 [22]: 221 [23]: 4 Duarte Barbosa stated that the arquebus-maker of Malacca was Javanese.[24]: 69 The Javanese also manufactured their own cannon in Malacca.[25] Anthony Reid argued that the Javanese handled much of the productive work in Malacca before 1511 and in 17th century Pattani.[24]: 69 Wan Mohd Dasuki Wan Hasbullah explained several facts about the existence of gunpowder weapons in Malacca before its fall in 1511:[26]: 97–98

There were 2 different lock mechanisms used in Indo-Portuguese guns. One has a single leaf mainspring of the Lusitanian gun prototypes, which can be found in Ceylon, Malay peninsula, Sumatra, and Vietnam, and the other has a V-shaped mainspring, which can be found in Java, Bali, China, Japan, and Korea.[19]: 103–104 [27] The lock mechanism of istinggar is usually made of brass.[28]: 99 The Malays used bamboo covers in their matchlock arquebus barrel and bound them with rattan, to keep them dry in wet weather.[28]: 100 [29]: 53 Istinggar is typically longer than Japanese guns. The absence of a channel for the ramrod indicated that they were used resting on a wall or used from a ship's railing like the lela or rentaka. In this case, the ramrod did not need a compartment.[30] The Malays also made small mallets to drive the musket balls down the barrel.[28]: 99–100 Minangkabau people of interior Sumatra are renowned for their manufacture of gunpowder-based weapons. Contemporary records of João de Barros (1496–1570) indicated that before the arrival of European people, the Sumatrans had not used firearms.[23]: 3 Iron and steel were produced in their forges, but by the 19th century, they became more reliant on the Europeans.[31]: 347 The matchlock arquebus of Minangkabau was dubbed "Istenggara Menangkabowe" (or istinggar Minangkabau, or simply satingga).[11]: 209 [5]: 64 [32]: 277 The production was enough to fulfill local needs, the Minangkabau also exported their firearms to other areas, such as Aceh, Malacca, and Siak Sultanate.[31]: 347 [33] The barrels are made by rolling a flatted bar of iron of proportionate dimensions spirally around a circular rod, and beating it till the parts of the former unite, and the art of boring is probably unknown to them.[31]: 347–348 This manufacture continued even into the 19th century when matchlock has already been obsolete.[2]: 54 [33] A manuscript called Ilmu Bedil (means "knowledge of firearm") is a treatise about this type of istinggar. The Minangkabau also produced other firearms, the terakul (dragoon pistol).[5]: 61 The Batak people used matchlock guns with locks made of copper and were regarded by Marsden as expert marksmen. However, the guns of Batak were supplied by Minangkabau traders.[31]: 377–378 The Makassar people of the Kingdom of Gowa, which maintained friendly relationships with the Portuguese since 1528,[34]: 372 benefitted considerably from Portuguese assistance in building up its military strength. Converted to Islam in the early 1600s, they made holy war (jihad) on its nonbeliever neighbor, the Bugis.[35]: 431 The Makassan were already manufacturing muskets, probably from Portuguese espingarda, sometime in the late 16th or early 17th century. By the 18th century, European people praised the guns produced by their Bugis neighbor, which has a straight bore and fine inlay work.[35]: 384 During years of warfare, Bugis and Makassarese soldiers, dressed in waju rante (chain mail) and muskets which they made themselves.[35]: 384 Between 1603 and 1606, the Iberian Union troops attacked Ternate twice and reported muskets and arquebuses were used by the "Moros" (i.e. Moors, or Muslims).[36] Nicolas Gervaise notes that in Makassar "There are no people in East Indies more nimble in getting on horseback, to draw a bow, to discharge a fuzil (musket), or to point a cannon (than the Makassarese)".[37]: 70  Eventually, the Istinggar spread to the Muslim-controlled areas of the Philippine archipelago, where it was known as "astinggal". The 1613 San Buenaventura Tagalog dictionary defines "astingal" as "arquebus, of the kind they used to use in olden times in their wars and which came from Borneo". This appears to be the first reference to them in northern Luzon.[38]: 177 Despite this, the Spaniards never faced any in their encounters in Luzon as they did in Mindanao.[39] In 1609, the Spaniards reported that in Zambales many of the natives handle the arquebuses and muskets quite skilfully, since they have seen the Spaniards use their weapons.[36] The Hindu inhabitants of Bali and Lombok, being the remnant of Majapahit hindus,[40] are famous for their manufacture of the matchlock. In the 1800s Alfred Wallace saw two guns of their manufacture, 6–7 ft (1.8–2.1 m) long, with a proportionately large bore. The wooden stock is well made, extended to the front end of the barrel. The barrels were twisted and finished, with silver and gold ornament.[20]: 98 For making the long barrel, the natives use 18 in (460 mm) pieces of barrel which are first bored small, and then welded together upon a straight iron rod. The whole barrel is then worked with borers of gradually increasing size, and in three days the boring is finished.[41]: 170 For firearms using flintlock mechanism, the inhabitants of the Nusantara archipelago are reliant on Western powers, as no local smith could produce such complex components.[42]: cxli [20]: 98 [43]: 42 and 50 These flintlock firearms are completely different weapons and were known by another name, senapan or senapang, from the Dutch word snappaan.[15]: 22 The gun-making areas of Nusantara could make these senapan; the barrel and the wooden part is made locally, but the mechanism is imported from the European traders.[43]: 42 and 50 [5]: 65 [20]: 98 The Javanese was among the earliest to modernize: After the VOC began replacing matchlocks with flintlocks in the 1680s, the Javanese already requested them by 1690s. Flintlock senapan began to appear in the Javanese arsenal in early 1700 AD.[18]: 55–56 Gallery

See alsoWikimedia Commons has media related to Istinggar.

References

|